About 287,000 women died during and following pregnancy and childbirth in 2020. Around 95% of these maternal deaths occurred in low and lower middle-income countries and nearly every death was preventable. Equally, children under the age of five continue to face differing chances of survival based on where they are born and raised.

A child born in sub-Saharan Africa is 11 times more likely to die in the first month of life than one born in the region of Australia and New Zealand, and a 15-year-old girl in sub-Saharan Africa is 400 times more likely to die in her lifetime due to issues related to childbirth than a 15-year-old girl living in Australia and New Zealand (with the ratio for SSA being 1 in 40, compared to ANZ being 1 in 16,000 women).

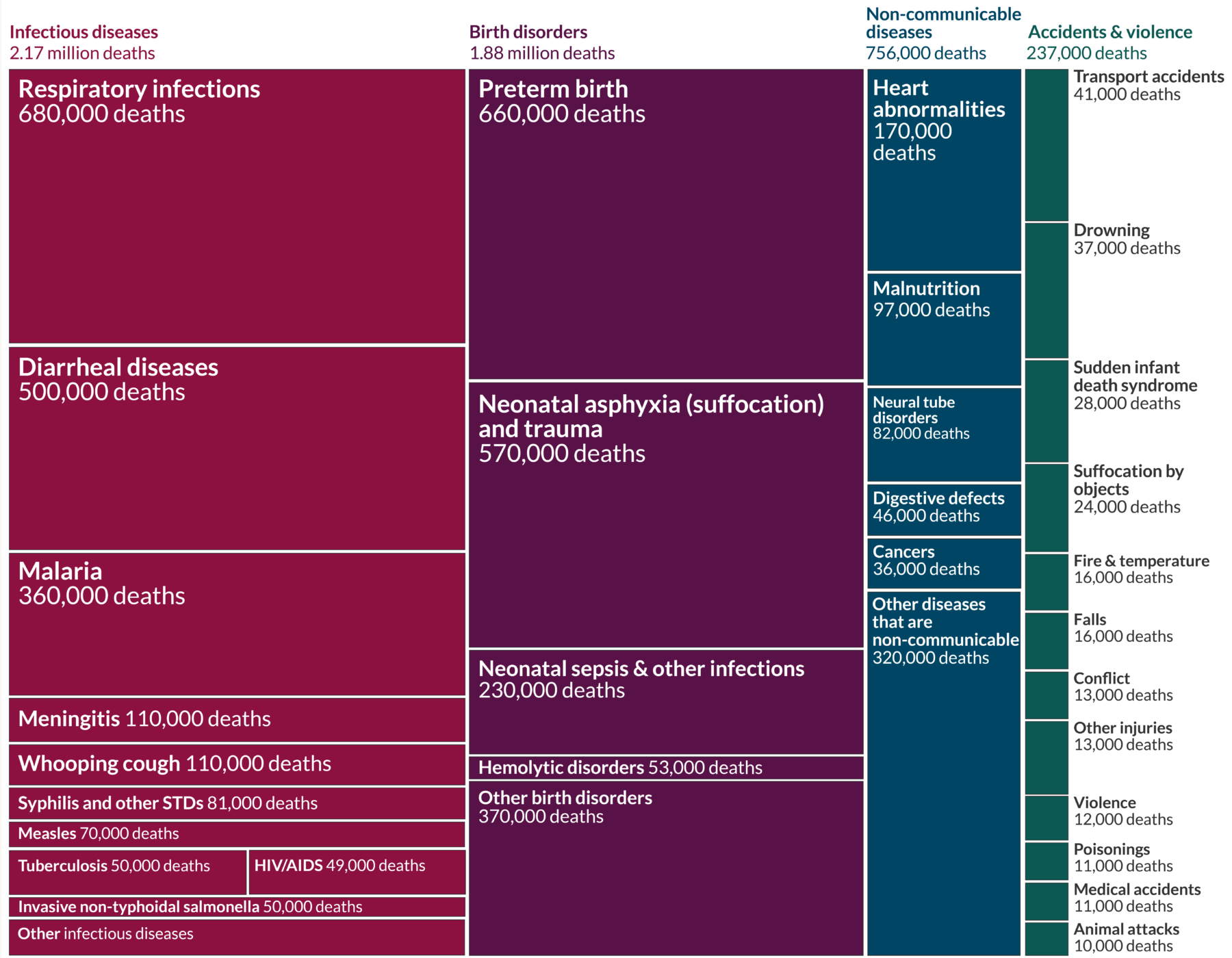

IHME Global Burden of Disease study 2019, Our World in Data, 2019

Data gathered over the last few decades by the United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group (MMEIG), show that some regions are currently missing targets set for goal three of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, especially in regards to maternal and child health. The report also indicates that the health outcomes of mothers and children, in large part, relate to social determinants.

In 2023, the MMEIG published a report that looked at global trends in maternal mortality from 2000 to 2020. The group comprised the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the World Bank Group and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UNDESA/Population Division). The report offers insight into where the global health systems are failing, how and where to invest in fortifying the health workforce with the people, tools and training required to deliver quality care that will make a difference.

To reach the 2030 targets, it’s essential to approach improvements by understanding the challenges and social determinants of each region, country and community, and to conceptualize and deploy bespoke relevant programs of a collaborative nature, thus creating robust changes in health outcomes and to reduce health inequities.

Global Maternal Mortality Rates

The knowledge and practices for preventing maternal deaths have existed for decades, and yet far too many women – across huge swathes of the world – still lack access to these life-saving solutions. The situation is made worse for many communities by the impact of climate change and prolonged conflict, along with over-stretched health systems that lack essential supplies and medicines.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, previous Director-General of the World Health Organization

Maternal deaths are defined as female deaths from any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management during pregnancy and childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy. Any accidental or incidental causes of death are excluded. These figures are usually expressed as the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) which is defined as the number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births. The maternal mortality rate is also used which refers to the number of pregnancy-related deaths in a year divided by the number of women of reproductive age alive that year.

A variety of studies have found that a woman’s risk of death from pregnancy and delivery, where living conditions are harsh, go beyond 42 days. By using the WHO’s standard definition there may be an under-estimation of pregnancy-related mortality Some reports show that by extending the 42 day post-partum threshold up to four months would increase the post-partum pregnancy-related mortality ratio by 40% providing a more accurate picture of the global issue.

Every geographical region and country have different methods of collecting data used to calculate the MMR. Often maternal deaths occur in settings where national registration systems are weak or non-existent. This can make comparing data complicated as sources, reports and surveys are not always thorough or reliable. Some maternal deaths are missed or attributed to other causes. Medical records may be lacking or inaccessible. If an autopsy isn’t carried out there may not always be confirmation that a woman was pregnant at the time of death. There are cases in which pregnancy makes pre-existing conditions worse (such as cardiovascular diseases and HIV) and indirectly causes a woman’s death. There can also be social, cultural or legal issues around reporting whether women were pregnant when they died.

In cases where reliable data is not available, model-based estimates are used. For example, one method that has been used to obtain missing data in rural communities in Kebbi State, North-West Nigeria, is the ‘sisterhood method’. In this method maternal mortality numbers are calculated by surveying women and asking them about their sisters. By surveying 2917 women information was obtained on a further 8233 female siblings, 409 of whom had died and 204 (49.8%) were classified as maternal deaths. Other possible data sources can include household surveys and a population census.

Another form of measurement that is often used in reports is a woman’s lifetime risk of maternal death. This is the probability that a 15-year-old female will eventually die from a maternal cause. The most recent report presented by the WHO in 2023 found that in high income countries, this probability is 1 in 5300 females, but in low-income countries the risk is significantly higher with a probability of 1 in 49. The MMR reflects a similar picture with the 2020 ratio for low-income countries being 430 per 100,000 live births versus 13 per 100,000 live births in high income countries.

In 2020, Nigeria suffered the highest number of maternal deaths with a staggering approximate figure of 82,000. Three other countries hit 10,000 deaths: India (24,000), Democratic Republic of the Congo (22,000) and Ethiopia (10,000). Numbers in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Indonesia, Chad, Kenya and the United Republic of Tanzania were also bad, falling between 5000 and 10,000. Over 2020 the percentage of all maternal deaths that were HIV-related indirect maternal deaths was 10% or greater in South Africa (12.0%), Botswana (11.5%) and Zambia (10.9%).

Central and Southern Asia achieved the greatest overall percentage reduction in MMR between 2000 and 2020 with a reduction of 67.5% and the greatest reduction in lifetime risk during this period with a 79.9% fall, from a risk of 1 in 68 in 2000 to 1 in 339 in 2020. The countries with the largest percentage reduction in the MMR between 2000 and 2020, were: Belarus, Seychelles, Turkmenistan, Romania, Bhutan, Egypt, Estonia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Kazakhstan and Mozambique.

The countries and territories that had significant percentage increases in the MMR between 2000 and 2020 were: Venezuela, Cyprus, Greece, the United States of America, Mauritius, Puerto Rico, Belize and the Dominican Republic.

What are the main causes of maternal deaths?

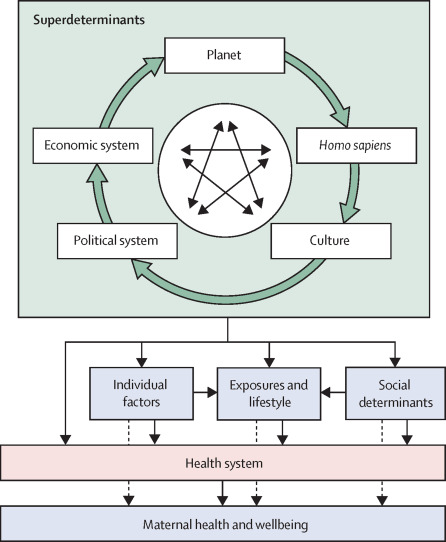

There are many known determinants of maternal health that broadly influence the wellbeing of women before, during, and after pregnancy. Other factors may not be fully recognized or understood due to a lack of research or data in the field.

The Lancet

These determinants can be categorized into the following:

Characteristics of the biosphere – such as the climate and ecosystem

Biological features of the human species – advantages and disadvantages of certain biological features such as the size of a female’s pelvis.

The economic, political, and cultural bases of societies – this can include health insurance policies, health budgetary allocations, health-care policies and legislations on reproductive rights and access to care, societal norms and expectations related to gender roles and cultural beliefs surrounding pregnancy and childbirth.

Which can be further broken down into:

Social determinants of health – the conditions in which women are born, grow and work that cause indirect disparities which could include structural biases related to gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic class.

Individual-level factors – the characteristics specific to each woman such as age, genetics, pre-existing health conditions.

Exposure and lifestyle – the risks a woman is directly exposed to: physical, chemical, biological hazards, infections, and violence.

Dinesh Deokota – licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Medical reasons for death

Women can die either as a result of complications during pregnancy or childbirth or following the birth. Other complications can be a result of existing conditions that are made worse during pregnancy. Many of these complications are preventable or treatable.

The most common causes that account for nearly 75% of global maternal deaths, according to the WHO are:

- Severe bleeding – mostly bleeding after childbirth

- Infections – usually after childbirth

- High blood pressure during pregnancy – pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

- Complications from delivery

Children under five years and neonatal mortality

In 2022, around the world 2.3 million children died in the first 20 days of life (accounting for 47% of deaths in children under 5). Although globally the death rate of children under the age of five years has dropped by approximately 59% since 1990, lower income regions still suffer disproportionately to wealthy regions. In 2022, Sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia accounted for more than 80% of the 4.9 million under-five deaths. It is also worth noting that significantly more babies are born in Africa and Asia. In 2023, 66.25 million babies were born in Asia and around 46 million in Africa compared to 6.34 million in Europe and just over 4 million in north America.

DFID – UK Department for International Development (licensed under CC BY 2.0.)

These deaths that occur in the first month of life are usually associated with a lack of skilled care and treatment during the first vital days of life, causing diseases and other conditions. The leading causes of neonatal death include premature birth, birth complications (birth asphyxia/trauma), neonatal infections and congenital anomalies. The main reasons for the deaths in these two regions due to infectious diseases are predominantly caused by acute respiratory infections, diarrhea and malaria.

During pregnancy and the early years of life are when children are going through the most vulnerable period of their survival. While their bodies are developing rapidly, exposures can lead to long-term health consequences and effects on their brain, respiratory system and immune system.

Unique risks to a fetus: Exposure to environmental hazards (such as extreme temperatures) can interfere with the development of organs, tissues and systems, leading to birth defects and other issues. Harmful chemicals stored within the mother’s body can be passed onto a child during pregnancy and breastfeeding; some known chemicals are mercury and lead. A mother’s exposure to infections, poor diet and inadequate nutrition can impact the development of a fetus.

Unique risks in infancy: As babies and young children breathe, eat, drink and crawl around they are more vulnerable to certain infectious diseases, toxic substances and pollutants in their environments as their immune systems and detoxification mechanisms are not fully developed.

The WHO has identified: air pollution, arsenic, asbestos, benzene, cadmium, dioxin and dioxin-like substances, excess fluoride, lead, mercury and highly hazardous pesticides as major public health concerns.

Infectious diseases that had the biggest impact on children around the world in 2019, in order of most to least deaths estimated, include: respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, malaria, meningitis, whooping cough, syphilis and other STDs, measles, tuberculosis, HIV and salmonella. According to UNICEF the most vulnerable children around the world are those who live in poverty in informal settlements, in undesirable locations such as close to industrial areas or polluted areas with inadequate infrastructure, a lack of clean water and sanitation, without access to education, healthcare and a healthy diet.

Many more risks are created by unique events such as natural disasters and humanitarian crises. According to the 2022 UN Sustainable Development Goals report, widespread disruptions caused in part by the Covid-19 pandemic for example, have derailed progress against many diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. The pandemic also severely disrupted childhood immunization with UNICEF estimating that 67 million children either missed out entirely or partially on routine immunization between 2019 and 2021. Diseases such as cholera, measles and polio are now reappearing in countries where they had previously been controlled.

DFID – UK Department for International Development, January 2017, (licensed under CC BY 2.0.)

A breakdown of key social determinants

By analyzing data in connection to global maternal and early childhood mortality rates there are key indicators that there are dramatic inequalities between regions and countries which further break down into patterns within each country. These deaths cannot only be attributed to biological differences. Health outcomes are profoundly shaped and influenced by social dynamics related to how societies are structured and governed: the social, economic and cultural environment, and an individual’s position within a variety of social hierarchies.

In 2008, the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health vowed to raise awareness of how the conditions in which people are born, grow, live and work can determine their health outcome. The United Nations Development Programme further states that interrelated levels of social influence can affect a person’s health outcome including: the community in which they live, the health system available to them, the wider cultural norms, the influence of their family and peers, the legal and policy environment and overarching governance structures.

All over the world there are examples of how political choices and organizations that distribute resources unequally across populations (along divisions of wealth, gender, ethnic background etc) have had a big impact on the health outcome of people within certain demographics. These decisions can cause inequality in a person’s access to information, education, affordable health care or ability to safely and legally abort a pregnancy.

How can mortality rates be reduced and healthcare improved?

In comparing the case studies and available reports, there are many complex social determinants specific to geographic, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inequities that impact the healthcare outcomes of women and children. It is clear that targeted community-based approaches and structural interventions in regards to health, social and economic policy are essential in reducing the inequality shown in maternal and child mortality rates around the world to align with the UN’s third 2030 Sustainable Development Goal.

To address maternal health equity in the U.S., the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), identified five essential activities for the integration of social needs into health care: (1) awareness, (2) adjustment, (3) assistance, (4) alignment, and (5) advocacy . A workshop carried out in 2021 brought together a variety of experts to discuss the MMR in the country and the clear racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities.

Joia Crear-Perry from the National Birth Equity Collaborative, stated in a presentation that “achieving reproductive justice requires an analysis of power systems, addressing intersecting oppressions, centering of the most marginalized, and joining together across issues and identities.” Crear-Perry also explained that while it is important to address the SDOH, “if we do not undo these root causes [institutional racism, class oppression, and gender discrimination] , we will make programs around these social determinants of health, but not undo the harm, the root injury that caused them in the first place. ”

A second speaker, Monica McLemore from the University of California, who was involved in the Giving Voice to Mothers study, stated that through her research they found that women of color were more prone to receiving disrespectful care and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth. One in six mothers report experiencing one or more types of mistreatment, including being shouted at, scolded, threatened, being ignored, refused, or receive no responses to requests for help . To build trust in the healthcare system these attitudes need to be addressed and patient care improved.

What was clear from the NASEM workshop is that accurate data must be collected on a global, national, and local level but that also includes surveying, gathering data and listening to the women who are identified within the demographics that are worse affected by poor MMR to understand the SDOH and uncover root causes so policy makers are better informed and resources can be effectively allocated.

In 2017, the Nigeria Minister of Health inaugurated the 34-member ‘Task Force on Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Nigeria’, which has called for high-level, persistent political commitment; predictable disbursement of financial resources and sustained unwavering focus on implementation compounded by human resource challenges . The Task Force recognized that it was imperative for there to be collaboration between the government and stakeholders, including community and traditional leaders at all levels .

Once SDOH are clearly identified, interventions are required to target the causes and offer vital support systems, often these approaches occur outside the health sector. The United Nations Development Programme states that this may include peer counseling to provide social support to individual women while cash transfers or participatory women’s groups help address economic marginalization and build social capital at community level. In many cases legal reforms and policy changes are required to protect women from discrimination and to address gender norms, to give women and girls access to education and economic independence .

By

By