Dona Dora’s man is away from home a lot more these days. It didn’t used to be like that.

He leaves early, sometimes on foot, but increasingly on his bicycle, and heads into the forests surrounding Belém, the capital of Brazil’s Para province. He keeps his eyes open especially for five medicinal plants that are always in demand — sucuúba (Himatanthus sucuuba), copaíba (Copaifera spp.), andiroba (Carapa guianensis), barbatimão (Stryphnodendron spp.) and pãu d’arco (Tabebuia avellanedae).

Related articles:

Fifteen years earlier, he would have found all five within hours and been back for lunch, but times have changed. These days, medicinal forest plants in high demand are becoming harder to find as forests that have stood strong for millennia are cleared to make way for grazing pastures for millions of cattle, agriculture, and development.

Now, Dona Dora’s man can spend a whole day and not find more than a few plants. It might be late at night before he gets back home.

Dona Dora, meanwhile, will head to her stall in Ver-o-peso, Belém’s long-established riverside market along Guajára Bay, to sell whatever her husband brings back from his forays into the forest. Considered South America’s largest open-air market, Ver-o-peso’s traditional remedies section has 100 or so tightly crammed stalls and curbside vendors selling fresh plant material, tonics, roots, oils and tree barks. The majority of Amazonia’s people trust and prefer forest medicines over Western pharmaceutical products that are expensive and hard to access.

The offerings are diverse, ranging from quixotic, colored concoctions sold in cheap PET bottles such as virility potions, tinctures to make you irresistible to the opposite sex, and even one for detecting if your mate is cheating on you. At the other end are powerful, more expensive forest medicines with therapeutic properties that have been tested and proven in laboratories. A survey of 23 medicinal Belém plant establishments selling 211 medicinal herbs, shrubs and trees found about 45% to be native to the Amazon. Of the twelve leading species whose leaves, fruits, flowers, seeds, barks and exudates were being sold, nine were native to Amazonia. Eight of them existed in primary forests but five were also cut down for timber.

Dona Dora’s customers rely on these forest products to affordably treat a plethora of common and difficult ailments. For example, mastruz (Chenopodium ambrosioides) deals with intestinal worms, while quebra pebra (Phyllanthus niruri) is recommended for kidney and urinary problems. Burns respond well to amor crescido (Portulaca pilosa), which also regrows hair, while nothing works against fatigue and weakness like guaraná (Paullinia cupana). For vaginal infections and other gynecological issues, it’s verônica (Dalbergia subcymosa), and the oil of andiroba is known to treat sprains and rheumatism, repelling insects as a bonus.

Some plant remedies even purport to treat diseases for which Western medicine currently has no cure. Pãu d’arco, for instance, is claimed to arrest the growth of tumors and mitigate gastric ulcers and internal inflammation. Sucuúba derivatives are prescribed against herpes, and marapuãma (Ptychopetalum olacoides) is whispered to be formidable against impotence and diseases of the nervous system. Sacaca (Croton cajucara) is prescribed for diabetes and weight loss.

Of late, times have been hard for Dona Dora, her husband and other plant collectors, as the rich, nurturing forests they depend upon have been receding, some disappearing entirely. Amazon, home to 10% of the planet’s biodiversity, a rich, complex ecosystem that has been stable and resilient over 65 million years of changes, is being battered on several fronts today, some man-made and others natural. Expanding agriculture, and illegal logging and mining erase large swathes of forest. The overwhelming requirements of grazing also level landscapes to create savannahs for fattening millions of cattle whose meat will be served in the kitchens of Europe, the Americas and elsewhere.

Beyond these human depredations, natural forces such as climate change, rising temperatures and unpredictable patterns of rainfall are causing unprecedented droughts and floods, dramatically altering landscapes and habitats, and destroying lives and livelihoods.

However, even as the forests dwindle and diminish, the national and global demand for their medicinal forest plants has been increasing, pushing up prices. Native Amazonian species currently capturing an international market include pãu d’arco, marapuãma, jatobá (Hymenaea courbaril), guaraná, and copaíba.

Copaíba is a big seller. Its oil, locally called “nature’s antibiotic”, has been a staple of traditional medicine across South America for centuries. Bolivian healers use it to cure colds and rheumatism, and two drops daily blended into a tablespoon of honey is still the remedy of choice for bronchitis, tonsillitis and coughs. In Brazil, copaíba oil is applied on tumors and hives to dissolve them, and a tea made from copaíba’s seeds is used both as a purgative and to treat asthma.

Modern medicine recognizes copaíba oil as a cicatrizant (a medicine that promotes scar formation), effective in healing wounds and ulcers, and for treating chronic skin conditions such as dermatitis and psoriasis. Beta-caryophyllene, one of its active ingredients, has potent anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antibacterial and antioxidant properties.

Copaíba oil marketed in Belém today comes from ever-increasing distances because of its naturally low density compounded with scarcity caused by logging. One of Belém’s largest medicinal plant establishments procures its copaíba oil from Amazonas, a neighboring state 745 miles away. Lifelong collectors in Belém will tell you that 15 years ago they could easily find most species of the barks they needed in half a day in secondary forests within 30 miles of the city. Now it takes them an entire day just to find a few specimen plants of each species on their list.

Some other Amazonian medicinal forest plant species whose density has fallen to less than one tree per hectare are jatobá, pau d’arco and tonka beans (Dipteryx odorata).

Understanding what is being lost requires knowing what existed in the first place … but estimating the Amazon’s many plant species has always been a challenge.

Belém, the Amazon, the World

What is happening around Belém is a mirror of the larger destruction taking place across the Amazon basin, covering 2.7 million square miles, of which the world’s largest rainforest accounts for 2.1 million square miles. Though the Amazon stretches across nine countries — Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela — one country has the lion’s share of both the forest and its destruction. About 64% of the Amazon rainforest and 75% of its deforestation belongs to Brazil.

The Amazon under siege

Understanding what is being lost requires knowing what existed in the first place but estimating the Amazon’s many plant species has always been a challenge. Since large areas of this rainforest have never been explored or researched, all estimates of plant species are necessarily hypothetical and can range up to 50,000 depending on which model was used and how the region was defined. However, a more conservative recent study compiled a comprehensive dataset of current Amazonian seed plant species by counting records of actual plant specimens that botanists had collected over centuries of Amazon exploration and kept safe in museums and herbariums across the world. Their verified count of 14,003 species, including flowering plants and palm-like cycads, forms a reliable baseline of the currently known vascular plants of the Amazon. Three-quarters of the Amazon’s identified plant species are believed to be unique to it. All that remains is to enumerate the thousands upon thousands of new species waiting to be discovered and unpack their healing secrets — before they are razed to the ground.

This rich, dense, diverse Amazon has been under human attack since 1978. Tree-cutting used to be the occasional work of subsistence farmers, but in the second half of the 20th century the perpetrators have been industry and large-scale agriculture. In the 40 years between 1978 and 2018, over 290,000 square miles (about 75 million hectares) of this rainforest have been wiped out by deforestation and an estimated 20% of the biome lost. The World Wildlife Fund estimates that at the prevailing rate of deforestation, the Amazon will lose 27% of its biome by 2030.

According to Amazon Conservation’s Monitoring of the Amazon Project, 2022 was the worst year for deforestation, with 7,645 square miles (1.98 million hectares) cleared, a 21% increase over the previous year, caused by cattle ranching, agriculture, mining and road projects in Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela. Powerful corporations and global business interests are involved in clearing forests.

These corporate take-overs of the forest affect about 34 million people like Dona Dora who depend on the rainforest’s plants and other resources to feed, nurture and heal their families, customers and communities. Worldwide, an estimated 4.17 billion people – 95% of all people outside urban areas – live within 3 miles of a forest, and most of them (3.27 billion) live within 0.6 miles. In many tropical countries, these people earn about one-quarter of their income from the forests near them. When a forest disappears, eventually each life it supported is in danger of disappearing too.

Why is the land more important than the trees that stand on it? Since the 1970s, the Amazon’s trees have been mowed down to create grasslands. In just six years, more than 800 million trees have been cleared from the rainforest so that cows can graze. Large-scale cattle farming is by far the Amazon’s — and the world’s — biggest culprit behind massive deforestation, accounting for close to 70% of the forests lost.

Why is it important for cows to graze? Because the world has developed an appetite for Brazilian beef. In a simplification that might sound absurd if it weren’t so true, the Amazon is being razed to the ground so that the world can continue eating burgers.

This is not as far-fetched as it may seem. The beef in fast food chains comes from cattle that have fed on pastures created by cutting down Amazonian tropical forests. The feed given to the chicken in those nuggets and burgers includes soybeans and corn grown in deforested areas.

“Almost every international company that sells meat has some connection to deforestation in their supply chain,” says Glenn Hurowitz, CEO of the campaign group Mighty Earth.

Mighty Earth has used satellite and supply-chain mapping tools to implicate these corporations in the clearing of over a million acres of Amazon forest, an area equivalent to Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands combined.

A planet-wide catastrophe

The Amazon’s disappearing forests are the flag-bearers of an unfolding planet-wide catastrophe that is decimating a treasure trove of potential remedies for existing and future diseases.

Of the 25,791 species known now to be of medicinal use, 5,411 have been assessed under the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, and 723 of them categorized as threatened. Every year, 4,000 new species of plants and fungi are being scientifically described for the first time. Fungi lag behind: only six species of medicinal fungi have been evaluated, and one of them, a wood-inhabiting parasitic fungus called Fomitopsis officinalis, is close to extinction.

It is instructive to look back and see how we got here. After the last Ice Age ended, the planet was a lush paradise of tropical, temperate and arboreal forests. About 57% of the habitable land, or roughly 6 billion hectares, was forested. Change came slowly. Five thousand years passed, but the forested area declined by barely 10%. By 1900, however, in the face of growing population and expanding agriculture, about 1 billion hectares of the world’s forests had been replaced by farmlands.

Then something alarming happened: in just 100 years, humankind destroyed another billion hectares of forest.

Nearly one-third of the planet’s land area has been transformed in the last 60 years, and nearly 90% of deforestation between 2000 and 2018 was related to agriculture. Deforestation has already claimed 1.62 million square miles between 1990 and 2020, at a rate of about 38,600 square miles per year towards the end. Today, forests cover a mere 31% (about 15 million square miles) of the Earth’s habitable surface, and tropical forests cover 60% of all known vascular plant species.

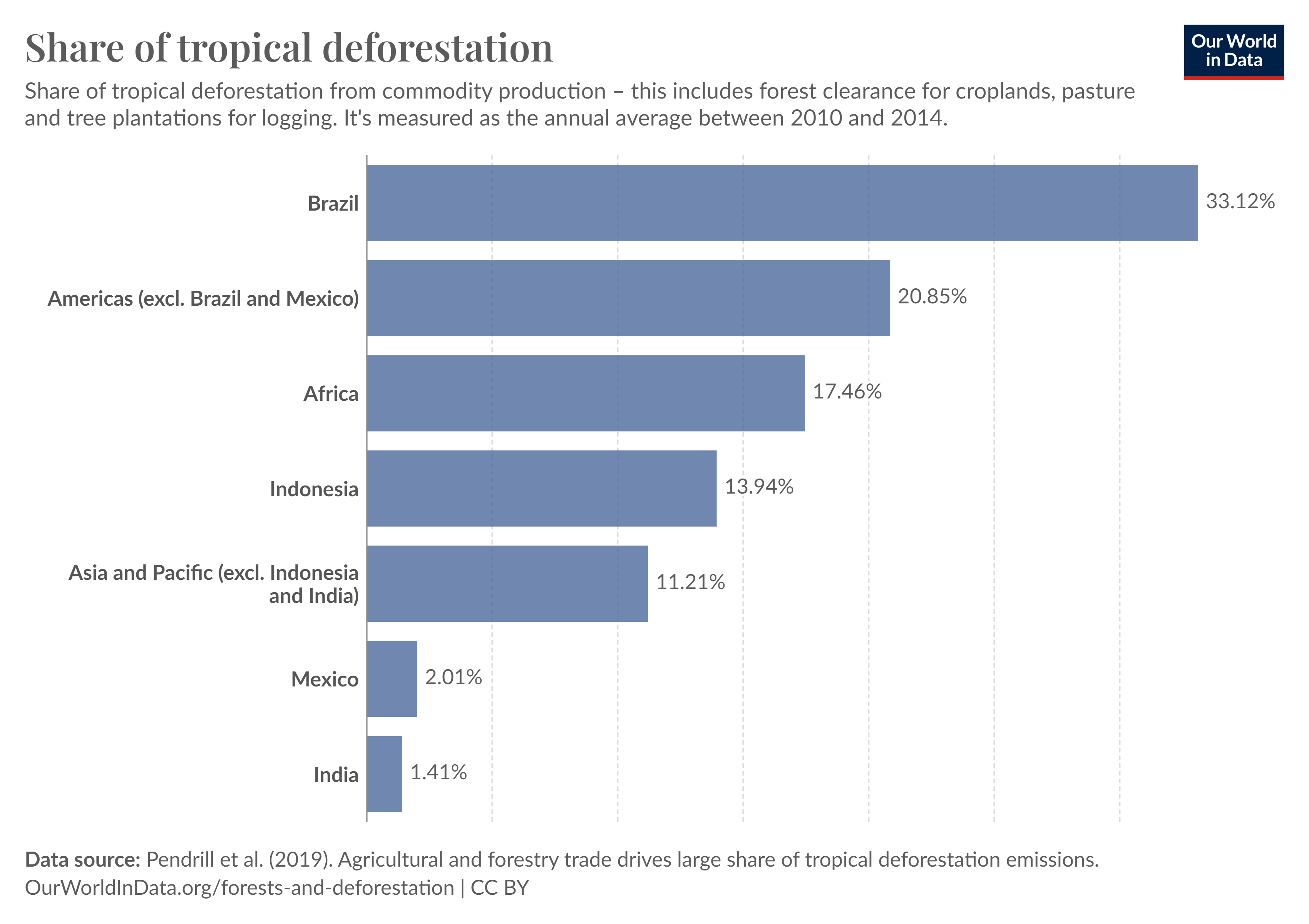

Where is deforestation happening? The startling answer is that only two countries, Brazil and Indonesia, account for nearly half of the world’s deforestation. Estimates based on satellite data indicate that in 2019, the world lost 5.4 million hectares to deforestation, with Brazil and Indonesia accounting for 52% of it. Most of this is due to the expansion of pastures for beef production and croplands for soy and palm oil.

How are we losing forests? The planet has been losing its forest cover in two ways: through outright deforestation, in which all existing trees are completely removed, and the land repurposed for farming, mining, grazing or building cities; and secondly, through forest degradation, where the density of trees is reduced and the canopy becomes thinner but the change is temporary and reversible.

Causes of deforestation

According to a study that classifies forest loss, published in Science in 2019, there are five drivers of deforestation

- Commodity-driven deforestation. This razes forests permanently in order to convert them to other purposes such as agriculture (including oil palm and cattle ranching) or mining. About 26.4% of forest loss can be chalked up to this.

- Urbanization. Here, too, deforestation permanently replaces forests with towns, cities and urban infrastructure such as roads. However, this accounts for a mere 0.6% of forest loss.

- Shifting agriculture. In this, small- or medium-scale subsistence farmers temporarily clear patches of forest for growing crops before moving on to another stretch of forest. The abandoned forests regrow over time. This accounts for another 24% of forest loss.

- Forestry production: Managed, planted forests are periodically logged for products such as timber, paper and pulp. These forests, too, are allowed to regrow before being re-harvested. This activity is responsible for about 26% of forest loss.

- Wildfires. Accounting for about 23% of forest loss, wildfires destroy forests temporarily. Unless the land is converted to other uses, such forests grow back naturally.

Every year, deforestation for commodity production wipes out a forested area the size of Hungary, almost six million hectares, 95% of it in the tropics. The overwhelming proportion of this, 59%, is in Latin America, with Southeast Asia contributing another 28%. One fact stands out: 60% of tropical deforestation is driven by three products for which the world’s demand is skyrocketing — beef, soybean and palm oil.

Ironically, two of these three products are not destined for human dinner tables. Over three-quarters, or 77%, of the world’s soybean production is used to feed pigs, chicken and other poultry, and in aquaculture. Only about 20% of soybeans are consumed directly by humans, most of it as soybean oil. A mere 7% is processed into tofu, soy milk, tempeh and edamame.

However, beef, chicken and other animal meats are farmed exclusively for human consumption. In the simplest terms, human hunger for animal proteins is wiping out centuries-old primary forests. It’s worth digging deeper to ask why humans are eating more animal protein.

One obvious answer is that since there are more humans today than ever before, they’re eating more animal protein than ever before. Population explosion is certainly one of the biggest forces driving the growth of agriculture. For most of human history, the world’s population has been less than a million. There were fewer than 50 million people five millennia ago when forests covered 55% of the planet, and farmlands a mere 1%. After 4,900 years of human civilization, by 1900, that number tripled to 1.65 billion, while forests shrank to 48% and land under agriculture rose to 8%.

However, the next 100 years were catastrophic for the population, which zoomed to 6.1 billion. By 2018, the area under forests was down to just 38%. Agriculture, including grazing pastures, already covers close to 50% of the planet’s habitable land and uses over two-thirds of its fresh water.

The future does not appear promising. The world’s population is projected to hit 9.7 billion people by 2050. In other words, the demand for food can be expected to grow between 35% and 56% in the next 25 years. Producing that food will require agriculture to expand by becoming more extensive as well as intensive, putting even more pressure on forests.

By 2100 the world is expected to be teetering under a population burden of 11 billion people. Feeding them and meeting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal of eradicating hunger would require adding more than a billion hectares of farmland, an area larger than the United States. The result: more forests could be replaced by farmlands. The area under irrigation is expected to double, fertilizer use is expected to go up 2.7-fold, and pesticide use by a factor of 10.

History teaches us that as a person’s income grows, his preference for animal proteins rises proportionately. A person from a low-income country will spend more on staple foods such as cereals. However, as he becomes wealthier, his dietary preferences will shift to include items such as dairy and meat.

Growth in population size and affluence is expected to more than double the demand for all natural resources combined from 92 billion tons in 2017 to 190 billion tons by 2060. Annual biomass extraction is expected to increase from 24 billion tons in 2017 to 44 billion tons by 2060.

The complex, intricate chain of causation between the felling of centuries-old trees and forest plants in some distant rainforest and the hot beef bourguignon mother cooked up today could make the problem feel abstract, making it easy to ignore the impact of a person’s dietary choices on thousands of species of plants, trees, birds, and other animals. Our meals may be hearty, but we are already paying the price in forests lost forever.

Deforestation: A double-edged sword

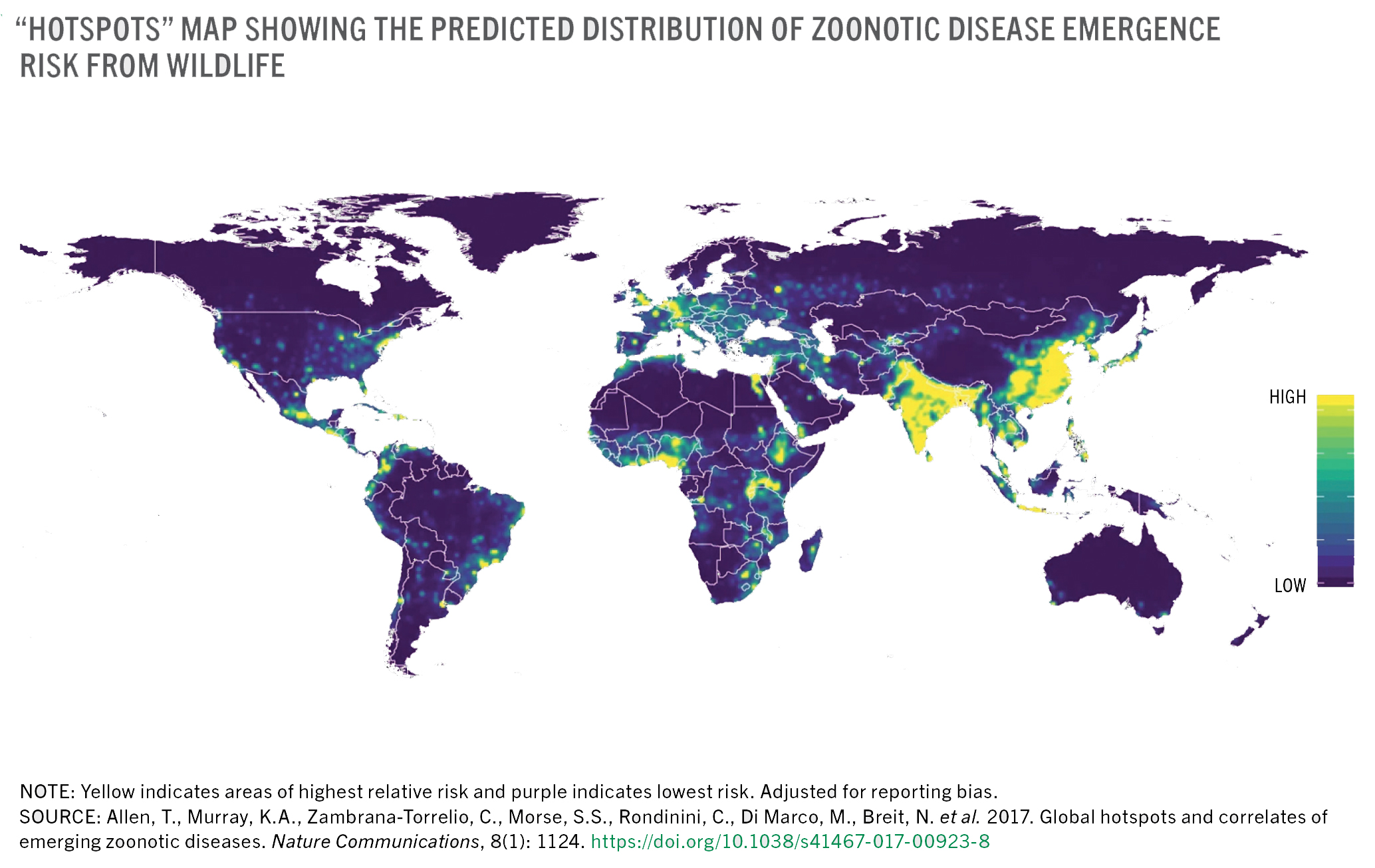

Not only do shrinking forests obliterate the forest plants that make up nature’s medicine chest and possibly hold cures for mankind’s many ills, but they also help set the stage for the emergence of deadly new diseases. Diseases once well contained within the forest’s fauna — known as sylvatic diseases — get released into human environments when deforestation destroys habitats and displaces forest-living creatures, creating conditions perfect for a virus to spill over from animals to human beings. More than 30% of new diseases reported since 1960 are attributed to land-use change, including deforestation, and 15% of 250 or so emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) have been linked to forests. Deforestation, particularly in the tropics, has been associated with an increase in infectious diseases such as yellow fever and malaria.

Arguably, the most fearsome and chilling of recent EIDs was the outbreak of an unprecedented and deadly hemorrhagic fever in Sierra Leone in 2014.

A virus comes to Meliandou

The day after Christmas 2013, the Ebola virus came to an 18-month-old child living with his parents in the village of Meliandou in southeastern Guinea, West Africa. The settlement, with just 31 households and not even a speck on the map, stood in a clearing in the rainforest.

Little Emile Oumanou developed a high fever with vomiting and black stools, and died two days later. His sister Philomene developed the same symptoms and died nine days later. Next to go was his mother, hemorrhaging heavily after aborting her seven-month-old fetus. By then, Emile’s father Etienne had begun to suspect that some ill-wisher had placed a curse on the family.

When Emile’s grandmother Koumba fell ill, she traveled to a hospital at Gueckedou, where she died — but not before infecting nurses, traditional healers and midwives there. The disease, not yet identified as Ebola, went viral through them, spreading like an inkblot over the Forest Region of southeastern Guinea, which shares highly porous borders with Liberia and Sierra Leone. In a matter of weeks, all three countries were reporting cases with the same symptoms and mounting deaths.

The government, mistaking it for cholera, was slow to respond. It was late March 2014 when tests revealed that it was Ebola, a disease unknown at that time in West Africa. By then they were already in the throes of a full-blown epidemic that had killed 50 people in its first three months and would kill 2,535 people over the next three years before being contained in June 2016.

Emile Ouamanou was patient zero, the first infected person to be identified in the 2014 Ebola epidemic. But how had the virus reached the toddler? A team of 17 European and African tropical disease researchers, ecologists and anthropologists interviewed villagers and captured bats and other animals near Meliandou for three weeks. They concluded that migratory fruit bats had brought Ebola to the village.

Meliandou’s children had already found the tree where the bats were nesting. It rose like a giant primordial chimney, towering over the lush rainforest around the village. Its smooth, branchless trunk was a shell, completely hollowed out and as wide as a living room at its base. In it lived hundreds of chittering fruit bats, long known to be flying reservoirs of viruses that cause deadly diseases like rabies, Marburg virus disease, Ebola and SARS.

Since 2000, bats had been inching closer to human settlements as the forest trees they inhabited were felled by logging companies taking advantage of the turmoil and civil unrest in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Mining companies entered the clearings created by logging companies to plunder the exposed earth. Deprived of their natural habitats, bats began seeking new nesting places at the edges of the deforested areas.

Across West Africa, bats are smoked, grilled or cooked in spicy soups and widely relished, but that may not be how the Ebola virus crossed over to humans. More likely, scientists believe, it reached humans through the meat of bush animals such as chimpanzees, forest antelopes, squirrels and others that might have acquired Ebola through bats. When bushmeat hunters sold this deadly meat in local wet markets, they unleashed Ebola into human habitats.

Did deforestation unleash Ebola in West Africa? The answer according to research seems to be: yes. A 2016 study examined forest fragmentation in 11 locations where the Ebola virus is believed to have crossed the species barrier and jumped from animals to humans. Using the CFI (Compound Fragmentation Index), which measures the proportion of the forest at the edges where forested patches interface with cleared areas, they found that all 11 locations had significantly more fragmented forests compared to the overall region in 2014, compared to 2000. The closer they got to the infection centers, the more forest fragmentation they saw.

Guinea is a perfect example of the disturbing nexus between disappearing forests and emerging or re-emerging infectious diseases. The 2014 Ebola epidemic was merely the latest and most sensational outcome of the decades-long pillage of Guinea’s rich forests. Over the preceding decades, deforestation and forest degradation had already laid waste to Guinea’s treasure of forest plants, many of them medicinal and some of them unique to the country. Today, a number of them have gone extinct or stand at the edge of extinction.

“96% of the country’s original forest has already been cleared, and what remains is under severe pressure,” says Dr. Martin Cheek, Senior Research Leader at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. “It looks like as many as 35 species have gone extinct in Guinea, from trees to herbs, daisies, peas and clematis, all due to human pressures. 25 of these are unique to Guinea.”

Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site only five hours drive from Meliandou, has 58 plant species at risk of extinction due to deforestation. Even nearer is the Kounounkan Forest Reserve, which has seven plant species that grow nowhere else on the planet.

At stake within Guinea’s dwindling biodiversity are therapeutic plants long used by traditional healers for a range of acute and chronic conditions. One ethnobotanical research expedition identified 145 plant species in 118 different genera that were in use for treating symptoms of Type 2 diabetes mellitus. An investigation in 2022 found 97 plant species from 85 genera belonging to 43 families that were used for treating hypertension. In yet another study, researchers made 37 visits to Guinea between 2002 and 2005, interviewing 418 traditional healers from 385 villages. They harvested 218 forest medicinal plants from the study and were even able to test some of them in vitro to validate their antibacterial action.

Guinea is not alone. Its story is being repeated all over the world as forests are decimated together with their medicinal treasures and new diseases erupt among humans. We wiped out in 100 years as much forest as was lost in the 4,900 years that preceded it. We are already paying a heavy price in the death toll from emerging infectious diseases (EIDs).

How new diseases emerge

Forests and deforestation by themselves cause neither the emergence of forest-linked infectious diseases nor the global increase in EIDs. Reality is more complex and akin to a series of cascading catastrophes triggered by deforestation or the degradation of existing forests. The human demand for forest products, specifically protein from animal meats, has been spiking as population and affluence increase. Meeting the demand requires both more intensive and more extensive farming, on land that can only be annexed by razing or degrading existing forests.

Faced with the sudden disappearance of their natural sylvatic habitats, the forest’s creatures find new sanctuaries closer to human habitation. As contact between humans and forests reaches unprecedented levels, disease pathogens that were once confined to specific animal hosts within the forest biome see the opportunity to jump to human hosts — and a slew of new diseases begin to emerge.

There’s nothing new about EIDs. One of the earliest recorded was the so-called Justinian plague (Yersinia pestis) of 541 BCE, estimated to have killed 30-50 million people, or roughly half the known world’s population at that time. The same plague virus, known now as the Black Death, took about 50 million lives, or a quarter of the world’s population, in the 1340s. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 60% of known infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, or originating in animals before spilling over into human populations. Also, three out of four EIDs in humans are zoonoses. Of the 250 or so identified EIDs, about 15% show a direct association with forests.

Well-known examples of zoonoses with forest links are –

- HIV/AIDS: Believed to have originated from non-human primates in Central and West Africa.

- Influenza: Various strains, such as H1N1 and H7N9, originate from animals, particularly birds and pigs.

- Rabies: A virus-borne disease transmitted to humans through the bite of infected mammals such as bats, raccoons, coyotes, dogs and monkeys.

- Ebola: First identified in humans near the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of Congo, likely originating from infected bats.

- Lyme disease: A viral disease that infects humans through the bite of infected black-legged ticks that feed on deer and rodents.

Two diseases that have received a second wind from the increased human contact with forests are dengue and yellow fever, both arboreal diseases carried by mosquitoes.

Yellow Fever

A safe and effective vaccine for Yellow Fever (YF), an acute viral hemorrhagic disease, has been available for close to a century, since the 1930s. The virus responsible has remained well-contained within forests in a transmission cycle between arboreal monkeys and sylvatic mosquitoes. However, once deforestation began pushing human settlements closer to forests, the virus began to re-emerge. In the early outbreaks, such as the one in Kenya during 1992-93, the virus did not spread far, staying confined to hunters and forest dwellers who collected fuelwood and water. A much larger outbreak occurred in Sudan in 2005, when armed conflict displaced large populations, pushing some into forests, while others got the virus from soldiers returning from forests.

Since 2016, when an outbreak in Angola spread to the adjacent Democratic Republic of Congo and also China through some returning workers, YF has risen as a major new public threat. The world ran short of YF vaccines — 30 million doses were needed to stop the outbreak — and fractional doses had to be delivered. Later that year, Brazil, which has not seen a YF case since the 1940s, had an outbreak.

In 2017, the multi-partner global Eliminate Yellow Fever Epidemics (EYE) Strategy was established to improve detection, outbreak preparedness, and response. Since then, nearly 250 million people have been vaccinated against YF in Africa. More YF vaccines are available today than ever before, but the disease is far from curbed. In late 2020, confirmed YF outbreaks were reported in Nigeria, Senegal, and Guinea. In 2021 and early 2022, 12 countries across Africa (Cameroon, Chad, Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, and Uganda) reported confirmed YF outbreaks.

Dengue hemorrhagic fever

Like YF in its ecology, dengue was well-contained in its forest niche, circulating in a loop between mosquito vectors and primate hosts. Today it stands as one of the world’s most rapidly emerging diseases, infecting as many as 50 million to 100 million people annually. The dengue-causing pathogen achieved this by adapting to the domestic mosquito Aedes aegypti, and thus becoming endemic in cities and their peri-urban areas, especially in Asia and Latin America. At the time of this writing, Brazil, the country with 60% of the world’s dengue cases, has recorded a doubling of its case count.

The deadliest EID in recent memory is the SARS-COV2 virus, which caused a global pandemic of COVID-19, bringing daily life to a halt across the planet. Although its origins are still under investigation, current evidence such as its genetic similarity to bat-borne coronaviruses strongly indicates that the disease is zoonotic and may have been transmitted to humans from bats through an intermediary wild animal host.

In a world wracked by climate change and warming temperatures, with humans wiping out precious forests with their biomes, COVID-19 is only the precursor of many more unknown, possibly species-threatening new pathogens and pandemics.

Reasons to hope

It’s a good moment to worry. The numbers and facts paint a bleak prospect. However, with the planet threatened by accelerating climate change and biodiversity loss with livelihoods and health at stake, activists, indigenous communities, national governments, NGOs and bilateral organizations have been ratcheting up their response. The range of initiatives, strategies and technologies being deployed to pull the world back from the brink represent the rising tide of a counter-movement. They give hope that forest loss is not a one-way street with an incontrovertible outcome. Five prominent steps in the opposite direction are –

(1) The Convention on Biodiversity

The idea of the countries of the world sitting around a table to address biodiversity first came up as early as 1988 but it took four years more before the world’s nations convened in Nairobi to adopt the text of the first-ever Convention on Biodiversity (CBD). The finalized Convention was thrown open for signing at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992. By the time it went into effect at the end of 1993, it had been signed and ratified by 168 signatories. Since then, a so-called Conference of Parties (COP) has convened every year to discuss issues around biodiversity, decide actions, set targets and pledge their commitments. COP28, held in Dubai last year, included the first Global Stocktake, where signatory states assessed their progress toward the goals of the Paris Agreement and charted a way forward.

(2) Involving indigenous communities

Several studies have shown that when indigenous peoples manage their own traditional lands, the forest thrives and biodiversity flourishes. In Brazil, there was less than 1% deforestation in indigenous community forests from 2000 to 2012, compared with 7% outside them. These forests also contained 36% more carbon per hectare than other areas of the Brazilian Amazon.

A name that comes up when talking about indigenous territorial rights is Dr. Martin von Hildebrand, a nationalized Colombian ethnologist and anthropologist whose sustained and single-minded efforts led to 27 million hectares of Amazon land being titled back to its original indigenous inhabitants. Hildebrand founded Gaias Amazonas in 1990 to work with indigenous people to improve their negotiating skills for expanding their protected territories. This has led to the world’s largest continuous indigenous territory, covering over 27,000 hectares, an area about the size of the United Kingdom.

Robertobra

More research is needed into the methods and processes by which indigenous people reduce deforestation, and whether they are the only agents involved. The strategy has sometimes backfired when certain indigenous tribes in the Amazon who needed money more than forest rights sold their land titles to logging companies and deforestation continued as before.

Also, enforcing indigenous land rights once they have been granted calls for considerable government involvement, as well as a clear mutual understanding of the indigenous people’s responsibilities for the protection of their lands that have been vouchsafed to them.

(3) Afforestation

Not only do degraded forests regrow but as global awareness of the importance of forests increases and nations make commitments to plant new forests, afforestation has created offsets. According to several estimations, global forest loss — a measure of the net change in forest cover, arrived at by any expansion of forest through afforestation to the loss in forests due to deforestation — peaked in the 1980s and has been declining since then. Different sources offer varying but similar estimates. One calculation puts it at 150 million hectares, an area half the size of India, during that decade.

The FAO State of the World’s Forest 1990 report assessed deforestation in tropical ‘developing’ countries to be around 154 million hectares but reckoned that because of the regrowth of old forests, net forest loss was closer to 102 million hectares. The latest UN Forest Resources Assessment estimates that the net loss in forests has declined in the last three decades, from 78 million hectares in the 1990s to 47 million hectares in the 2010s. The area of primary forest has decreased by 81 million hectares since 1990, but the rate of loss more than halved in 2010–2020 compared with the previous decade.

Brazil’s National Space Research Institute (INPE) analyzed satellite imagery to calculate that about 3,500 square miles of rainforest, an area roughly the size of Puerto Rico, had been deforested as of July 2023 — a drop of almost 22% over the previous period, in the year ending July 2023. INPE’s data from its near-real-time deforestation detection system (DETER) indicates that forest clearing in the Amazon has continued to plunge even after July. According to its analysis, accumulated deforestation for 2023 through October was 1,840 square miles, a 50% drop compared to the same period the previous year.

There are reasons to hope that we are seeing a transition and a reversal of trends. For the time being, though, forest biodiversity remains under threat from deforestation and forest degradation and is likely to remain so in the next few decades. We cannot expect biomes that took millennia to evolve to be resuscitated in a few years.

(4) Cataloging new plants and fungi

A major barrier to formulating plans for fighting forest loss is the abysmal lack of knowledge about the world’s plants and fungi. The Kew’s State of the World’s Plants and Fungi 2023 report was a giant milestone in this direction. Drawing on research from 200 scientists across 30 countries, it includes the World Checklist of Vascular Plants. The result of 35 years of work, the checklist is the first-ever catalog of the 350,386 known plant species and their global ranges.

Some key findings that stand out in the report:

- Three in four unknown plant species are at risk of extinction.

- Climate change is having ‘detrimental’ effects on fungi.

- Plants are going extinct 500 times faster than before humans existed.

- The extinction risk has been assessed for just 0.4% of known fungi species.

- Almost 50% of the world’s flowering plant species are under threat of extinction.

However, it is what remains unknown that underscores the urgency of the need to describe and enumerate the remaining plants and fungi. According to a modeling study described in the report, of the 300,000 or so plants yet undocumented, 77% may go extinct before they can be found and studied. “People aren’t taking extinction seriously enough,” says Matilda Brown, lead author of the study and conservation science analyst at Royal Botanical Gardens Kew.

The knowledge gap is an abyss when it comes to the relatively under-researched area of fungi. Of the staggering 2.2–3.8 million fungal species that scientists believe exist, only 148,000 species have been described and named. Importantly, just over 17% (25,611 species) are cultured and publicly available. Of these, barely 0.4% have been assessed for their extinction risk – and half of them were judged to be threatened.

About 10,200 new species of fungi have been formally described since 2020 as new to science. At such a glacial rate of species description, describing them all might require a millennium. However, researchers hope that 50,000 new species could be cataloged each year from environmental samples by focusing on DNA sequencing and molecular assays.

(5) Botanic Gardens and Seed Banks

With two out of five plant species on earth in danger of extinction, preserving the genetic material of plants, whether endangered, extinct or in common use, is becoming an urgent prerogative. The Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC), a CBD program, calls for at least 75% of threatened plant species to be held in collections ex situ – outside their natural habitats – by 2020, including living plants in botanic gardens and seeds stored in seed banks. Today, there are at least 350 botanic gardens and about 1,700 seed banks in 74 countries preserving seeds from 57,051 species, representing 17% of seed plants, over 9,000 taxa globally threatened with extinction and 6,881 tree species.

Among the best-known and most ambitious of the world’s seed vaults is probably Norway’s Svalbard Global Seed Vault, sometimes called the “doomsday vault” or the “Noah’s ark of seeds”. It aims to contain a duplicate of every seed housed in other banks across the globe. Embedded 430 feet within dense rock and permafrost in a remote location halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole, the Svalbard Seed Vault currently houses duplicates of 1,214,827 seed samples from almost every country in the world, with room for millions more.

However, when it comes to forest plants and other wild-growing species, no collection can hold a candle to Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank (MSB), a repository of seeds collected by a global network of partners in more than 95 countries collectively known as the Millennium Seed Bank Partnership. The MSB’s collection has over 2.4 billion seeds from about 40,000 species, including almost all the native plant species of the United Kingdom plus collections from 189 countries and territories. The MSB is the custodian of nearly 16% of the world’s wild plant species, around 10% of which are extinct in the wild, rare or threatened.

What about the predicament of Dona Dora in Belém and others like her all over the world, whose livelihoods are threatened by depleting forests, and health made vulnerable to emerging infectious diseases? One of the most luminous, if still imperfect, demonstrations of a way forward might be the Amazon Soy Moratorium, which showed how a market-driven deforestation initiative that brought together forest dwellers, farmers, suppliers, distributors and giant corporate buyers could decisively end deforestation if implemented with determination.

It started in 2006 with a hard-hitting report by Greenpeace called Eating up the Amazon which, for the first time, exposed how soybean farming in the Amazon had become a sweeping destroyer of rainforests. Everyone was implicated in “forest crime”, from those who grew soybeans and those who bought it from them to sell to fast food restaurants, supermarkets and agribusiness. It was a 4,000-mile soy-lined supply chain that began by clearing virgin Amazon forest and ended in US poultry, pork, and beef feedlots, before landing on American and European dinner plates.

The story named and shamed global players and transnational food corporations. The response was swift and global as corporations and leaders condemned the practice, demanded an end to it and tried to distance themselves from its perpetrators. Many corporations, like McDonald’s and Burger King, roped in big grain traders like Cargill and Bunge in an effort to redeem themselves and began talks with Greenpeace. The result was the Amazon Soy Moratorium (ASM), the world’s first voluntary zero-deforestation agreement in the tropics.

The agreement rested on a simple commitment: companies would no longer buy soy from traders who got their supply from farmers whose soy crops grew on rainforest land cleared after 2006; used slave labor; or threatened indigenous lands through their practices. The results have been both thrilling and cautionary.

The number of new soy plantations based on Amazon rainforest destruction dropped from 30% two years earlier to just 1%. Brazil successfully brought down deforestation by over two-thirds. Amazingly, while deforestation declined precipitously, soy production boomed, growing from 1 million to 3.6 million hectares over a decade. How? They expanded into Brazil’s abundant previously deforested areas and boosted output through more efficient practices.

The soy moratorium is repeatable. Latin America has about 200 million hectares of degraded forest and grasslands, an area equivalent to Mexico, and more than sufficient space to support agricultural expansion as well as ecological restoration initiatives that respect the rights and traditions of indigenous communities.

Of course, not everything went exactly as planned. Some soybean businesses shifted their deforestation efforts to the Cerrado, the second-largest biome in South America and the world’s most biodiverse savannah. Thus bypassing the areas under the soy moratorium, they rapidly decimated large tracts of this biome. The most urgent need today is to extend the soy moratorium to the Cerrado.

Change might come too late for Dona Dora and her husband, for rainforests take many generations to evolve, but perhaps her children’s children will see a forest as lush as their ancestors did.