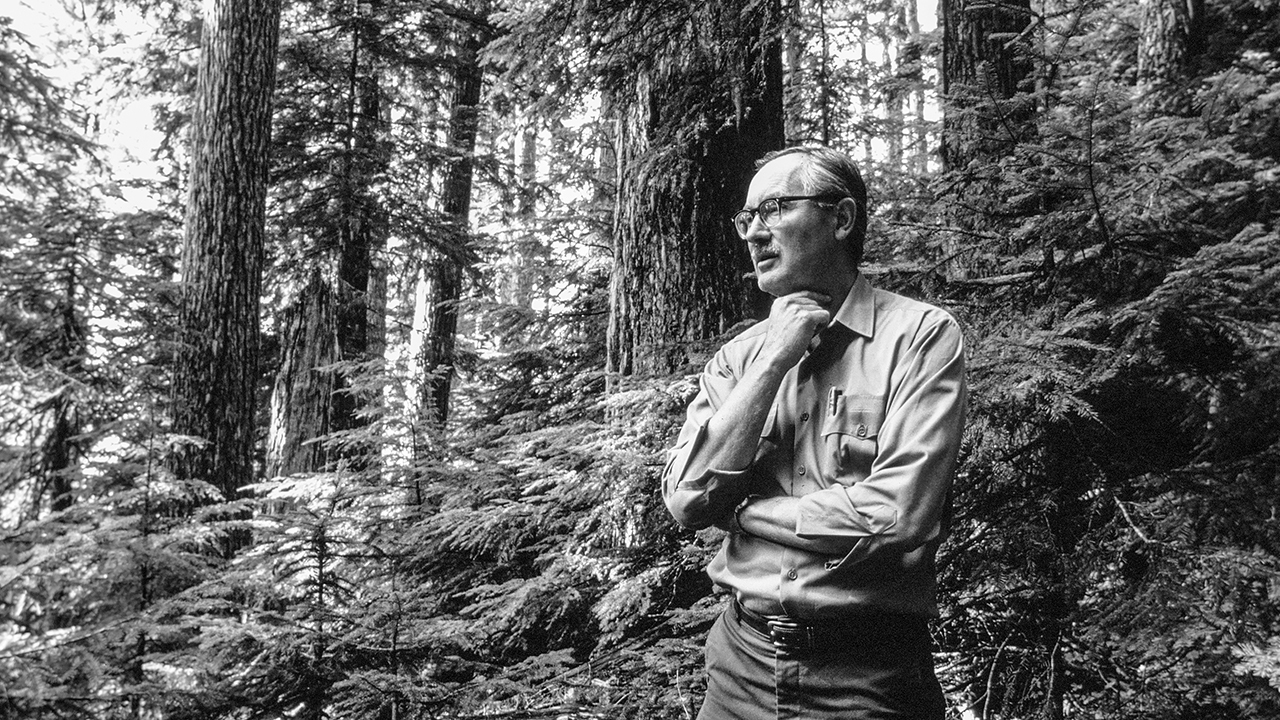

Jerry Franklin, known as the “Father of New Forestry,” has made his mark in forest management for integrating ecological and economic objectives. His approaches, which faced skepticism initially, have become the standard in both environmental and timber industry circles.

University of Washington

Franklin began his career as a research forester for the USDA Forest Service in 1959. His early work included long-term experiments on forest ecosystems, particularly old-growth forests.

One of Franklin’s significant contributions was his challenge to the practice of clear-cutting. Instead, he promoted “new forestry,” a strategy that involves leaving behind logs, standing dead trees, and some larger live trees to mimic natural disturbances. This approach not only preserves ecological integrity but also supports timber production.

In 1993, he joined a group of scientists in meeting with President Clinton to discuss critical issues related to old-growth forests, logging practices, and endangered species. This collaboration resulted in the Northwest Forest Plan, encompassing 24 million acres of federal land. The plan notably protected old-growth forests and resolved the controversy over the northern spotted owl and timber jobs.

In academia, Franklin has held prestigious positions, including professor of ecosystem analysis at the University of Washington and director of the Wind River Canopy Crane Research Facility. His innovative use of a 250-foot-tall crane has allowed scientists to study forest canopies and their interactions with climate change.

Franklin’s contributions to forest ecology have been recognized with numerous awards, including the Heinz Award for the Environment and the Edward T. LaRoe III Memorial Award for lifetime contributions to conservation biology. His election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences further acknowledges his impact on forest management and conservation.

As a true innovator, Franklin has continued to evolve his thinking. His studies of the Mount St. Helens eruption’s aftermath revealed the critical importance of early seral habitats (scrubby, recently disturbed areas rich in biodiversity). This led him to advocate for management practices that create these habitats, sometimes through targeted logging. While this is controversial to some conservationists, Franklin argues that such approaches can enhance forest resilience and support a broader range of species.

Franklin’s work has had a global reach, influencing forest management practices in places like Scandinavia, Argentina, and Australia. His ongoing involvement in forest policy includes efforts to revise the Northwest Forest Plan to incorporate his latest ecological insights.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this interview are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Public Health Landscape or Valent BioSciences, LLC.