Walkerton, a serene town in Bruce County, Ontario, with a population of under 5,000, embodies tranquil rural charm, where close-knit communities thrive amid picturesque landscapes. Here on May 15, 2000, the local public utilities commission took a routine sample of the water supply and discovered E. coli contamination. The commission didn’t notify public health officials.

In the following days, several people fell ill with bloody diarrhea. The local public utilities commission reassured officials a couple of times that the water supply was safe, even though cases kept rising. By the time health officials finally warned the community against consuming untreated tap water, over 40 individuals had already sought medical attention at the hospital.

The Walkerton E. coli outbreak that saw 2,300 people fall ill, and seven die, was the worst public health disaster involving municipal water in Canadian history.

Prior to the outbreak, heavy rainfall in Walkerton led to surface runoff containing E. coli – bacteria found in the environment, foods, and intestines of people and animals. It originated from the manure spread on a nearby farm and entered the drinking water. Insufficient chlorine allowed bacteria and organic matter to overwhelm the system, leading to the contamination of the supply.

E. coli is one of the most common foodborne pathogens capable of triggering outbreaks and, in severe cases, leading to fatalities. Each year, unsafe food leads to 600 million cases of foodborne illnesses worldwide and results in 420,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates from 2015.

The cases of illnesses from foodborne pathogens decreased amid the pandemic, attributed to changes in behavior, public health interventions, and alterations in healthcare-seeking and testing practices. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that in 2022 the risk of getting sick from unsafe food has gone up and returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Impact of Foodborne Pathogens

Foodborne pathogens have become a major threat to public health worldwide. Every year, around one in six Americans (or 48 million people) get sick from foodborne diseases – that’s in the country with one of the safest food supplies in the world. Among them, 128,000 end up in the hospital, and 3,000 die.

Foodborne pathogens, such as viruses, bacteria, and parasites, can make us sick when they get into our food or drinks. Once the pathogen is consumed with food, it starts to multiply inside the human host, and that’s when we get foodborne illness. Alternatively, a toxigenic pathogen can take hold of a food product and produce a toxin that we can ingest.

Scientists have recognized over 250 foodborne diseases and 31 known pathogens. Certain groups, such as older individuals, young children, pregnant women, those with compromised immune systems, or individuals with heightened exposure to harmful germs, are particularly susceptible to these illnesses.

As a result, foodborne illness is typically categorized as either (a) foodborne infection or (b) foodborne intoxication. In cases of foodborne infections, the time between ingestion and the onset of symptoms is usually longer than that of foodborne intoxications, mainly because of the incubation period. Typical signs of foodborne illness include diarrhea and/or vomiting, usually persisting for a duration of one to seven days. Additional symptoms may encompass abdominal cramps, nausea, fever, joint/back aches, and fatigue.

When two or more people get sick from eating the same food, it’s called a foodborne disease outbreak. Many believe that these outbreaks usually happen when people consume the same contaminated food at a restaurant, but they can also occur among individuals who are geographically distant. In such cases, the contamination typically originates at the site where the food was grown or prepared before being distributed to different places.

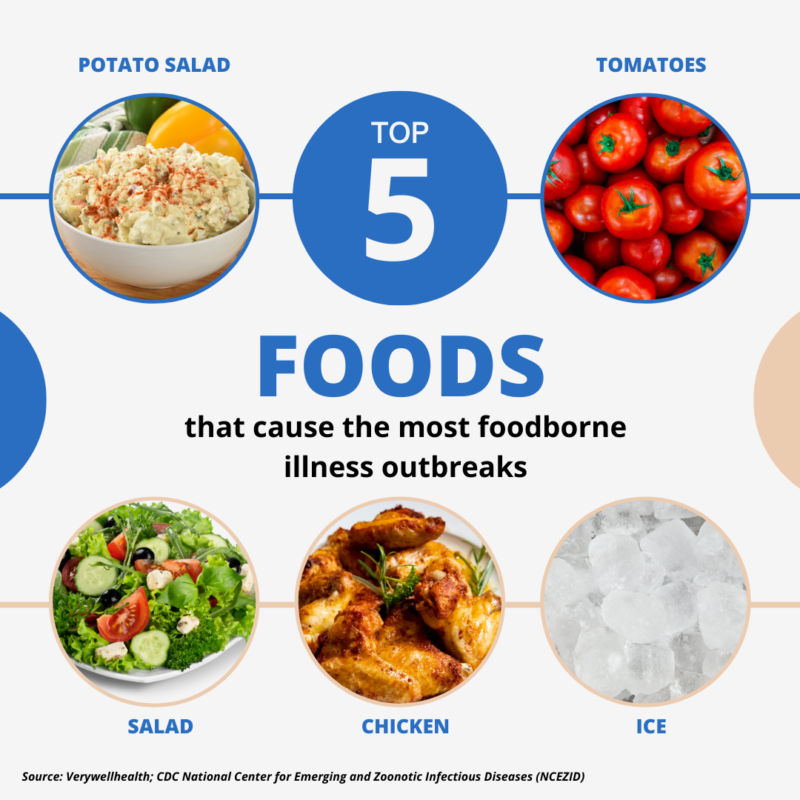

Over the years, foodborne illness outbreaks have been linked to various contaminated foods and beverages, including chicken, beef, pork, fruits, vegetables, raw dairy products, seafood, and processed items like flour, cereal, and peanut butter. Raw or undercooked meat, as well as animal products such as eggs or milk, pose a higher risk of carrying harmful germs that can lead to illness and contribute to foodborne outbreaks.

During slaughter, meat and poultry can get exposed to small amounts of intestinal contents and get contaminated. Cross-contamination happens when germs from raw food get onto surfaces or utensils. Re-contamination occurs if fully cooked food touches raw items or their juices. When it comes to fruits and vegetables, foodborne pathogens can remain on their skin and if not washed properly, can be transferred to the flesh. Processed foods like granola can get contaminated through the use of contaminated raw ingredients, inadequate equipment sanitation, or improper hygiene practices during production.

The top five germs causing illness, hospitalizations, and deaths from food eaten in the United States are Norovirus, Salmonella (non-typhoidal), Clostridium perfringens, and Campylobacter, and Staphylococcus aureus. Toxoplasma gondii and Listeria monocytogenes are the leading causes of death among foodborne pathogens.

Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria are common bacterial culprits found in raw foods, while Norovirus and Hepatitis A are notable viral infections linked to contaminated water and food. Parasites like Toxoplasma and Giardia can cause illness when ingested through undercooked meat or contaminated produce. Fungi, primarily molds and mycotoxins, spoil grains and nuts, producing harmful toxins.

Evolution of foodborne pathogens

The first documented case of a known foodborne illness dates back to 323 B.C., to Alexander the Great. Researchers from the University of Maryland, delving into historical accounts of his symptoms and demise, suggest that he probably fell victim to typhoid fever caused by Salmonella typhi.

Researchers investigating Jamestown’s history in Virginia, assert that the same typhoid fever led to the death of more than 6,000 settlers from 1607 to 1624. It also played a significant role in the fatalities during the Spanish-American War in 1898.

The first known carrier of typhoid fever in the U.S. was Mary Mallon, who had migrated from Ireland. An asymptomatic carrier herself, Mary became a cook and unknowingly spread typhoid fever to numerous households, causing outbreaks and infecting over 3,000 people by 1907.

The turning point came in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the advent of microbiology.

As scientific knowledge advanced, so did the ability to detect and control these pathogens. The mid-20th century saw the development of vaccines and antibiotics, providing new tools to combat foodborne diseases.

But even with immense progress in medicine and technology, outbreaks persisted.

“And it is believed that the next pandemic might be not viral, but bacterial and, specifically, bacterial species that are multidrug-resistant”

Antonello paparella, university of Teramo, Italy

South Africa experienced the largest outbreak of listeriosis globally, marked by a continuous rise in disease cases from January 2017 to July 2018. The National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) reported 1,060 confirmed laboratory cases, resulting in 216 recorded deaths.

According to CDC estimates, listeriosis ranks as the third primary cause of death resulting from foodborne illnesses in the U.S., with a case-fatality rate of approximately 20%. The California listeriosis outbreak in 1985 associated with Mexican-style cheese affected 142 residents of Los Angeles County, resulting in the deaths of 10 newborns and 18 adults, along with 20 miscarriages. The suspected cause of the outbreak was unpasteurized milk used in Jalisco Products’ Mexican soft cheeses. Pasteurization is a heat treatment process that eliminates harmful bacteria, including listeria, from the milk. When milk is not pasteurized, these bacteria can survive and multiply.

In the summer of 2008, a listeriosis outbreak struck multiple Canadian provinces, lasting until December and resulting in 57 confirmed cases and 22 deaths. The cases were traced back to two Maple Leaf Foods’ production lines in Toronto, Ontario, and contaminated products included ready-to-eat sliced cold cuts that had been widely distributed across Canada.

One of the deadliest outbreaks of E. coli happened in Germany in 2011 and took the lives of 53 people. It was primarily linked to contaminated fenugreek sprouts, which were imported from Egypt and caused another outbreak later in Bordeaux, France.

The most recent outbreak of salmonella in the U.S. has been linked to cantaloupes. Over 302 people have fallen ill across 42 states, and four have died.

Despite advancements in treatment and prevention mechanisms, ongoing outbreaks persist due to multiple factors. One of them is the continuous evolution of pathogens. Foodborne pathogens, the microorganisms responsible for causing diseases, have demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt and develop resistance to various interventions.

Foodborne pathogens may encounter various stresses during food processing, preservation, or storage, such as exposure to acids, oxidants, osmotic pressure, heating, and freezing. For example, food preservation and sanitation methods aim to get rid of harmful foodborne pathogens, but sometimes these processes create stress for bacteria without completely killing them. When bacteria face partial stress, they activate alternative sigma factors, leading to the production of proteins that help them cope, like forming biofilms and resisting antimicrobials. This stress adaptation in bacteria can improve their ability to survive and make them more virulent.

In response to stressors, food pathogens tend to mutate. And some can become more dangerous. In a recent study focusing on Salmonella, Brazilian researchers examined how different strains affect the immune response in chickens. They found that a mutant strain of Salmonella enteritidis triggered a higher immune response and therefore, more severe infection, compared to the wild-type strain.

Another intervention that foodborne pathogens have developed resistance to is the use of antibiotics. While crucial for treating bacterial infections, it has led to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains.

Antonello Paparella, Full Professor of Food Microbiology at the University of Teramo in Italy, said, contrary to common belief, in Europe antibiotics are no longer used to promote weight gain or enhance performance in animals. Instead, they are primarily used when an animal is ill and needs treatment. He attributes the responsibility for antibiotic resistance to humans who tend to unnecessarily take antibiotics to treat mild ailments like the flu. After people combat infections, the genes of the defeated pathogens, including antibiotic-resistance genes, can persist and spread. As a result, they create challenges in treatment success.

“And it is believed that the next pandemic might be not viral, but bacterial and, specifically, bacterial species that are multidrug-resistant,” Paparella said. Infections resulting from drug-resistant bacteria claim approximately 700,000 lives in a year globally, with the WHO forecasting a potential increase to 10 million by 2050 if current trends persist.

A recent study found drug-resistant bacteria in 40% of meat samples from Spanish supermarkets. Drs. Azucena Mora Gutiérrez and Vanesa García Menéndez from the University of Santiago de Compostela-Lugo conducted a study testing 100 randomly selected meat products, such as chicken, turkey, beef, and pork, from Oviedo supermarkets. While 73% of the meat samples met safe E. coli levels for consumption, half of them harbored multidrug-resistant and potentially pathogenic strains.

Another piece analyzed 332 studies in 36 countries from 2010 to 2020 and found that antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) bacteria in food have become a concerning global problem. More than 10% of tested food samples showed the presence of AMR foodborne pathogens.

The study in 2022 examined E. coli bloodstream infections in Ontario, Canada, from 2017 to 2020 and found that antibiotic resistance was associated with increased mortality, particularly for commonly used treatment classes.

Also in 2022, an outbreak of salmonella was linked to chocolate produced in Belgium and distributed to at least 113 countries. Up to 450 people, mostly children under 10, got sick but there were no fatalities. The outbreak strain showed resistance to six types of antibiotics, the WHO reported later.

With chocolate, technologically, the risk increases because many chocolate manufacturers don’t start with cocoa beans but instead purchase liquid chocolate. During transportation, the liquid chocolate is kept at a temperature of around 44-45 degrees Celsius, providing an ideal environment for potential contamination. If the cocoa beans were contaminated prior, perhaps in tropical countries during the drying process, or if animals like birds or rats contaminate the beans during storage, this can lead to Salmonella contamination in the final chocolate product, as stated by Antonello Paparella.

Globalization and increased interconnectedness facilitate the rapid spread of infectious agents across borders. Consumers on one side of the world can be impacted by unsafe food produced on the opposite side, challenging health systems to respond effectively.

Climate change and foodborne pathogens

As the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) concluded, “food safety is vulnerable to climate change”. Changes in the environment also highly affect the transmission of foodborne pathogens. Fluctuations in environmental factors, like increases in air and water temperatures, can influence the geographical spread, diversity, abundance, and seasonal patterns of pathogens in both natural and farm environments.

“This increases our risk of exposure to both food and water-borne hazards,” Keya Mukherjee, FAO Food Safety Specialist said in a talk in 2021.

Studies in different parts of the world have concluded that climate change will likely cause a rise in foodborne pathogens. A piece published in the Journal of Health Monitoring found that foodborne diseases are expected to pose higher risks to public health in Germany. The incidence of infections caused by bacteria shows a positive correlation with higher maximum temperatures and increased precipitation levels, researchers found. Higher temperatures favor Salmonella growth in contaminated foods, often linked to inadequate preparation and refrigeration during outdoor activities like barbecues or picnics.

“According to Zhang et al., an increase of 8.8% in the number of weekly cases can be expected for a 1°C increase in the mean weekly maximum temperature. With a 1°C increase in the mean weekly minimum temperature, a 5.8% increase in the weekly number of cases can be expected,” the study said.

Researchers in the U.S. found that warming trends observed in the country, particularly in the southern states, could potentially elevate the incidence of salmonella infections. For example, in Mississippi, a 1°F rise in temperature can result in an increase of four cases of salmonella infections.

The findings from another study in the U.S. indicate that instances of non-cholera vibrio infections in the country could rise by 50% by 2090 compared to 1995 due to elevated sea surface temperatures linked to moderate increases in greenhouse gas concentrations. If global warming is not addressed, the increase could be over 100%. Vibrio bacteria flourish in brackish and marine environments, and in the United States, they are commonly present in coastal regions, with the highest occurrence during the warm summer months. Vibrio vulnificus has a mortality rate of nearly 33%, and it is accountable for over 95% of deaths related to seafood consumption in the country.

Newly Identified Pathogens and Related Outbreaks

As food production and distribution methods change, newly identified pathogens keep emerging.

Despite preventive measures, foodborne illnesses remain a significant public health threat, especially with frequent dining at fast-food restaurants and the use of processed foods. Modern intensive farming also contributes to the emergence of new pathogens, while unsafe agricultural practices and antibiotic resistance further complicate the situation.

Recent research from the CDC revealed that multiple outbreaks of foodborne illness can be attributed to a new strain of E. coli. As reported in the summer of 2023, the study pinpointed a particular bacterial strain linked to leafy greens as the origin of a persistent enteric illness since late 2016.

In Europe, a rare hospital-associated pathogen, Streptococcus zooepidemicus, has surfaced in unexpected places, notably in Italy through cases linked to the consumption of raw milk cheese. Previously confined to hospitals and older individuals with compromised health, a recent outbreak has shown a broader impact, stated Paparella.

The prevalence of outbreaks and emergence of newly identified foodborne pathogens leads to increased financial burden. According to the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS), the expenses related to 15 foodborne illnesses in the United States increased by $2 billion, rising from $15.5 billion in 2013 to $17.6 billion in 2018, driven by inflation and income growth.

In 2015, WHO estimated that unsafe food results in an annual loss of $110 billion in productivity and medical costs for low- and middle-income economies. These efforts play a crucial role in reinforcing political commitments to enhance food safety through better allocation of resources and more effective decision-making in risk management.

Consumer Awareness and Education

The food safety chain involves a collaborative network of producers, manufacturers, distributors, suppliers, retailers, and last but not least – customers. Consumers have the right to assume that the food they buy and eat is safe and of good quality. But, as the last link in the food supply chain, they are also responsible for ensuring that the safety chain remains unbroken.

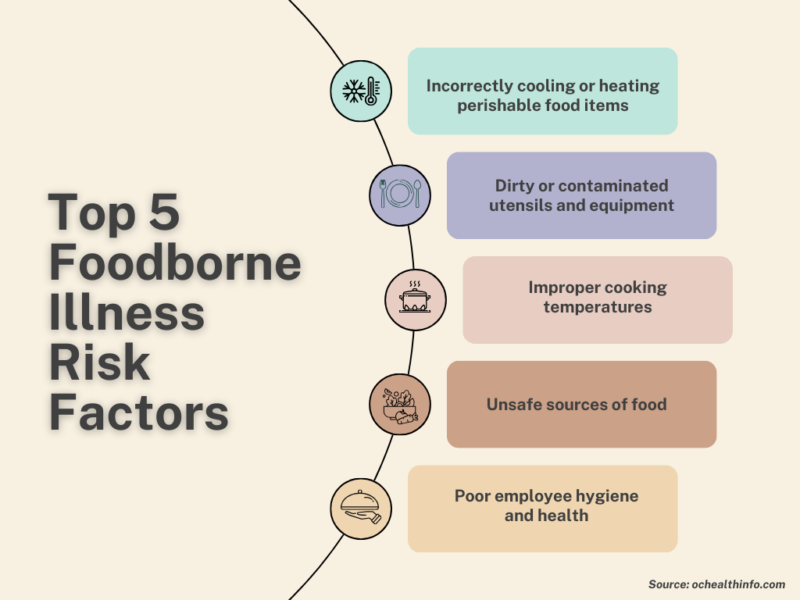

Poor consumer food handling practices, such as inadequate cooking or improper storage, can lead to the consumption of contaminated food. And that, in turn, can result in foodborne illnesses and potential outbreaks.

There is limited understanding of how these behaviors contribute to the contamination of home kitchens with foodborne pathogens, as only a few studies have explored the kitchen’s role as a reservoir for such pathogens.

The findings from an ethnographical study in Italy showed that despite knowing proper food safety behaviors, families often neglect them. Microbiological risks, like inadequate handwashing and improper food handling, were common in families observed.

In another study of 100 homes in Philadelphia, researchers explored microbial contamination in kitchens and its connection to unsafe conditions. Results showed that 44% of homes had fecal coliforms, primarily in kitchen sinks and cleaning tools, and 45% tested positive for at least one foodborne pathogen. Sponges and dishcloths were identified as both reservoirs and vectors for bacteria in the kitchen.

A recent USDA study examined participants’ food safety practices. According to the study, “87% of participants self-reported they washed their hands before starting to cook in the test kitchen. However, only 44% of participants were observed doing so before meal preparation. In the study, 50% of participants used a food thermometer to check the doneness of the sausage patties. However, 50% of those participants did not check all the patties with a food thermometer.”

Meanwhile, the FDA’s Food Safety and Nutrition Survey (FSANS) in 2019, conducted with an address-based sampling method, revealed that customers are more concerned about getting a foodborne illness from restaurant food than home-cooked meals, with 29% thinking it’s “very common” in restaurants compared to 15% at home.

Customer responsibility doesn’t lie only in keeping the food safety chain going. But also in demanding safer food practices and holding the governments accountable. Malachy Mitchell, a Global food and agribusiness and asset management professional said customers are one of the drivers for the adoption of food safety standards, together with producers, retailers, and competitors.

Chris Hegadorn, the Secretary of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS), emphasized the crucial role of consumers in advocating for safe food from producers and retailers.

“We see the role of consumer associations as key actors to represent consumer voices. Civil society is there to pressure governments and organizations to take food safety reform seriously,” he said during a webinar in 2022.

Industry Response

A recent report from the CDC found that sick employees significantly contribute to the spread of foodborne illnesses in restaurants and other food establishments. Over the period from 2017 to 2019, approximately 40% of foodborne illness outbreaks with known causes were linked to contamination by a sick or infectious worker.

The report emphasized the need for comprehensive sick worker policies in restaurants, urging establishments to enforce guidelines that require employees to notify their managers when experiencing symptoms and stay home if unwell. While many restaurants have some sick worker guidelines, the report found that these policies are often incomplete.

Meanwhile, studies indicate that having paid sick leave could enhance food safety results. In a restaurant chain, increased paid sick leave led to a decrease in instances of employees working while unwell, and regulations supporting paid sick leave were linked to a reduction in foodborne illness rates.

Following the 2015 E. coli outbreak, Chipotle took significant steps to enhance its food safety measures, including the implementation of comprehensive testing procedures, changes in food preparation protocols, and increased transparency about sourcing and supply chain practices.

On September 2, 2021, major poultry industry players in the U.S., including Butterball, Perdue Farms, Tyson Foods, and Wayne Farms, joined forces with advocacy groups and experts to address Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack. Together, they raised concerns about outdated food safety standards in the poultry industry, pointing out flaws in the Salmonella performance standard method, the need for modernized Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) plans to extend to the farm level, separate standards for Salmonella and Campylobacter, and the requirement for continued research to ensure sustained progress in reducing these foodborne pathogens.

In 2023, the USDA revealed an investment exceeding $43 million in research, innovation, and expansion for meat and poultry processing. This initiative aims to bolster the ongoing endeavors to revamp the food system across all stages of the supply chain.

Over the years the handling and processing of foods has developed and new products have emerged, leading to a change in where food pathogens are found.

“New products have new problems, and you can find pathogens in places where you could never expect to find them,” Paparella explained.

“Now we know that there is no food that can be considered 100% safe.”