Initially, doctors in the Tuzla Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina thought the rash on young Imran’s* stomach could be scarlet fever. Or maybe it was Kawasaki disease. As reported by Eurosurveillance, that was in early December 2023. By Christmas, four of Imran’s preschool classmates had been admitted to the hospital with measles. By mid-January 2024, another epidemiologically linked case – again originally misdiagnosed as the much less contagious scarlet fever – presented in a neighboring canton. Two more quickly followed. Between the last week of December and the middle of February, the Balkan nation had reported 141 new measles cases.

Barts Health Trust’s Dr. David Harrington said the misdiagnoses should not be unexpected.

“Many front-line clinicians won’t have seen measles for several years,” he told Medscape UK. “So good education and training and collaboration between public health and infection specialists with those in primary and emergency care is key.”

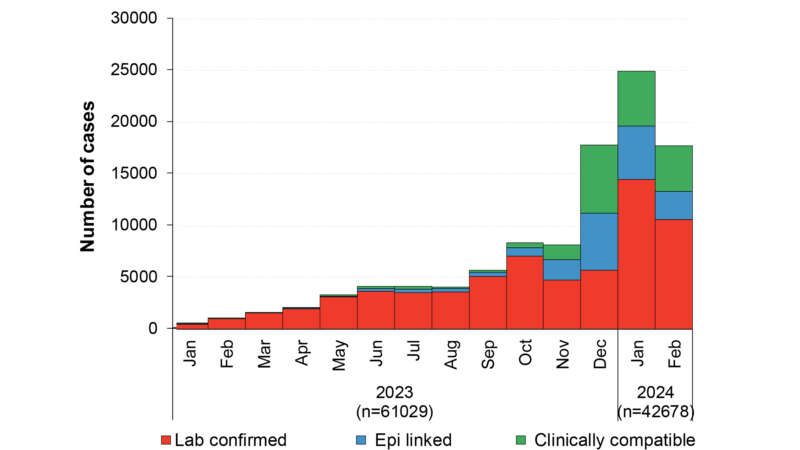

The cases in Bosnia and Herzegovina are hardly unique. Europe reported more than 61,000 measles cases last year, a 60-fold increase over 2022. Half of the 2023 cases came in the last quarter, and that trend has only intensified in 2024. The World Health Organization (WHO) chronicled 42,678 European measles cases in just the first two months of this year. While Eastern Europe, especially the former Soviet republics, has been the hardest hit, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) notes that the measles outbreak has been observed in 40 of the 53 European Region countries. The developed countries of Western Europe have not been spared. Even England, which regained its measles eradication status in 2017, has been deluged by 811 new cases this year, and over 1,000 since the outbreak began, the most in a decade.

Like England, the United States has officially eradicated measles, achieving that status in 2000. But it, too, has experienced a spike. U.S. Healthcare surveillance systems reported 113 measles cases in 2024. By contrast, the nation experienced only 241 cases over the previous four years combined. As of April 30, 18 U.S. states, from California to New York, Washington to Florida, have reported cases, including seven outbreaks of more than three instances. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that 82 percent of those patients were either unvaccinated or their vaccination status was unknown. Only five percent of the people contracting measles were known to have received the recommended two-dose inoculation. Half the U.S. patients have been age 5 and under; the other half has been divided equally among children and adolescents 6 to 19 and adults 20 and over. Two-thirds of the young children and 60 percent of the adults contracting the disease required hospitalization.

“Risk for widespread U.S. measles transmission remains low because of high population immunity,” CDC stated. However, “this year, the U.S. is at greater risk for measles outbreaks because decreased vaccination worldwide has led to more cases internationally. People who are not vaccinated may encounter measles when traveling abroad and return to the U.S. with measles. Additionally, declining U.S. vaccination rates increases susceptibility to outbreaks.”

The CDC report notes that nearly all (96 percent) of the U.S. cases involved patients who either recently travelled abroad or came into contact with someone who recently returned from overseas.

While CDC emphasized that “overall measles outbreak risk to the general population is low,” the recent spate of cases has put the U.S.’s measles elimination status in jeopardy. To maintain the designation, a region must experience no outbreaks of 12 months or more. America’s designation has not been at serious risk since 2019 when under-vaccinated communities in New York City and upstate New York were affected.

Measles Never Went Away

in which Rāzī examines a young measles patient. Wellcome Images

One of the world’s most contagious diseases in the world, the measles virus plaguing Europe and much of the rest of the globe today mutated from bovine rinderpest some 2,500 years ago. It adapted quickly to human hosts, even as its cattle- and buffalo-borne precursor was declared officially eradicated in 2011.

Abū Bakr Muhammad Zakariyyā Rāzī, a 10th-century Persian physician was the first to identify measles as a condition distinct from smallpox. As travel and exploration became more prevalent during the Renaissance, so too did measles’ reach. Isolated civilizations, especially the indigenous peoples of the South Pacific were decimated by measles brought to their islands by explorers and traders in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1757, Scottish doctor Francis Home determined measles to be a pathogen, present in patients’ blood, and easily transmittable to others via personal contact. From the 1920s through the 1960s, “major epidemics occurred approximately every two to three years and caused an estimated 2.6 million deaths each year.

Research by doctors John Enders and Thomas Peebles and their team at Harvard led to their perfection of a live attenuated measles vaccine in 1958. Quickly licensed in the United States and mass produced for use around the world by 1963, the vaccine has been saving countless lives ever since.

Children ideally receive two doses, often in combination with vaccines for mumps, rubella (MMR) and varicella (MMRV). The first is administered to children around nine months of age in highly susceptible countries – 12 to 15 months in other countries. The second dose should be given three to six months later. At a cost of about $1 per child, the measles vaccine has prevented 56 million deaths in the 2000s, according to WHO.

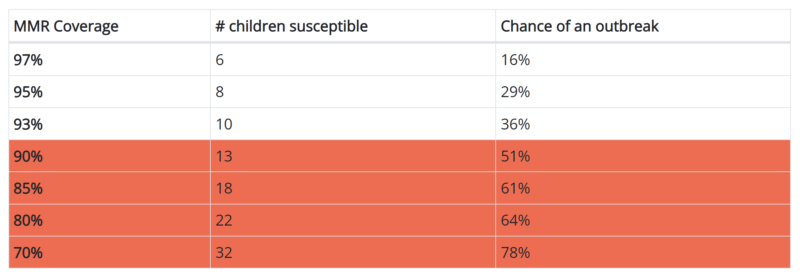

Still, given the virus’s highly contagious nature and the need for vaccination of at least 95 percent of a given population to protect it via community (herd) immunity, measles remains a major public health concern, especially in the Global South. More than one quarter of the world’s children – some 22 million – do not receive both doses.

Transmitted when a person breathes air containing an infected person’s nose and throat secretions expelled through sneezing, coughing, or mere exhalation, measles primarily affects children under age six. In the developed world, most cases are benign, resulting in a blotchy rash, runny nose, and fever that subside in a week or less.

More severe cases, however, are far from rare and can include dangerously high fever, diarrhea, ear infection, pneumonia, and even encephalitis.

The most profound complications are found in babies under six months of age, adults over 20, pregnant women, and people with other health concerns, compromised immune systems, and comorbidities. ECDC estimates 140,000 children die each year from the disease, many from subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE).

While there is no universally effective treatment for patients who contract measles, healthcare providers recommend tactics for relieving symptoms and discomfort and measures designed to mitigate the chance of complications. These include forcing fluids to replace those lost from vomiting and diarrhea and eating a healthy, well-balanced diet to maintain strength and immune system resilience. Because “multiple studies in populations in which vitamin A deficiency is prevalent have shown that…improving vitamin A status can dramatically reduce the risk of serious complications and death from measles, with minimal detectable incidence of adverse effects,” WHO now recommends two daily doses of vitamin A be administered to all patients, even in areas where deficiency is not a common problem.

Reasons for the Resurgence

Measles’ re-establishing a foothold in the developed world after years of latency can be traced to a single factor – lower global vaccination rates. For a region to maintain herd immunity, 95 percent of its population must be vaccinated. Pre-Covid, most countries had not reached that level, with about 86 percent of the world’s children receiving both recommended measles inoculations by age 2. The pandemic reduced those rates precipitously, to 81 percent in 2021. The causes, however, are nuanced and interrelated:

Covid-19 – Measles cases dropped dramatically during the Covid crisis, the combined result of remote schooling, mask use, self-quarantines, and the halting of international travel. But with the lifting of social and business restrictions, the measles exposures rose to alarming levels. The lockdowns resulted in missed doctor’s appointments and skipped measles vaccines. WHO estimates that 22 million children around the world who should have received their first injections during the pandemic did not receive them. Another 11 million missed their second dose, WHO says.

Ignorance and Underestimation – In the U.S. and much of Europe, measles has been out of sight, out of mind for most parents. Thanks to herd immunity, few families even consider the possibility of their children’s being exposed. Medical Science Monitor editor Dinah Parums, Ph.D., suggests that this “complacency” conceivably plagues “populations and healthcare professionals who may not remember how severe measles infection and its long-term sequelae can be.”

And because nearly all measles cases in the U.S. and Europe are free of complications, parents may not fully appreciate its severity. Symptoms typically linger for a few days to a week, so parents falsely equate measles to a cold or strep throat. But “Measles is not just some minor virus that all kids get in childhood,” reminds Dr. Sarah Lim of the Minnesota Department of Health. “It’s not just some little fever or some little rash; it is much more severe, and it is much more dangerous.”

Perhaps healthcare’s quality and availability in the West plays a role, as well, notes Dr. Paul Law, the only pediatrician in Sankuru Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, who has “watched many children die of measles,” he writes. [L]ittle lungs, filled with fluid and racked with inflammation, struggle for oxygen. The victims breathe faster and faster, gasping for air until, exhausted, they stop.

In Dr. Law’s central Africa, where only about 20 percent of the children are vaccinated against measles, “I’ve never met a mom there who turned down the shots for her kids.”

Misinformation and Hesitancy – Vaccination rates are not just falling in areas of the globe where clinics are hard to reach and information difficult to disseminate. Despite the measles vaccine’s proven effectiveness, low-cost, and widespread availability, only 93.1 percent of the U.S. children entering kindergarten have been vaccinated, after the ratio had remained above herd-immunity levels for the past decade. In some states, that rate is as low as 80 percent. According to CDC experts, a 93 percent vaccination rates means that if one child contracts measles and attends daycare with 100 classmates, 10 people would be expected to get sick. Lower vaccination rates would see even greater outbreaks.

“Measles cases anywhere pose a risk to all countries and communities where people are under-vaccinated,” warns John Vertefeuille, director of the CDC’s Global Immunization Division in a conversation with WebMD. “Urgent, targeted efforts are critical to prevent measles disease and deaths.”

Measles vaccine hesitancy is linked to misinformation and mistrust over its effectiveness and possible side effects, trends exacerbated by social media and piggybacking on conspiracy theories surrounding the Covid vaccine. Andrew Wakefield’s study linking a measles vaccine to autism has been thoroughly disproven, his article removed from its publishing journal, and his behavior described by reputable medical scientists as “dishonorable and irresponsible.”

Still, the myth persists, jeopardizing public health, says Rupali Limaye, associate chair for research in the international health department at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“The vilification of this vaccine is still present,” she said.

She cited a 2022 poll conducted by the Kaiser Family foundation in which more than quarter of the parents surveyed agreed that they should be allowed to decide not to vaccinate their children “even if that may create health risks for other children and adults.”

Those attitudes could prove difficult to overcome in the current battle against the disease, says Dr. Catharine Paules, who specializes in infectious diseases at a Penn State Health facility in Hershey, PA. “This really may be the only infection that’s this contagious, so you really have to vaccinate to prevent transmission,” she explained. “It’s really different than other infections that are less transmissible,” Paules said. “We were able to prevent the spread of COVID by doing things like social distancing and masking. But measles is so contagious that you really have to rely on vaccines to get outbreaks under control.”

The Cost: Human, Financial, Social

Unlike less-developed areas of the world, the current measles increase likely will not prove fatal. The last measles-related death in the United States occurred in 2015. Only nine people have died in Europe from measles since 2019, all in the East: Ukraine, Romania, Kosovo, and Albania. Compare this to the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the United Nations reports malnutrition, scarce medical facilities, conflict, and other factors resulted in more than 6,000 deaths from measles in 2023.

That does not mean measled-present areas can escape its devastating effects. Patients often endure fever-induced aches along with throat inflammation and pain from the dry, hacking cough that comes with the disease. Patients also can develop Koplik’s spots and ulcers inside the mouth, making it painful to swallow, conjunctivitis that make the eyes burn, and skin irritations from scratching measles’ distinctive itchy rash.

Measles’ impact extends beyond the medical aspect. Jurisdictions facing a measles emergency incur unforeseen and preventable financial hardships, as well. The last major outbreak in the U.S., five years ago in Clark County, WA with 71 confirmed cases cost an estimated $3.4 million, or more than $47,000 per instance. These outlays extend beyond medical and public-sector response. They also include lost productivity as parents missed work to care for their infected children. As that study’s authors report:

“During a measles outbreak, substantial costs can be incurred by public health departments and the individuals in the community. The resources needed to identify cases and prevent measles among contacts can strain public health resources at the local, state, and national levels. In addition to the costs of responding to and controlling an outbreak, direct medical costs and productivity losses are incurred by individuals who have contracted measles or who were subject to quarantine.”

The current measles crises can exert other pressures:

- Societal – As we witnessed during the Covid era, measles or any threat to public health can strain the social fabric to its breaking point. These pressures infiltrate everyone’s daily life, deepening political rifts and social intolerance and challenging the trust and cohesion that bind communities together. One of the most harmful consequences of the measles increase could result in the erosion of public trust in institutions and health authorities. If a community believes an outbreak has been mishandled, whether through delayed responses, lack of transparency, or ineffective communication, the fallout can include increased reluctance to follow future guidelines or engage with public health programs. Again, as seen during Covid, schools may be forced to close temporarily to control the spread of the disease, disrupting children’s education and placing additional childcare burdens on families.

- Political – Vaccination, a topic already fraught with differing opinions, becomes even more polarized in the context of an outbreak. Debates over vaccine requirements and policies can escalate into conflicts, straining relationships within families, among friends, and between neighbors. Social media platforms, where misinformation can spread rapidly, often exacerbate these tensions, contributing to an environment of mistrust and hostility. Because measles is much more prevalent in the poorest parts of Asia and Africa, immigrants from these regions may be unjustly blamed if the disease appears in their neighborhoods.

- Cultural – Measles outbreaks can force communities to forgo fraternal, spiritual, and social gatherings that bring neighborhoods together. Weddings, funerals, religious ceremonies, school graduations, and family reunions – moments that mark the milestones of human life – could be scaled back, deferred, or radically altered to mitigate the risk of spreading the infection. These adjustments, while necessary, can leave lasting emotional and psychological scars, altering how communities celebrate, mourn, and worship. As people spend more time at home, they may rely on unsubstantiated information on best practices for dealing with measles.

Healthcare Agencies’ Response

Vaccination is the only effective measure to protect individuals from measles. And mass vaccination is the only way to protect communities from measles outbreaks. So, it is understandable that as the number of cases skyrocket agencies throughout Europe and the United States are focusing their efforts on getting more shots in more arms. Most healthcare providers do not have patience for vaccine hesitancy.

“During the pandemic there were obviously a number of people who didn’t like that they were being mandated to receive COVID vaccines, and now that mindset has spilled over into the [measles] vaccine,” Director of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Vaccine Education Center Dr. Paul Offit told Scientific American. “But people can forget that measles is exponentially more contagious than COVID…, and it’s a nightmare.”

Healthcare organizations prescribe specific action healthcare providers should follow to bring the measles crisis under control. These include inoculation “catch-up” campaigns so that “No one [misses] out on the right to the protection that vaccines offer, simply because they are not able to access services in time or for any other reason,” WHO notes. “The importance of scaling up implementation of the national catch-up vaccination is more pronounced when there is an extended interruption of routine immunization services (e.g., due to vaccine shortages or system disruptions caused by outbreaks or epidemics, natural disaster, acute conflict, [or] population displacements….)”

WHO also emphasizes robust surveillance programs “to identify areas of measles or rubella virus transmission which may reveal potential immunity gaps in the population. This will guide effective public health responses to…sustain elimination in post-elimination settings. Effective surveillance programs will identify and confirm measles cases and track their health, financial, and cultural burdens while tracking down outbreak sources and directing mitigation tactics.

Experts advise hospitals, clinics, and providers to check the immunization status of all patients. ECDC says it is particularly important to profile people who are most susceptible to the measles virus and to offer vaccinations for those who need them. Government should do their part by screening migrants and tourists who enter the U.S. or E.U. from countries experiencing low vaccination rates.

Hospitals and provider groups should ensure they have implemented the procedures and infrastructure to adequately investigate cases, track contracts, and quickly isolate and treat patients they suspect may have contracted measles. In Europe, especially, this means efficiently sharing information across national borders.

Because most Western countries have achieved measles elimination status, ECDC says it has become necessary to raise healthcare professionals’ awareness and re-acquaint them with the virus’s symptoms to give them an understanding of “the clinical presentation of measles (e.g. age shift to young adults), to ensure that all cases are diagnosed.” From 2020 to the end of March 2024, the CDC confirmed 338 measles cases; of these, 326 (more than 96%) were deemed to have been imported, mostly from Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. However, the first quarter of 2024 saw increased European and Southeast Asian cases.

Conclusion

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases in the world. Given the decline in vaccination rates in Europe and the U.S., its potential for devastation is higher than at any time in the last decade or more. A single infected person can transmit the virus to dozens of people in crowded areas. For instance, the Los Angeles County health department reports that a person with measles recently visited Universal Studios and other attractions, landmarks, and restaurants while spending several nights in a hotel.

Meanwhile, in England, Forbes reports that the vaccination rate in the Birmingham region – one of the hot spots for measles outbreaks – was around 83% in December 2022 and may have even declined since then.”

The required course of action is clear, according to Medical Science Monitor:

“Public health and primary care initiatives are urgently required in all countries to raise awareness of the dangers of measles infection and the importance of adherence to vaccination programs.”

![]() By Scott Smith

By Scott Smith