Around the world, dengue is considered the most common viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes that affects people. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries. In the first three months of 2024, over five million dengue cases and over 2000 dengue-related deaths were reported globally. The figures so far project that 2024 could be even worse than 2023, with the regions most seriously affected being the Americas, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific.

In the Americas, there were 6,186,805 suspected cases of dengue reported in the first 15 weeks of 2024. To put this into perspective, according to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), this figure represents an increase of 254% compared to the same period in 2023. Of these cases 5,928 were confirmed and classified as severe dengue.

These recent reports from the WHO indicate that many countries across the worst affected regions are struggling to contain dengue outbreaks. It is especially worrying in the regions that are just entering the monsoon season. In April, the World Meteorological Organization stated that forecast models indicate above-average rainfall will hit most of South Asia for the 2024 monsoon season (which usually runs between June and September). If this projection transpires, there will also be increased levels of humidity and flooding which usually correlates with an escalation in dengue cases.

… about half of the world’s population is at risk of dengue.

Dr Raman Velayudha, World health organization

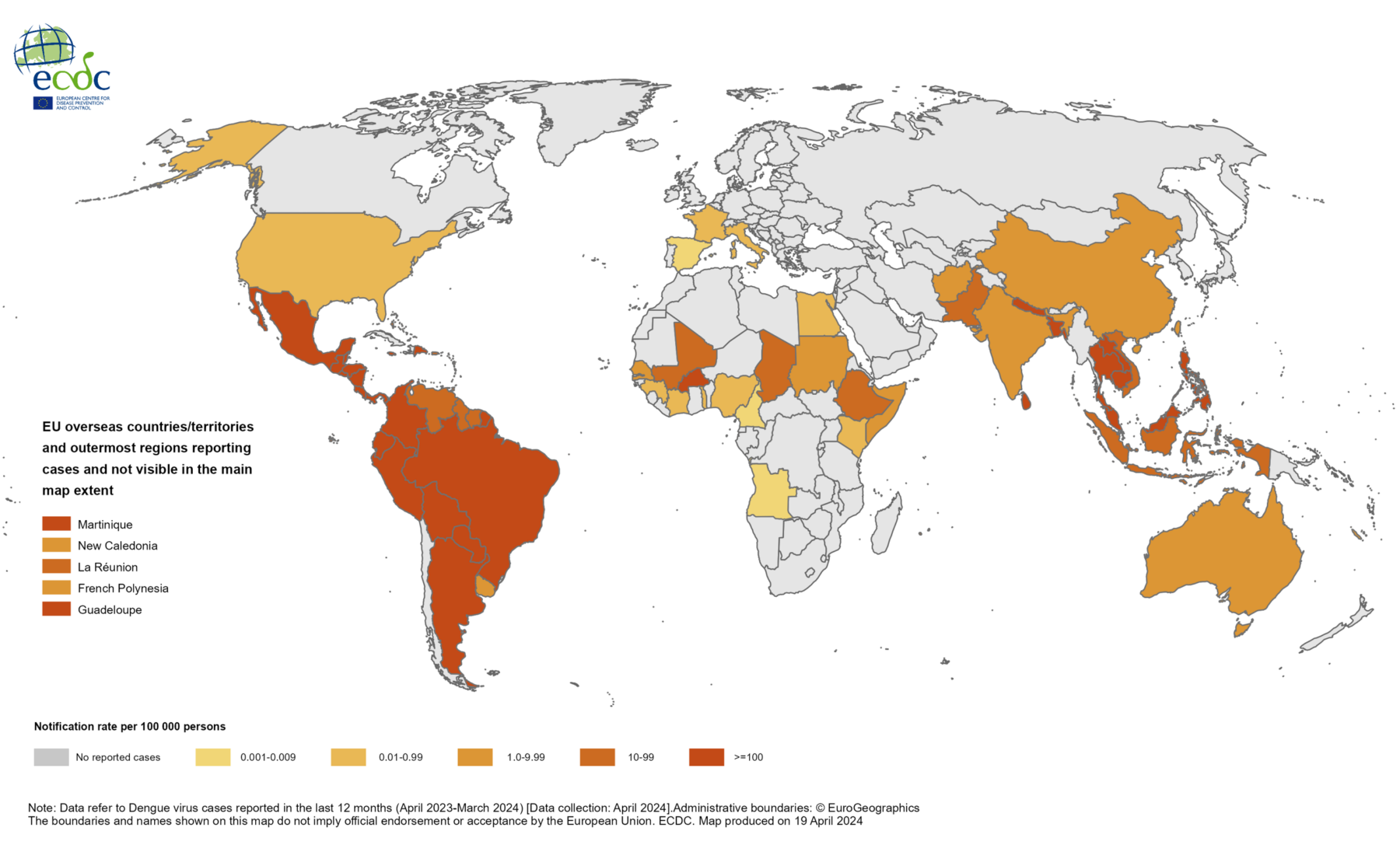

Another concerning trend is that the disease may be spreading in countries outside the tropical and subtropical zones that were previously not considered under threat. As of mid-November 2023, 122 cases of locally transmitted dengue were reported in Europe, in countries including Italy, Spain and France. In France and Spain these cases were distributed around the Mediterranean coast and in urban environments. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported that 71 locally transmitted cases were reported in 2022, a 20% increase from 2021. Usually, cases reported in Europe are imported from endemic regions rather than locally transmitted. The mosquito that spreads dengue is now found in 22 European countries.

Most dengue cases reported in the 49 continental U.S. states occur in travelers infected in areas with risk of dengue. However, there are sporadic cases of locally transmitted dengue in states such as Florida (178 cases in 2023), Texas (1 case in 2023) and California (1 case in 2023), and in 2022 two case were reported in Arizona. The dengue vector is commonly found throughout many areas of the US so local spread of dengue is possible.

The current expansion of dengue could have catastrophic, global implications if a worldwide approach isn’t taken to control the disease.

Dr Raman Velayudhan, WHO’s Head of the Global Program on control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, states that “about half of the world’s population is at risk of dengue.”

What is Dengue and How is it Spread?

Dengue is a viral infection that humans contract from a mosquito bite. The disease is predominantly found in tropical and subtropical climates with a higher concentration in urban areas.

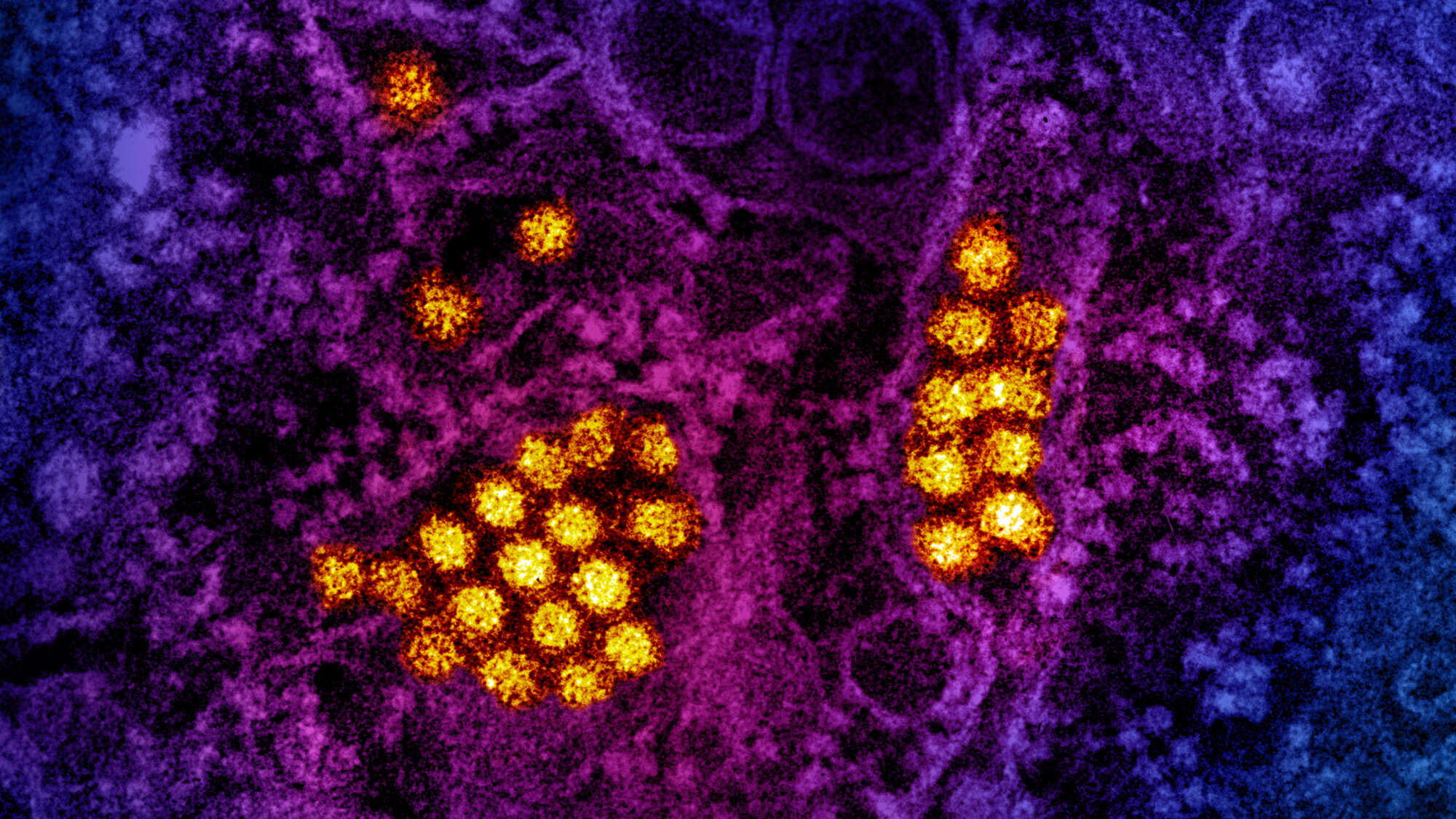

© NIAID 2023

The disease is spread by bites from female mosquitoes, primarily the Aedes aegypti mosquito which is the most widespread mosquito species globally. This type of mosquito also spreads other diseases such as zika, yellow fever and chikungunya. Other mosquito species within the Aedes genus can also transmit dengue, for example, in 2023, a surge in cases in Europe was caused by the Aedes albopictus (tiger mosquito).

Once a person is infected they can increase the transmission rate through infecting other mosquitoes that bite them while the virus is present in their system. Human-to-mosquito transmission is possible up to two days before symptoms appear. Many people who contract the disease only suffer a mild illness or show no symptoms at all, however, the virus can cause more severe cases and even death. When people are infected for the second time they are at greater risk of severe dengue.

Symptoms of the disease usually emerge 4-10 days after the infection and can last from 2-7 days. The normal symptoms include a high fever (40°C/104°F), nausea, vomiting, swollen glands, a rash, severe headache, and pain behind the eyes, in muscles and joints.

Severe dengue usually becomes apparent once the initial fever has passed. These symptoms include: severe abdominal pain, rapid breathing, continued vomiting, bleeding nose or gums, fatigue, restlessness, blood in stool or vomit, pale and cold skin, and excessive thirst. Severe forms are characterized by blood vessels becoming damaged with the presence of hemorrhages, hypotension, thrombocytopenia, plasma leakage, and the number of platelets in the bloodstream dropping. This can eventually lead to shock, internal bleeding, multi-systemic failure and death.

There is no specific treatment to combat dengue. Early detection and medical care increase the chances of survival and recovery.

Analysis of the Geographical Spread

Historically, it is believed that the Aedes aegypti was transported into the Americas and the Mediterranean on ships sailing from Africa and has been present across the tropical regions of the Americas, Africa and Asia for centuries. The early history of dengue has been pieced together from searching historical literature for dengue-like illness and wasn’t accurately documented until the dengue virus (DENV) was first isolated in 1943 in Japan and DENV-specific diagnostics became available in the 1950s.

© NSW Department of Health

It is suspected that around this period, the Second World War facilitated the spread of the disease through the rapid increase in global trade, travel, and urbanization.

Since the 1950s four distinct serotypes of the dengue virus (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4) have been identified. Monitoring the specific serotypes of the virus offers important insight into the disease’s patterns and the way it spreads which can inform projections and future planning. Understanding the geographical distribution of dengue and how it has evolved is essential for determining its contribution to global mortality and effect on specific regions. With limited resources available for tackling global issues such as dengue, mapping, data collection and analysis is required to allocate these resources for an optimum effect on an international scale.

Continental U.S. and Europe were historically both endemic. In the U.S., dengue outbreaks have been reported in the gulf and southeastern states since the first half of the 20th Century, especially in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, and Texas. Europe had a number of documented outbreaks during the 19th and 20th Century in Cyprus, Spain, Greece, Italy, Bulgaria, Turkey, Austria and Malta.

The first evidence of a dengue outbreak in the Eastern Mediterranean Region was in 1799 in Egypt. In the last 40 years the frequency and geographical spread of dengue has since increased, with outbreaks documented in Afghanistan, Djibouti, Egypt, Oman, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen. Other countries such as China and Australia might also be at risk of further dengue expansion.

Assessing the Quality of the Data

While assessing and monitoring global outbreaks of the disease it is important to consider the strength of the data and the sources. Each country has its own system of data collection and criteria of diagnosis. In many endemic countries where the access to health care is limited, many cases go unreported so the true burden of the disease isn’t fully understood. Even the countries and regions where the disease is not endemic, and that do not have the same level of strain on their health care systems, are unable to report the true number of dengue cases from their collected data.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that there are various limitations with their collected data and dengue reporting:

- Mild cases go unreported

- Surveillance systems rely upon healthcare providers diagnosing, lab testing, and reporting confirmed findings to the public health authorities

- Surveillance data is often collected by country of residence or where the patient got tested, this may not be where the disease was contracted

- There is often a lag in case reporting

Between 2020 and 2022, global data shows that there was a reduction in dengue cases most likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic and a lower rate of reporting.

In addition to the CDC reported issues, the more vulnerable regions have additional limiting factors: the disease often displays flu-like symptoms and similarities to other known diseases in tropical regions, such as malaria. The surveillance systems in place are often inadequate and accurate data isn’t collected. There also are limitations on the capabilities of the facilities, healthcare workers, and laboratories to detect and accurately report the disease. Some systems are primarily focused on reporting hospitalized or severe dengue cases. There are also variations in the case definition used across countries.

According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the laboratory criteria for detecting a ‘probable case’, requires the detection of the dengue-specific Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies in a single serum sample. For a laboratory to confirm a case at least one of the following is required:

- Isolation of a dengue virus from a clinical specimen

- Detection of dengue viral antigen, the viral nucleic acid or the dengue-specific IgM antibodies in a single serum sample and confirmation by neutralization

- Seroconversion or a four-fold antibody titer increase of dengue-specific antibodies in paired serum samples

2023: One of the Deadliest Years on Record

Since the beginning of 2023, the unexpected spike in dengue cases has resulted in a historic high. The simultaneous occurrence of multiple outbreaks, the scale of the surge in cases and deaths, and the spreading to previously unaffected regions made it one of the worst years to date, leading to the WHO announcing dengue to be the world’s fastest-spreading tropical disease and a global threat.

The main contributing factors for the increase in dengue cases over 2023 have been attributed to:

- Changing distribution of the vectors (Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes) especially in countries naive to dengue

- El Niño phenomena

- Climate change causing an increase in temperatures, rainfall, humidity and flooding.

- Fragile health systems in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Political and financial instabilities in countries facing complex humanitarian crises and high population movements

ECDC, April 2024

Four of the worst hit countries in 2023 were Bangladesh, Peru, and Burkina Faso – which had the highest known death tolls, and Brazil – which had the highest number of known cases.

Bangladesh

Dengue, previously known as Dacca fever, was first recorded in Bangladesh (then known as East Pakistan) in the 1960s. Between 1964 and 1999, cases were only sporadically reported until the first major outbreak in 2000. Dengue has since become an endemic disease.

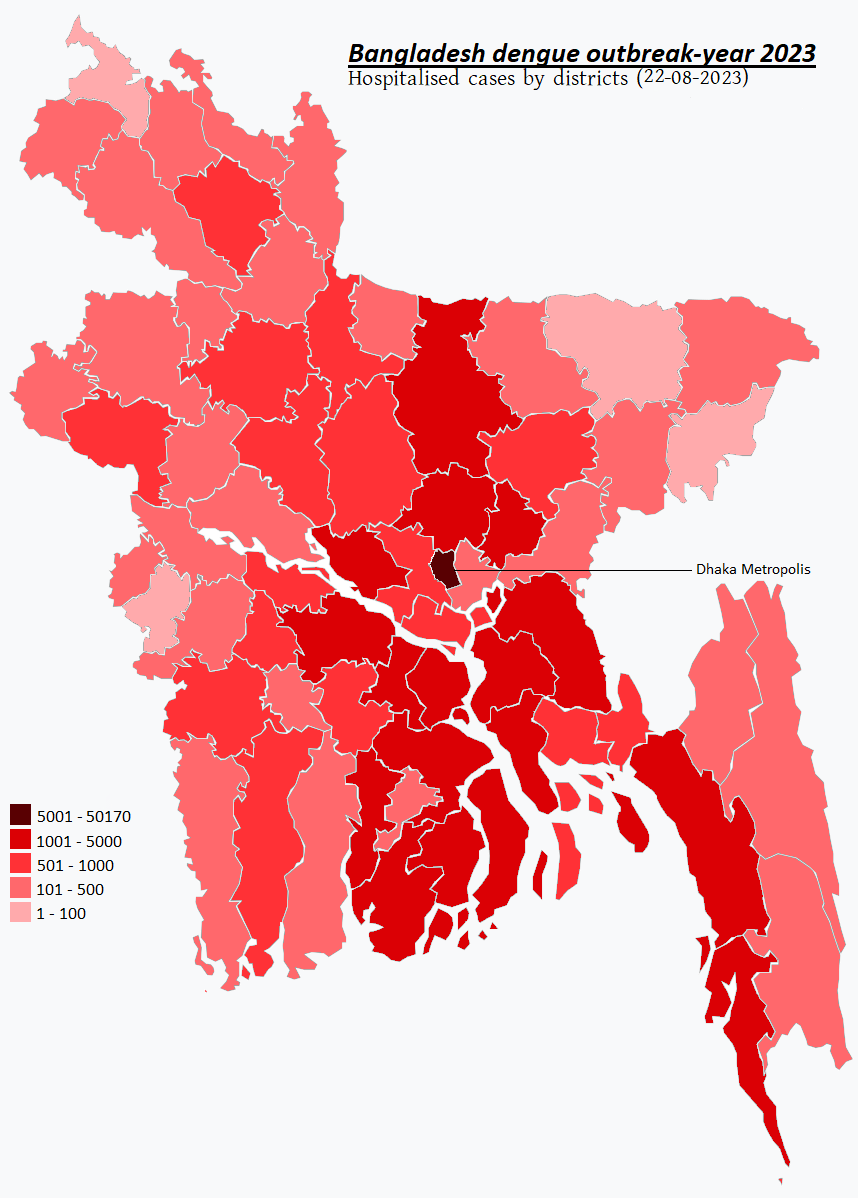

© Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), August 2023

Although outbreaks have been reported in the country since 2000, the 2023 outbreak was by far the worst on record. Over the year, the death toll was around 1598 people with over 300,000 infected (there were 62,000 cases reported in the previous year). The number of cases reported were only made up from data received from government-approved hospitals, the true figure is estimated to be around four times higher. The highest frequency of cases was found among people aged 19-29 years (28.7%) and the highest case fatality rate was found among children aged 0–10 years (12%).

Between 2000 and 2018, Bangladesh’s capital city of Dhaka was typically the epicenter of dengue outbreaks, accounting for 90% of known cases and fatalities. However, what has made the 2023 ongoing outbreak unusual is that over 60% of the cases have been outside of the capital – and the speed at which the outbreak spread across the 64 districts.

Bangladesh’s hot and humid climate creates a favorable environment for mosquito species, including the two most common vectors of dengue. The country’s dengue season usually coincides with the monsoon season (July–August), the time of year with the highest amount of rainfall. During 2019 and 2022 two large outbreaks of dengue occurred during unusual climate patterns. In the case of 2019 there was early rainfall in February, the 2022 outbreak correlates with the late onset of rainfall in October.

These changes in rainfall extended the dengue periods during these years. The same pattern has been recognized in the 2023 outbreak which started in April and surged nationwide during the height of the monsoon. During the year, an unusual episode of increased rainfall along with increased humidity and temperatures, created a thriving mosquito population across the country.

©Sustainable sanitation

In addition to the climate factors, a report in 2021 suggested that the 2019 outbreak was in part due to the introduction of a new serotype (DENV-3). Evidence also suggested that there was a failure of vector-control initiatives due to insecticide resistance. Reports circulated in the media in 2023 about behavioral changes among the Aedes mosquitoes that are rendering mosquito control measures ineffective and a study that carried out tests on Aedes aegypti in the country found that they now have the ability to breed and survive in polluted and diluted sea water.

Two more factors that are believed to have contributed to the 2023 outbreak were mass migration and rapid unplanned urbanization, especially in Dhaka City.

Summary of region-specific factors:

- Unusual climatic conditions increased the period of rainfall

- Mass migration and informal urbanization

- Behavioral changes among Aedes mosquitoes rendering mosquito control measures ineffective

- Development of insecticide resistance

Brazil

Brazil has a long history of dengue with reports of the disease being documented throughout the 19th Century in the largest cities in the country – particularly in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In 2023, Brazil recorded the highest number of cases across the Americas with 2,909,404 cases and 1474 severe cases (neighboring Colombia reported the highest number of severe cases in 2023 at 1504).

Globally, Brazil is the country with the most cases of dengue so far in 2024. In the Americas it is consistently one of the worst affected countries by mosquito-borne diseases. Brazil is predominantly a tropical country with 85% of its population living in cities. There are two metropolises São Paulo (11.45 million inhabitants, situated 760m above sea level) and Rio de Janeiro (6.21 million, 2.13m ASL), and a number of smaller cities including Brasília (2.82 million, 1172m ASL), Fortaleza (2.43 million, 21m ASL) and Salvador (2.42 million, 8m ASL). All of these cities are sitting at an altitude that offers a suitable habitat for the Aedes aegypti mosquito which can thrive in elevations up to 1300m, and are moderately abundant from 1300m to 1700m.

© David Berkowitz

Many of Brazil’s cities also have large areas of inadequate urban planning. These densely populated areas create the perfect breeding ground for the vector and the spread of the disease.

In 2023, it is believed that the El Niño phenomenon was one of the main contributing factors to the outbreak by creating optimum conditions for the mosquito: an unprecedented heatwave, prolonged heavy rains and flooding. Also, all four serotypes of the dengue virus have been detected in circulation in the country which is believed to have diminished the immunologic defenses in people.

Summary of region-specific factors:

- El Niño phenomenon created unusual climatic conditions increased the period of rainfall

- All four DENV types in circulation diminished the immunologic defenses in people

- Highly populated areas of informal urbanization

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso is believed to have suffered its first dengue epidemic in 1925, however little is known about the history of dengue prevalence in the country. The disease has been considered endemic in Burkina Faso since 2013.

Dengue outbreaks were reported in 15 African countries during 2023. Burkina Faso was the most affected country reporting 146,878 suspected cases, including 68,346 probable cases and 688 deaths among suspected cases, accounting for 85% of reported cases and 91% of recorded fatalities in the region.

A variety of factors have been attributed to the current outbreak in the country.

According to UNICEF, the ongoing conflict and humanitarian crisis in the country has had a devastating impact on the population. Over 2023 there was a notable escalation in the frequency and intensity of armed conflict activities between government forces and armed group factions. By the end of July 2023, it was reported that 375 health facilities closed resulting in nearly 4 million people being without healthcare. The conflict has also resulted in waves of civilian displacements, poor living conditions, and mass movement.

©Moorelangue

According to the WHO, there has been inadequate levels of testing and documentation of cases in the country which makes analysis of the ongoing outbreak and management of resources and control methods trickier to implement effectively. The country has also suffered from the dissemination of false rumors about the disease.

In November 2023, the country’s secretary general of the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene, issued a warning discouraging the population against the use of traditional medicine to treat or prevent dengue fever. Despite this, many people are still reported to be using medicinal plants and traditional herbal remedies in an attempt to combat the disease. A proliferation of advertisements on social media has exasperated the situation and violated laws and guidelines in the country.

The use of traditional herbal medicines can carry risks of adverse effects, hepatotoxicity or renal toxicity (due to the possible presence of contaminants such as mercury, lead, and arsenic). However, traditional medicine is often the most economical and available health care for a large number of the African population in rural areas. It is estimated that around 80% of people in developing countries rely upon traditional herbal medicines to treat diseases such as dengue.

Summary of region-specific factors:

- Many people turn to traditional herbal medicines as opposed to seeking medical treatment in a hospital or clinic

- Proliferation of false information about the disease

- Lack of testing and accurate diagnosis to provide data to implement effective control methods

- Humanitarian crisis has caused a lack of health facilities and healthcare, and poor living conditions

Peru

The first outbreaks of dengue are believed to have occurred in Peru in 1700, 1818, 1850 and 1876. However, it wasn’t until an outbreak in 1990 that dengue (DENV-1) was confirmed. Since the 1990s the disease has been a persistent threat to the country.

During 2023, Peru suffered its worst outbreak in history and the second highest number of cases in the Americas after Brazil. Towards the end of November 2023, the number of cases in Peru was reported to be 271,279.

In the first two months of 2024, dengue killed more Peruvians than across the whole year of 2023. During this period the PAHO stated that Peru registered the highest fatality rates in South America. This led the Health Minister to declare a state of emergency in 20 regions (out of 25) of the country in February. All four serotypes of the dengue virus have now been detected in circulation in the country.

In Peru, cases tend to increase in connection to the El Niño phenomenon when there is an increase in rainfall, humidity and flooding. El Niño is an irregular climate pattern that describes the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. The warmer waters cause the Pacific jet stream to move south of its neutral position which has a global impact on weather and ecosystems. It tends to occur every two to seven years. During the previous El Niño event in 2017, there were 74,000 cases of dengue reported. The 2023 outbreak was four times more severe.

According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), a combination of El Niño and long-term climate change had a noticeable impact across Latin America and the Caribbean in 2023. Cases of drought, heat, wildfires, extreme rainfall and a record-breaking hurricane caused major impacts on health, food, energy security and economic development. El Niño further exacerbated countries that were still recovering from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In areas of drought and poor infrastructure, water is often collected and stored in tanks that if not properly managed provide breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

In July 2023, Rolf Erik Hönger, area head for Latin America at Roche Pharma stated that: “Chronic underinvestment and a lack of proper health planning have left Peru ill-prepared… Peru has fewer doctors and fewer health professionals per 1000 inhabitants as compared to its South American peers…the frequent turnover of health ministers, who last an average of just four months, further hampers the development of a strategic and data-driven health care system”.

Summary of region-specific factors:

- El Niño phenomenon and Cyclone Yaku brought a deluge of rain to northern Peru during April and May 2023

- Areas of the country suffer from drought and a lack of access to running water leading to people collecting and storing water in containers that can create breeding grounds for mosquitoes

- Inadequate health care system with a lack of stability in policy making

Contributing Factors

The major contributing factors to the spread of dengue are still considered to be the global movement of people and ships, as well as uncontrolled urbanization and absence of sufficient infrastructure and public services, such as water supply, sewers, and waste disposal, leading to informal water collection and storage practices which provide breeding grounds. However, there are many other contributing factors which are constantly evolving.

It is important to understand the life-cycle of the vector and what conditions allow Aedes aegypti to thrive:

- Climate – tropical or subtropical climates with high levels of rain, high temperatures (84F/29C is the thermal optimum for dengue), and low winds create the ideal conditions. Warmer temperatures enhance dengue virus replication within the mosquitoes’ bodies, increases the mosquitoes bite rate and accelerates their reproductive capacity.

- Altitude – they are commonly found in elevations up to 1700m, but have been found over 2100m.

- Breeding ground – shallow, still, fresh, unpolluted water provides the ideal breeding ground for eggs to be laid and larvae to develop.

- Food – male and female adults feed on the nectar of plants.

- Access to blood – female mosquitoes use blood to produce eggs.

- Predators – natural predators to adult mosquitoes include birds, frogs, toads, dragonflies and lizards. Fish, turtles, tadpoles, damselflies (in their aquatic stage) are known to feed on eggs and larvae.

- Habitat and behavior – adult Aedes aegypti live in dark and shaded places and are more active during the day. It is believed adults have a flight range of up to 200m.

- Competition – a decrease in the population of Aedes aegypti has been associated with species competition. In the south-eastern US, the invasion of the Aedes albopictus has had an impact on its population and distribution, although this mosquito also spreads dengue.

© Jeff Attaway

Environmental and anthropogenic factors that benefit Aedes aegypti and increase the chances of a dengue outbreak:

- Urbanization, especially unplanned, densely populated and rapidly booming areas, facilitate the spread of the vector.

- Climate change is leading to increasing temperatures, high rainfall, humidity and flooding.

- Global Warming isleading to more territories becoming habitable to the vector.

- Public health challenges and fragile health systems contribute to the spread, especially during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This also includes a lack of specific training in health care workers.

- A lack of community awareness including a lack of general knowledge, attitudes and practice towards dengue and mosquito control hampers prevention and management efforts.

- Migration, mass movement and Industries that promote international movement such as shipping distribution and tourism spread the disease.

- El Niño phenomenon

- Political and financial instability put stresses on systems of management, infrastructure and healthcare systems.

- Humanitarian crises such as conflict or natural disasters put a countries’ health care system and infrastructure under stress.

- Poor infrastructure of water and sanitation creates breeding grounds for the vector. Poor transportation systems create geographical barriers and a lack of access to health facilities.

- A lack of natural immunity within a population, especially in previously dengue naïve countries and countries that have multiple serotypes in circulation leaves people vulnerable to the disease.

- Plastic waste is known to be the perfect breeding ground as it collects and holds water. Many of the worst hit countries do not have adequate recycling and waste management systems and also buy plastic waste from other countries.

Along with biological factors that are believed to increase the chances of someone getting dengue (age and pre-existing health conditions), it is believed that there are also socioeconomic and behavioral factors related to dengue cases too. Individual and social dimensions include the level of education, income, living conditions, care seeking behavior and culture. However, more data and studies are required into these demographic variables.

There are also occupations that make people more vulnerable to dengue such as farmers, laborers and merchants due to their exposure working outside during the day in environments favorable to the vector. Healthcare workers based in areas where the disease is prevalent are also at risk.

Economic Consequences on a Global Scale

Dengue outbreaks are often abrupt and impose an enormous socio-economic burden on households, healthcare systems, and societies. Estimating the costs of the disease is important for helping policymakers and public health officials allocate resources and create productive prevention and control interventions. Back in 2016, the estimated global economic burden of dengue was US$8.9 billion per year.

In 2023, a cost-of-illness study was published using data collected from patients hospitalized from confirmed dengue over the whole of 2019. The study was conducted in two private and two public hospitals in urban Dhaka, Bangladesh. The purpose of the study was to assess the economic impact the disease had on the country. The findings showed that the average cost to society for a person with a dengue episode was $479.02. The cost burden was found to be significantly higher for the poorest households. The study was performed from the societal perspective which considers all types of costs, regardless of who incurred them – and considers both direct and indirect costs.

Direct costs to a household are defined expenditures during the period of treatment which includes both medical and non-medical costs; such as transportation to the medical facility, lodging, and food. Direct costs to a health care system can include diagnosis, laboratory, medicine, feeding, and other institutional costs connected to treating the patient.

Indirect costs consider income loss due to absence from work and the productivity loss that reflects the value of unpaid time devoted to caregiving (from family members for example).

Other countries and regions have done similar studies. Ten years ago, the estimated annual economic burden of dengue in 12 countries of Southeast Asia was $950 million. A report published in 2023 used data collected over 2019 to assess the economic burden of dengue in the Zhejiang Province, China. The total economic burden per case including both direct and indirect costs was calculated at $543,213. To keep on top of the estimated costs per country, region and globally, regular economic studies are required.

If the current factors that are driving the outbreaks, such as climate change, global warming, and urbanization, continue and if drastic prevention and control methods are not implemented – these projected costs are likely to increase.

By

By