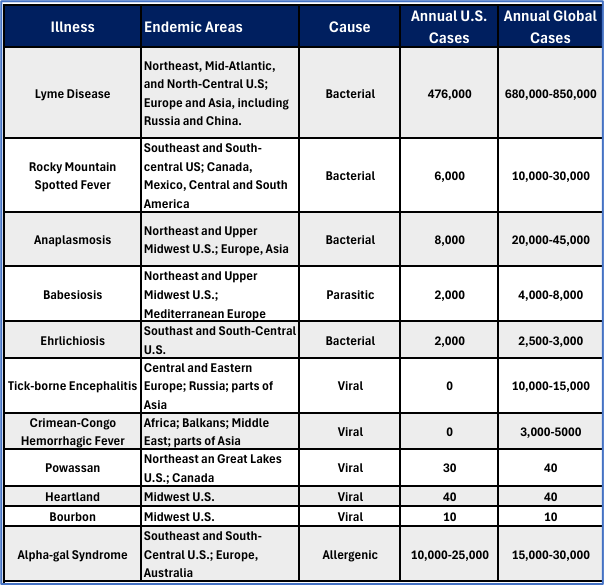

Urbanization, resistance to pesticides, and, most critically, climate change are creating ideal conditions for global tick proliferation. As these 8-legged bloodsuckers expand their territories, the world should expect a corresponding rise in Lyme disease, spotted fever, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, tick-borne encephalitis, and other conditions that infect humans, pets, and livestock.

“This is an epidemic in slow motion,” a Centers for Disease Control (CDC) tick expert and research, biologist told the Associated Press.

Ticks live on every continent except Antarctica, and while estimates of annual tick populations vary, the scientific community agrees that their numbers are growing. Researchers also are unanimous that arachnids pose an increasing health risk as mild winters and longer summers associated with global warming kill off fewer individuals, give them longer to develop and feed, and make higher elevations and northerly latitudes that previously were too intemperate or elevated more hospitable.

Tick Populations Reaching a Tipping Point

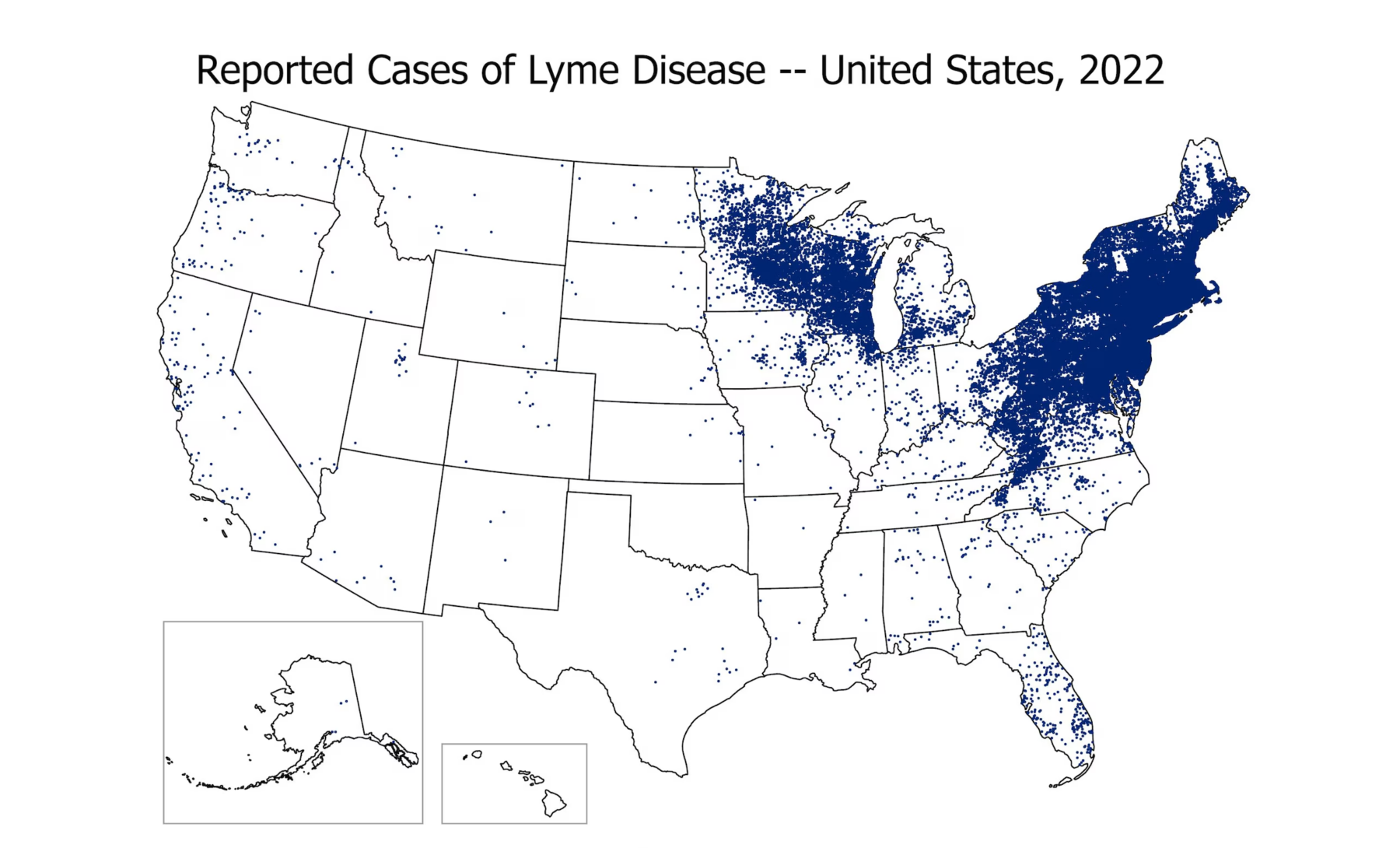

In the United States, “an increasing variety of ticks are pushing into new geographical areas, bringing unusual diseases.” Species once isolated in southern climes like the Gulf Coast tick and the Lone Star tick are now being detected as far north as New York. Of more immediate concern from a public health perspective in the U.S. is the Lyme disease-carrying common blacklegged, or deer, tick.

Once pervasive in the wooded areas of the eastern half of the country, blacklegged tick populations fell off as industrious pioneers and settlers ventured westward, culling deer for food and clearing forests to make room for farms, factories, and settlements. Conservation efforts have preserved forests and revived deer populations, and while wooded suburban backyards increase opportunities for humans, deer, and the ticks they harbor to cross paths, this also raises the risk of interactions. These ticks can now be found not only in the Great Lakes and New England regions, but through the South and the Great Plains.

Tick proliferation is not only a U.S. concern, however.

With much of Canada’s population living in suburban and rural communities that abut wildlife habitat, they encounter more the small mammals on which many tick species feed. “They’re coming into the interface where the likelihood of tick exposure is high,” explained Dr. Gerald Evans, chair of the Division of Infectious Diseases and professor of medicine at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. Higher temperatures, he said, have enabled “established reservoirs for a lot of these pathogens.”

Only 144 cases of Lyme disease were cataloged in Canada in 2009. At least ten times as many have been recorded every year since 2017, including over 2,500 for three years in a row.

A recent study found the first instance of Tacheng Tick Virus 1 carriers in Europe. The ticks were collected in Poland, far from their “home” territory in Kazakhstan and northern China.

“Overall, we observed an expansion of newly documented pathogenic tick-borne viruses into Europe,” the study’s authors reported. “The overall prevalence of tick-borne infections is increasing globally…[T]ick-borne infections may produce a significant disease burden on local healthcare providers and constitute an eminent public health threat.”

Farther south in Europe, the healthcare burden further manifests. Annual Lyme disease cases in France has nearly doubled from 26,000 to almost 50,000 since 2009. The reasons are familiar, said the Pasteur Institute’s Eva Krupa, who researches the emergence of arthropod-borne pathogens:

The geographical distribution of several tick species is changing, and in Europe ticks can now be found in new environments, including at higher altitudes because of rising temperatures and in urban and peri-urban green areas. This increasingly brings tick populations into contact with people who are not aware of the risks they represent, especially on routes through green areas that are popular not only with walkers but also with animals, which themselves can be reservoirs for pathogens.

Even in equatorial Africa there has been an increase in the incidence of tick-borne relapsing fever. Climatic conditions here were already conducive to large tick populations, so global warming is not to blame. Other factors, most notably, increased opportunities for human/tick contact, deforestation, drought pathogen evolution, and ticks’ ability to quickly develop immunities to acaricides, are at work.

Whatever the reasons, the African hut tampan, a type of soft tick that carries relapsing fever, has expanded its territory more than 350 kilometers from Senegal to Morocco over the last 50 years.

Tick Tock: The Race Against Lyme Disease

Tick-borne diseases are vastly underreported, according to most health agencies. Just over 63,000 cases of Lyme disease were reported in 2022, More than double the number from 2004. Yet the CDC estimates that as many as 476,000 people may actually be diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease each year in the United States.

It is by far the most widespread tick-borne disease in the U.S. and around the world. According to an analysis of blood antibodies, more than 1/7 of the world’s population has been infected with Lyme disease.

Though it was only first diagnosed in the U.S. in 1976, after several people in and around Lyme, CT, became ill with swollen joints, chronic fatigue, and a persistent rash; Lyme disease is one of the fastest-growing vector-borne infections in the country – with most cases still concentrated around New England and the Mid-Atlantic states. The most recent data puts Pennsylvania at the epicenter, with more than 29% of reported cases. The Keystone State – along with New York and New Jersey – account for more than half the reported Lyme disease infections. Maine, Vermont, and Rhode Island report the highest instances per capita, but the upper Midwest also experiences numerous outbreaks and every year cases are reported in every state except Hawaii.

Reporting is more consistent in Europe, where the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) documented more than 150,000 confirmed Lyme disease in 2017, a 77% increase from 2012’s 85,000 cases

The bacterial infection is also endemic to parts of the United Kingdom and much of central Europe Austria, southern Germany, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia register the highest diagnosis rates.

Lyme disease almost always presents first as a small bump and skin rash. After a few days, the rash may grow to a circular shape with a patch in the middle. This Erythema migrans, or bullseye rash, is usually not painful or itchy and not everyone develops this telltale sign of Lyme disease. Patients may also experience fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, chills, fatigue, and swollen lymph nodes.

Lyme disease must be treated promptly to avoid more serious conditions within days or weeks: meningitis, skin lesions, heart arrythmia, dizziness, and Bell’s palsy. Many of Lyme’s disease symptoms will disappear with proper medical care, but if left untreated may lead to arthritis, tingling extremities, short-term memory loss, and other chronic conditions.

James Gathany, 2007

Other Diseases Ticking Up

Lyme disease often dominates the conversation about tick-borne illnesses, but it’s far from the only threat these blood-sucking parasites pose. A growing body of research reveals a complex ecosystem of pathogens transmitted by ticks, each with its own vectors, symptoms, endemic regions, and potential complications.

Lesser-known and less prevalent, but equally burdensome and unhealthy, these infections include the potentially fatal Powassan virus, persistent ehrlichiosis, and emerging threats like the Heartland and Bourbon viruses. Some of these illnesses thrive in the developing world, increasing the urgency in understanding their impact.

Spotted Fevers

Caused by varieties of the Rickettsia bacteria, these diseases are named for the regions in which they were identified or have become endemic:

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever: The most severe of the spotted fevers, RMSF was first identified in Montana and Idaho in the early 19th century. Most current cases, however, are reported in the South. North Carolina, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Missouri account for more than half of domestic cases, with the infection spreading across the country and into Mexico and Central and South America.

- Mediterranean Spotted Fever: Still primarily found in the region for which it is named, the disease, also referred to as boutonneuse (French for “spotty”) fever because of the unique rash it forms, is found in North Africa, southern Europe, and parts of the Middle East. Like RMSF, American dog ticks and brown dog ticks are responsible for its spread.

- African Tick-Bite Fever (ATBF): Common in rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of the Caribbean. ATBF is the least severe of the spotted fevers. Most cases are found in people who visit endemic areas, as local populations have developed a partial immunity. African bont (Kaiser) ticks and southern cattle (Texas fever) ticks, which usually feed on cattle, horses, and deer, also transmit the fever to humans.

Oleg Mediannikov

Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

Believed to infect tens of thousands of people annually, CCHF is dispersed across vast swaths of Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East, Türkiye, Iran, Pakistan, and the Central Asian republics, as well as Spain and Greece. Ascertaining precise case numbers is difficult owing to limited surveillance and testing resources in significant portions of territories inhabited by the plumose and Nuttall tick vectors.

These limitations also hinder treatment and recovery efforts, as districts regularly report fatality rates of 10% to 40% and occasionally reaching 60%. The disease brings about a sudden onset of high fever and severe bleeding from the nose and gums. This is sometimes followed in rapid succession by multi-organ failure. The severity of the disease depends on several factors, including the viral load, the patient’s overall health, and the timeliness of medical intervention. Fatalities occur about 10 days after symptoms present, due to blood loss or organ failure.

In addition to tick bites, humans can contract the disease by handling infected livestock tissues or blood during butchering or veterinary procedures. The cattle, sheep, and goats on which the vectors typically feed store the virus without becoming sick.

Tick-borne Encephalitis

Occurring in central and eastern Europe, Russia, and northern Asia, TBE progresses to a critical second stage in about 30% of infected persons. Like most tick-borne infections, the initial stage brings mild flu-like symptoms. After these subside, the second stage involves attacks on the central nervous system and development of meningitis or encephalitis, high fever, severe headaches, neck stiffness, and even seizures and paralysis. The most critical cases lead to coma, paralysis, and death. Death rates as high as 40% is reported among those contracting the Far Eastern subtype.

In addition to tick bites, TBE can also be contracted through the consumption of unpasteurized dairy products from infected goats, sheep, and cows.

Tick-borne encephalitis is the only tick-borne disease for which a vaccine exists. Vaccines are recommended for people living in or traveling to endemic areas, particularly those engaging in outdoor activities. Vaccination campaigns in Europe and Russia have significantly reduced the incidence of TBE in these regions.

Anaplasmosis and Ehrlichiosis

Like spotted fevers, these diseases are spread by the rickettsia bacteria, and their symptoms are similar to those of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, though anaplasmosis sufferers usually do not develop a rash. While the similarities in their symptoms often are studied together, they are separate diseases, spread by different vectors, and caused by distinct bacteria. Ehrlichiosis is spread by the Lone Star tick, so it is concentrated in the southern U.S.; while anaplasmosis is endemic to New England, the mid-Atlantic, Great Lakes and West Coast states where its ixodid (hard tick) vectors thrive.

The headaches, muscle aches, nausea, fever, and other flu-like symptoms that accompany an infection appear around two weeks after a bite and dissipate in a few days with proper antibiotic treatments.

Babesiosis

All the other tick-borne diseases are either bacterial or viral. Babesiosis is the only one caused by a parasite. When introduced to the body through a tick bite (the blacklegged, or deer tick again is the most common culprit, making the Midwest and Northeast U.S. the most susceptible regions) the parasite attacks red blood cells. When it destroys erythrocytes faster than they can be replaced, patients can develop hemolytic anemia. Most people infected with babesiosis either experience no symptoms or develop the flu-like conditions common in other tick-borne diseases: headache, chills, fever, nausea, and fatigue. If treatment is required, combination drug therapy has proven effective.

Babesiosis can become serious and even life-threatening for older patients, those with compromised immune systems, liver or kidney disease, and people who have undergone splenectomies.

Alpha-gal syndrome

Perhaps the strangest illness caused by tick bites, alpha-gal syndrome triggers allergic reactions to red meat. Prevalent in the southern U.S. where it is transmitted by the lone star tick, the condition makes people allergic to a sugar found in beef, pork, lamb, venison, rabbit, goat, and most other mammals (it does not occur naturally in humans). In other parts of the world, the disease may be transmitted by the deer tick, cayenne tick (Central America) and Asian longhorned tick. Food, medicines, and personal care products such as milk, gelatin, and some soaps contain alpha-gal.

The allergic reaction usually manifests a few hours after people with the syndrome eat mammalian meat. They develop itchy rashes, nausea, and headaches. Severe cases may send sufferers into anaphylactic shock. Most times, however, the condition subsides as long as people with the condition avoid red meat.

Bourbon and Heartland Viruses

Recently discovered in Missouri and Bourbon County, Kansas, these viruses are also transmitted by the lone star tick. While no treatment exists, heartland virus symptoms are mild; Bourbon virus is rarer but can become severe. The first reported case resulted in the patient’s death. Fewer than 100 combined cases have been reported.

Powassan Virus

Another rare but potentially severe tick-borne illness named for the Ontario town where it was first identified in 1958, Powassan is related to West Nile virus and is transmitted by blacklegged, groundhog, and squirrel ticks that become infected by feeding on small and medium-sized mammals. Unlike other tick-borne diseases like Lyme disease, which typically require the tick to be attached for more than a day for pathogen transmission, POWV can be transmitted in as little as 15 minutes of tick attachment.

The virus is endemic to the northeastern and north-central United States, as well as southeastern Canada. Cases have been reported in states such as Minnesota, Wisconsin, New York, and Maine.

Powassan virus symptoms can appear from one week to one month after the bite. Severe cases can cause encephalitis or meningitis characterized by fever, headache, vomiting, weakness, confusion, loss of coordination, speech difficulties, and seizures. There is no treatment, only comfort care such as IV fluids and respiratory support. About 10% of the people experiencing these symptoms die, while half the survivors develop long-term neurological aftereffects.

Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment

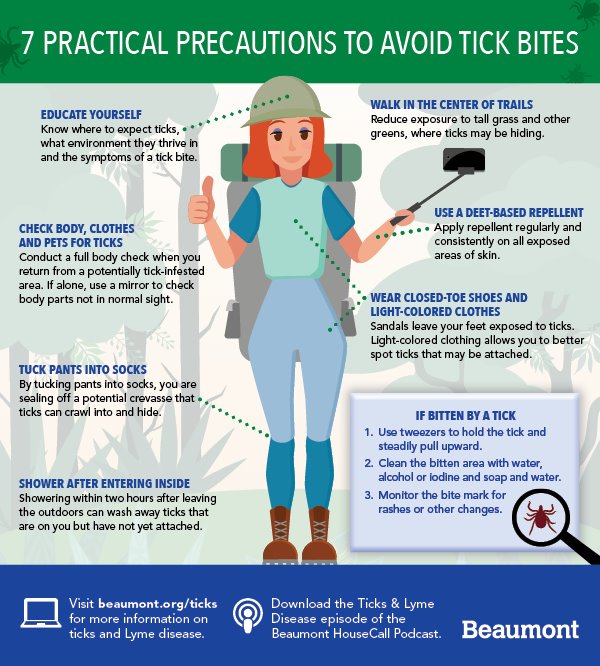

With warmer global temperatures, ticks remain alive and active for longer periods in more diverse climates than ever before. Regions previously immune to tick-borne diseases now find themselves in the epicenter. It is critical that people living, recreating, and working in new and existent tick habitats educate themselves on how to prevent, recognize, and treat these potentially rampant illnesses.

Vigilance must be maintained year-round, supported by robust and adaptable public health campaigns. Environmental management strategies must evolve to accommodate shifting tick habitats and to mitigate the risks associated with their spread.

Prevention: The First Line of Defense

Only one tick-borne disease can be controlled through vaccination, so the key to prevention lies in protecting ourselves from tick bites. When camping or hiking in tick-prone areas, wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants tucked into socks to limit the amount of skin exposure. Apply EPA-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus, para-menthane-diol, or 2-undecanone. Boots, tents, sleeping bags, and other gear can be sprayed with permethrin to repel ticks for weeks at a time. Take particular care when walking through tall grass and leaf litter. Stay in the middle of hiking trails to avoid brushing against undisturbed tick domains.

After an outing, check yourself, your children, and your pets for any eight-legged stowaways. They like to hitch a ride under the arms, in the ears, in the navel, behind the knees, between the thighs, and on the scalp. Showering soon after an outdoor excursion can limit disease risk.

Treatment: Minimizing the Effects

Depending on the pathogen involved, treatment options vary, but in all cases, early intervention will lessen symptom severity and the likelihood of complications and lasting sequelae. Even when no known treatment regimen has been identified, supportive care can manage symptoms and reduce discomfort. Seeking a doctor’s care also allows medical professionals to monitor the disease’s progression, note symptomatic and behavioral changes, and adapt care accordingly.

It’s important to note that while antibiotics are effective for bacterial tick-borne diseases, they are not appropriate for all. For instance, viruses transmitted by ticks do not respond to antibiotics and may require different management approaches.

Diagnosis: Challenges and Complexities:

With unique characteristics, tick-borne diseases often defy accurate diagnosis and identification. Expanding the knowledge bank is critical for both medical professionals and the public to improve diagnostic success and treatment outcomes that are often hindered by a range of factors:

- Inconsistent Presentation: Many tick-borne diseases have multiple symptoms. Not only are they not all present in all patients, but they may also share indications with other illnesses, making them difficult to pin down.

- Unawareness: Patients may not notice when they are bitten by ticks, causing a delay in treatment, and taking tick-borne infections out of primary consideration for the cause of their discomfort.

- Co-infections: Tick species can carry more than one disease-causing bacterium or virus. Contracting two or more pathogens may compound reactions and induce diverse immune-system responses.

- Varied Incubation Periods: The time between a tick bite and the onset of symptoms can vary widely, from a few days to several weeks. Patients may not associate their symptoms with a tick bite that occurred weeks earlier.

- Testing Difficulty: For some tick-borne diseases, like Lyme disease, early tests can be unreliable. The body may not have produced enough antibodies to be detected in the first few weeks of infection.

Tick-borne Diseases: The Economic Bite

The human toll Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses exact cannot be overestimated, but the economic and public policy burden may be just as impactful:

Medical: In the United States, Lyme disease alone is estimated to cost between $345 million and $968 million annually in doctor visits, diagnostic tests, treatments, hospitalizations, and other direct medical expenses. The complexity of diagnosing and treating tick-borne diseases often leads to repeated medical consultations and prolonged treatment courses, further escalating healthcare expenses.

Lost Productivity: People contracting tick-borne illnesses are often bed-bound for several days or weeks. Prolonged absenteeism from work or school delays projects and puts children behind their classmates. Tick-borne diseases can also cause long-term disability, reducing an individual’s ability to contribute to the family’s finances.

Surveillance and Control: Public health organizations’ efforts to monitor tick-borne illnesses and control their outbreak add to the world’s financial burden. Tick- management programs, educational resources, and research into emerging varieties such as heartland and bourbon virus demand significant resources.

Veterinary Services: Tick-borne diseases also affect pets and livestock. Cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs represent a sizable portion of individual and community wealth in large parts of developing Africa and Asia, so the loss of animal productivity and increased animal deaths deal an economic and nutritional blow. Even in the U.S., the cattle industry faces substantial costs due to tick-borne diseases, impacting both small-scale farmers and large agricultural operations.

Conclusion

The alarming rise in global tick-borne illnesses cannot be ignored. The expansion of tick habitats has led directly to the increased incidence of diseases such as Lyme disease, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, and others. Among these factors, climate change stands out as a major driver.

The warming temperatures associated with global climate shifts have expanded the geographical range where ticks can thrive, pushing these vectors into new areas of the northern and western United States, Canada, and even northern Europe. This expansion is not just about ticks moving into previously uninhabitable areas; it’s also about the extension of their active seasons. With shorter winters and longer periods of warm weather, ticks are active for more extended periods each year, thereby increasing the period during which humans can be exposed to tick-borne diseases.

However, climate change is just one piece of the puzzle. Other contributors to the spread of these illnesses include altered land use and urbanization bringing people closer to tick populations. The growth of deer populations in certain areas has provided ticks with ample hosts, facilitating their proliferation and increasing the risk of human exposure.

Social and behavioral trends such as greater participation in outdoor recreational activities, changes in occupational exposures, and landscape designs that bring people into closer contact with tick habitats have all played a role in the rising number of cases.

Finally, access to more sophisticated diagnostic techniques and changes in case reporting have led to a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of tick-borne diseases. Improved detection methods mean that more cases are being identified, contributing to the perception of a rise in these illnesses. Public awareness and education have also played a role, as more people are now knowledgeable about the symptoms and risks associated with tick-borne diseases, leading to increased reporting and diagnosis.

The fight against tick-borne illnesses requires a multi-faceted approach that acknowledges the role of climate change while also considering the myriad other contributing factors.

![]() By Scott Smith

By Scott Smith