Each year on April 22nd, people and nations around the world celebrate Earth Day to raise awareness and promote action toward environmental protection and sustainability. Activities typically include community clean-ups and educational campaigns designed to promote sustainability in daily life.

The origins of Earth Day date back to the 1960s and a decade of growing enviro-consciousness brought about by the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and a series of environmental disasters that climaxed with a devastating oil spill off the coast of California in 1969. Gaylord Nelson, a U.S. Senator from Wisconsin, organized the first Earth Day in 1970, when an estimated 20 million Americans took part in organized activities ranging from tree plantings to beach cleanups and teach-ins on college campuses.

Since those humble beginnings, Earth Day has become a global event – but amidst the tree plantings and landscape revitalization lies a subtle and yet direct connection between Earth Day and Public Health. Just as we depend on the natural environment for our survival, civilization creates and shapes a social and economic environment that greatly influences the health and well-being of our species.

In short, we are part of the earth, too.

Creeds and Connections

Throughout history, many societies and cultures have centered around philosophies that proclaim our interconnectedness with the earth and other living beings. Indigenous peoples of America, New Zealand, and Australia maintain a deep connection with the earth and consider themselves a part of it. In Hinduism, the earth is viewed as a goddess, and humans are seen as her children. Taoism puts forth the idea that everything in the universe is interconnected and emphasizes living in harmony with the natural world. In Buddhism, the earth is viewed as a living organism, and humans are seen as one small part of the larger ecosystem.

So, when we celebrate Earth Day, it stands to reason we should consider how well we are progressing in protecting humanity as well as the earth’s environmental state. As a benchmark, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer insights into our progress.

World Health Organization

Improving Public Health is one of the key objectives of the SDGs, which are a set of 17 goals adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2015 with the aim of promoting sustainable development and addressing some of the world’s most pressing social, economic, and environmental challenges. With an eye toward 2030, the SDGs explicitly recognize the importance of promoting environmental sustainability while also considering the interdependence of environmental, social, and economic factors. Achieving these goals requires concerted efforts from governments, civil society, and the private sector.

One of the goals, SDG 3, specifically focuses on ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all humans at all ages. It includes a range of subgoals and targets related to improving access to healthcare, reducing maternal and child mortality, combating communicable diseases, and addressing non-communicable diseases such as cancer and diabetes. Still other SDGs, such as those related to poverty reduction, gender equality, clean water and sanitation, and sustainable cities and communities, also have a significant impact on public health outcomes.

The theme for Earth Day 2023 is “Invest in the Planet.” Using SDG 3 as a baseline, we can take an inventory of the progress and determine how much further is needed to go toward investing in human potential.

SDG 3.1 Reducing Maternal Mortality

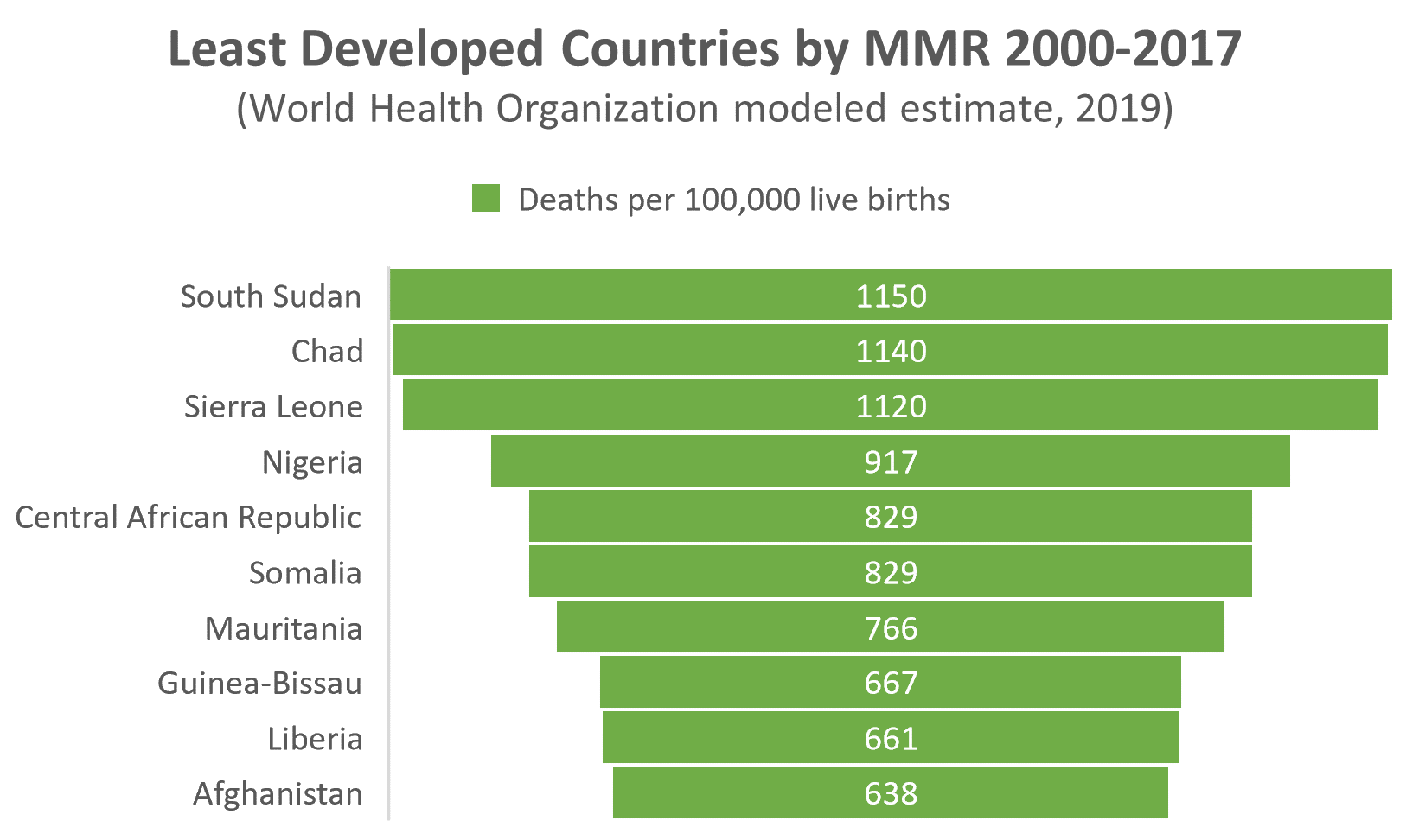

SDG 3.1 calls for reduction of the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to less than 70 deaths by 2030. MMR is calculated as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. According to UN inter-agency estimates, the global MMR declined by 34 percent – from 342 deaths to 223 deaths, between 2000 and 2020.1 This translates to approximately 295,000 maternal deaths worldwide each year.

While progress is being made in this area, the current MMR is still three times higher than the goal. Moreover, progress remains uneven across regions and countries. Progress has also stalled over the past several years, as the global MMR has only improved by a fraction of a percentage since 2016. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have the highest maternal mortality rates among all regions, with an estimated 533 and 215 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, respectively, in 2017.2 By contrast, the maternal mortality ratio in high-income countries was only 11 deaths per 100,000 live births in the same year.

Reducing the maternal mortality rate is important for several reasons. First and foremost, maternal health is a human right — every woman should have access to safe, effective, and timely healthcare during pregnancy and childbirth. It follows that preventable maternal deaths (which constitute about 80% of all maternal deaths) represent an ongoing failure of global health systems to provide adequate care.

Reducing maternal mortality is also the first step toward achieving broader global health and SDG goals. Maternal health is closely linked to child health, and improving maternal outcomes can have a positive impact on child survival and health. By taking a cue from Earth Day 2023, investing in maternal health can have broader, interrelated social and economic benefits, such as reducing poverty and promoting economic growth while also promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment.

Data demonstrates that reductions in maternal mortality are achievable through evidence-based interventions, such as improving access to skilled birth attendants, ensuring timely access to emergency obstetric care, promoting family planning and reproductive health services, and addressing underlying social and economic determinants of maternal health. Nepal is often put forth as an example of what can be accomplished when such investments are made.

The Nepal Demographic & Health Survey shows that Nepal’s MMR declined from 539 in 2000 to 239 in 2016, a 56% reduction in the MMR. Nepal achieved these improvements through a range of interventions, such as making significant investments in training and deploying skilled birth attendants in rural areas, where maternal mortality rates are typically higher. According to the World Bank, births attended by skilled health personnel in Nepal increased from about 9% in 2000 to 58% in 2017.

Nepal has also worked to improve access to emergency obstetric care, such as cesarean sections and blood transfusions, which can be lifesaving in cases of obstetric emergencies. For example, Nepal has implemented a community-based health care program that has established birthing centers in remote areas and linked them with higher-level facilities to provide emergency obstetric care when needed. Nepal has also worked to address underlying social and economic determinants of maternal health, such as poverty, gender inequality, and lack of education.3 For example, Nepal has implemented a “cash transfer program” that provides financial incentives to families who send their daughters to school and encourages them to delay marriage and childbearing.

Ethiopia is another country making significant progress in reducing its maternal mortality rate (MMR) in recent years. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Ethiopia’s MMR declined from 676 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2011 to 353 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2019, a 48% reduction in the MMR.

As in Nepal, Ethiopia has made significant investments in training and deploying skilled birth attendants in rural areas. According to a study published in the International Journal for Equity in Health, the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel in Ethiopia increased from 6% in 2000 to 28% in 2016.4 Ethiopia has also established maternal waiting homes and ambulance services to transport women to health facilities for emergency obstetric care as well as an implementation of a “health extension program” to train and deploy community health workers to provide essential maternal and child health services in rural areas.

From a practical perspective, successes in both Nepal and Ethiopia are predicated on a willingness to collaborate with international partners and civil society organizations in pursuit of these goals. Both countries have worked closely with the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and other partners to develop and implement maternal health programs while involving communities and families at the local level in efforts to improve maternal health outcomes.

Combating Communicable Diseases (SDG 3.3)

SDG 3.3, combatting communicable diseases, has proven incredibly challenging. The global incidence rate of communicable diseases has shown a mixed trend. While some have shown a decline in incidence over the past two decades, others have remained stable or increased.

During the past two decades there have been notable declines in incidence rates for such diseases as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. UNAID.org reports that new HIV infections declined by 32% between 2010 and 2021 – from 2.2 million to 1.5 million – while HIV-related deaths declined by 52% (1.35 million to 650,000) over the same period. Between 2000 and 2019, the global incidence rate of malaria declined by 29%, although that progress has plateaued since 2015 (see “Malaria’s Long Tail,” Public Health Landscape, October 2022). The incidence rate of tuberculosis also declined by 9% between 2015 and 2019.

That is the good news.

On the other hand, several important communicable diseases have been trending in the wrong direction. The number of dengue cases reported to WHO, for example, increased by more than ten-fold between 2000 and 2019, rising from 505,000 to 5.2 million. At the same time, the appearance of new, emerging, and re-emerging communicable diseases such as Ebola virus disease, Zika virus disease, and COVID-19, have all highlighted the significant and ongoing threat infectious diseases pose. ‘Investing in Our Planet’ must also include improved efforts and strategies to address these ongoing challenges. That means ensure that all people have access to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment services.

Source: CDC

Preventing and treating communicable diseases in low-income countries remains a chief concern. According to the WHO, infectious diseases account for almost half (approximately 45%) of deaths in low-income countries, compared to just 3% in high-income countries. This burden also has a significant, negative economic impact on low-income countries, through loss of productivity, increased healthcare costs, and reduced economic growth.

Communicable diseases do not respect borders and can easily spread beyond national boundaries. By investing to prevent and treat communicable diseases in low-income countries, the risk of outbreaks and pandemics with global health security implications is reduced. Social consequences, such as stigmatization and discrimination, can also be attributed to communicable disease incidence and socioeconomic disadvantage.

Examples of successful efforts to address communicable disease challenges include:

- Immunization programs: Immunization is a highly effective way to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, and many low-income countries have made significant progress in expanding access to immunization programs. The global vaccination coverage for measles eclipsed 85% in 2018, with the largest improvements occurring in Africa and Southeast Asia. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the number of global measles cases declined over roughly the same period from about 34 million cases in 2000 to 9.5 million cases in 2021, a 72 per cent reduction.5

- Community-based interventions: Community-based interventions, such as community health worker programs, also show to be highly effective in improving access to healthcare and preventing the spread of infectious diseases.

- Improved access to healthcare: As with efforts to reduce maternal mortality, improvement of access to healthcare, particularly in rural areas, can be especially effective in preventing and treating communicable diseases.

Brazil is often hailed as a country that has made notable progress in improving disease prevention outcomes in recent years. Infant mortality rate, which is a key indicator of overall health outcomes, declined from 18.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2010 to 12.4 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2019. This progress can be attributable to several initiatives spawned from a universal healthcare system (Unified Health System, or SUS) that Brazil adopted in 1988 to provide free healthcare to its citizens.

The SUS helps battle communicable diseases by ensuring people have access to preventive services, such as vaccinations and screening tests. Brazil also invests in disease surveillance and response systems, which are critical for detecting and responding to communicable disease outbreaks. In 1999, Brazil created The Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária – ANVISA) to oversee disease control measures as well as monitor the safety and efficacy of vaccines and other medical products.

Brazil’s Family Health Strategy (FHS) program, launched in 1994, deploys community health workers to provide health services in underserved areas and has been successful in reducing the incidence of communicable diseases and improving overall health outcomes. FHS brought about several improvements to the fabric of the Brazilian healthcare system, with residual positive effects in combatting communicable disease. These improvements include:

- legislating a full working week for primary care doctors

- expanding primary care residency programs

- enabling Community Healthcare Workers to become municipal employees

- increasing federal primary care funding by 110 percent from 2010 to 2015

- initiating the “More Doctors” program to recruit Brazilian and foreign doctors

- working to better integrate health and education at the federal level6

Moving eastward, Rwanda has also made significant progress toward SDG 3.3. According to the UN, the under-five mortality rate in Rwanda improved by more than 60 per cent in a span of just ten years, declining from 82 deaths per 1000 live births in 2010 to about 30 deaths per 1000 live births in 2019. This progress reflects a concerted effort by the Rwandan government to increase its investment in Public Health.

The incidence of malaria in Rwanda decreased by 70% between 2010 and 2018, achieved largely because of these investments. According to the Rwanda Health Sector Strategic Plan 2018-2024, these investments will continue. The Rwandan government’s health sector expenditure is projected to increase from 6.9% of GDP in 2017 to 8.2% of GDP by 2024 – substantial when compared to an average of 6% of GDP spent on healthcare across sub-Saharan Africa.

Specific investments include improving disease surveillance and response systems to detect and respond to outbreaks quickly. The improvements involve the establishment of community-based surveillance systems, laboratory networks, and the use of mobile technology to report disease cases in real-time. Rwanda has also implemented a comprehensive vaccination program that includes routine immunizations and targeted immunizations for specific populations, leading to high vaccination coverage rates, particularly for infant children.

Other efforts in Rwanda include foundational education and awareness campaigns to bring about behavioral changes that impact Public Health. These campaigns have focused on hand hygiene, safe food-handling practices, and the importance of seeking medical care when disease infection is suspected. To help establish and maintain these programs, Rwanda has collaborated with international organizations such as the WHO and the CDC. These partnerships have helped to build capacity, provide technical assistance, and mobilize resources to support Rwanda’s efforts.

Addressing Mental Health (SDG 3.4)

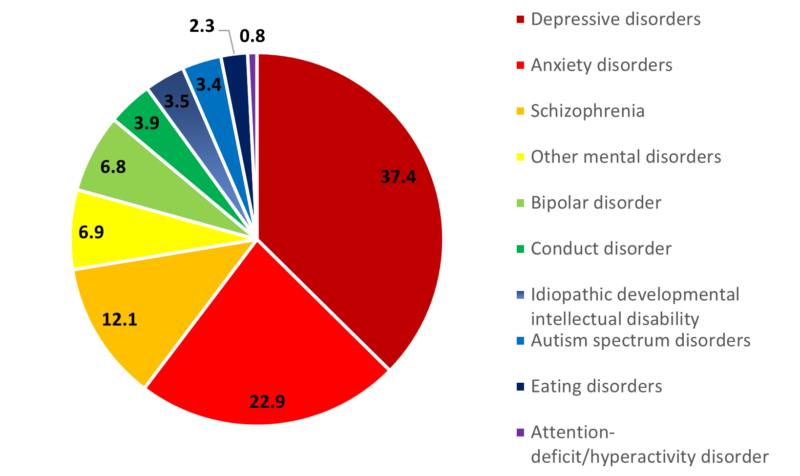

Mental health is the basis for its own important SDG subgoal, reinforcing the interconnectedness of body, mind, and environment. The global burden of mental health is typically quantified using various Public Health indicators such as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), years of life lost (YLL), and years lived with disability (YLD).7 Mental health disorders account for a significant portion of the global burden of disease, with depression being the leading cause of disability worldwide.

It is estimated that as many as 418 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) could be attributable to mental disorders in 2019 (16% of global DALYs). The economic value associated with this burden is estimated at about USD 5 trillion.8

Arias et al., T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, 2002

Several actions are needed to drive progress toward improved mental health. To begin with, there is a significant treatment gap for mental health disorders, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Improving access to mental health services, including prevention, early intervention, and treatment, is essential for addressing the global burden of mental health. Only by investing in mental health services and integrating mental health into primary healthcare systems, can progress be realized.

Stigma and discrimination associated with mental health have historically prevented people from seeking help and/or accessing treatment. Reversing these attitudes requires a multi-sectoral approach involving government, civil society, and local communities.9 As with other Public Health-related challenges, progress in mental health can be accelerated by public awareness, education, and advocacy campaigns.

(Both Sexes and All Ages)

Source: GDB 2017

Australia has achieved significant progress in improving mental health outcomes in recent years, both from a statistical and practical perspective. A national mental health strategy was first unveiled in Australia in 1992 and continues to thrive. Through interventions focused on promoting mental health and well-being, the country has seen a reduction in suicide rates as well as declining hospitalizations for mental health disorders.

In 2017, the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care launched its “Head to Health” program. Head to Health brings together apps, online programs, online forums, and phone services, as well as a range of digital information resources for Australians of all ages. In 2022, Australia’s National Mental Health Commission published its Vision 2030 for Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. The vision includes a range of initiatives, such as increased funding for mental health services, improved access to online mental health resources, and mental health training for healthcare professionals.

Scotland is another country that has made significant progress in improving mental health outcomes in recent years. Like Australia, Scotland developed a national mental health strategy which it first published in 2017. Scotland has also implemented community-based interventions aimed at promoting mental health and preventing mental health disorders. The Choose Life initiative, for example, is a national suicide prevention strategy that includes community-based interventions aimed at reducing suicide rates.

According to the National Records of Scotland, the suicide rate in Scotland has decreased from 13.3 deaths per 100,000 people in 2016 to 12.5 deaths per 100,000 people in 2019. The Information Services Division Scotland also reports that the number of antidepressant prescriptions rose to 6.6 million items dispensed in 2017/2018, as compared with 3.8 million items in 2007/2008 — an increase of 73.2%.10 While this may not establish a clear causal relationship, it seems likely that improved access to mental health services (and reduced stigma associated with mental health disorders) has led more Scottish to seek treatment to ensure mental health and well-being.

While some progress toward SDG 3.4 has been made at the global level, there remains a need for more research and innovation in the field of mental health – particularly in developing new and effective treatments for disorders. Not only will investments in research lead to the discovery of potential new interventions for mental health, it will also help to improve our understanding of mental health disorders to inform both policy and practice.

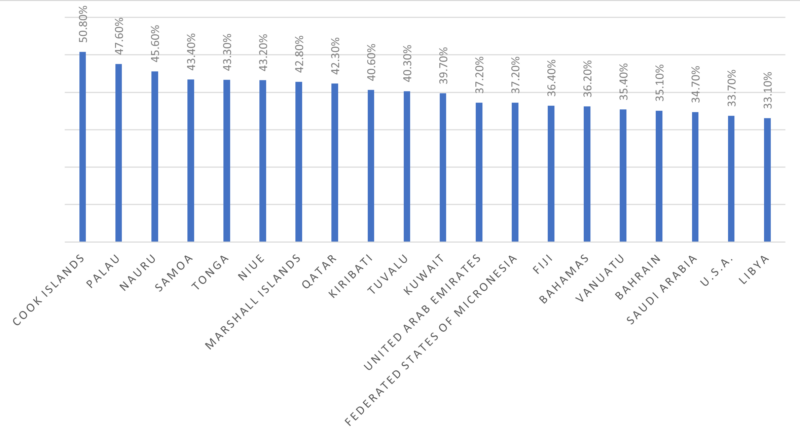

Promoting Healthy Lifestyles (SDG 3.4)

Living a healthy lifestyle is important to both physical and mental health. SDG subgoal 3.4 is targeted at reducing the incidence of chronic diseases given that many are directly linked to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors such as a poor diet, lack of physical activity, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption. According to WHO, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, respiratory diseases, and diabetes – the risk for which increases with unhealthy lifestyle – account for more than 80% of all premature non-communicable diseases and disability worldwide.

Healthy lifestyle behaviors help reduce the risk of obesity, improve cardiovascular health, prevent type 2 diabetes, and reduce the risk of some cancers. Promoting healthy lifestyles can also reduce the burden of chronic diseases on healthcare systems and society as a whole.

Here are some ways that global healthy lifestyle statistics have improved from the perspective of SDG 3.4 since 2000:

- Increase in physical activity: According to the World Health Organization (WHO), global physical inactivity rates declined from 23.3% in 2000 to 27.5% in 2016. However, physical inactivity remains high in many countries, particularly in high-income countries.

- Reduction in tobacco use: The prevalence of tobacco use has decreased globally since 2000, according to the WHO. In 2000, an estimated 24% of adults worldwide smoked tobacco, while in 2019, the estimated global prevalence of tobacco smoking was 17%.

- Improvement in diet quality: The Global Burden of Disease study found that the quality of people’s diets improved between 1990 and 2017, with the proportion of people following an unhealthy diet decreasing from 61.4% to 57.8%.

- Reduction in alcohol consumption: The WHO reported that global alcohol consumption per capita decreased slightly from 2000 to 2016, although it varies widely across countries and regions.

Japan has become a shining star in the promotion of healthy lifestyles in recent years. According to the World Bank, life expectancy in Japan increased from 83.1 years in 2010 to 84.6 years in 2019. A key factor in this evolution is a series of National Health Promotion measures, first introduced by the Japanese government in 1978. Reviewed and updated approximately every 10 years, Japan’s National Health Promotion plan is currently under its fourth revision, knowns as Health Japan 21.11

Japan’s promotion of healthy lifestyles encourages healthy eating, physical activity, and smoking cessation. It also includes education programs, public awareness campaigns, and support for workplace health promotion programs. The dramatic reduction in the smoking rate in Japan, decreasing from 26.3% in 2010 to 17.8% in 2019, is one of the initiative’s most visible successes.

According to a study published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OEDC) in 2017, Japan ranks first among all developed countries with an adult national obesity rate of less than 4 percent. By contrast, CDC’s 2017 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that nearly 42 percent of American adults aged 20 and over can be characterized as obese. WHO data indicates the death rate attributable to heart disease among Americans is more than double (73.92 to 30.62) the rate in Japan.

Denmark is another country that has made similar progress in these areas. The Danish Health Authority has developed a national program called “Healthy Life for All,” which aims to promote healthy eating, physical activity, and mental well-being in local communities. According to the European Health Information Gateway, the smoking rate in Denmark decreased from 22.5% in 2010 to 16.5% in 2020, reflecting efforts to reduce smoking rates through policy and education interventions. The country also ranks in the top 10 among developed countries for lowest obesity rate (<15%). As a result, Denmark’s life expectancy increased from 79.9 years in 2010 to 81.4 years in 2019.

Invest in Our Planet

There is no doubt that as we join together and celebrate Earth Day 2023, environmental sustainability should be at the fore. Still, continuous improvement in our Public Health efforts remains key in that equation. Despite many successes and indicators of progress, inequalities in health and access to healthcare persist between and within countries, resulting in significant disparities in health outcomes and an increasing burden to society as a whole.

Just as collaborative efforts toward environmental health are required to achieve success on a global scale, Public Health challenges are global in nature. The need for investment is not exclusive to either objective. ‘Investing in our Planet’ on this Earth Day and beyond demands coordinated international efforts. International cooperation can facilitate sharing of knowledge, resources, and best practices, which in turn can accelerate progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals to promote a healthy planet and healthy people.

Take some time this Earth Day to learn more about how you can help make the achievement of SDG3 – Good Health & Wellbeing – a reality.

*References can be found here.