Riley Sims, a graduate of Ball State University and currently pursuing her graduate studies at Kent State University, combines geometric precision with spontaneous bursts of vibrant color to create a dynamic representation of life’s complexities, healing and resilience.

A key focus of Sims’ art is her intimate exploration of Lyme disease, a condition she has personally battled. However, Sims’ work goes beyond self-expression – her canvases are powerful advocacy tools. Her paintings education viewers about Lyme disease, bringing awareness to the financial and emotional challenges faced by those with the disease.

Even with her busy school and work schedules, Sims found time to sit down and answer a few questions for us.

The Interview

Q: Can you share some insights into your creative process? How do you approach starting a new piece, from concept to completion?

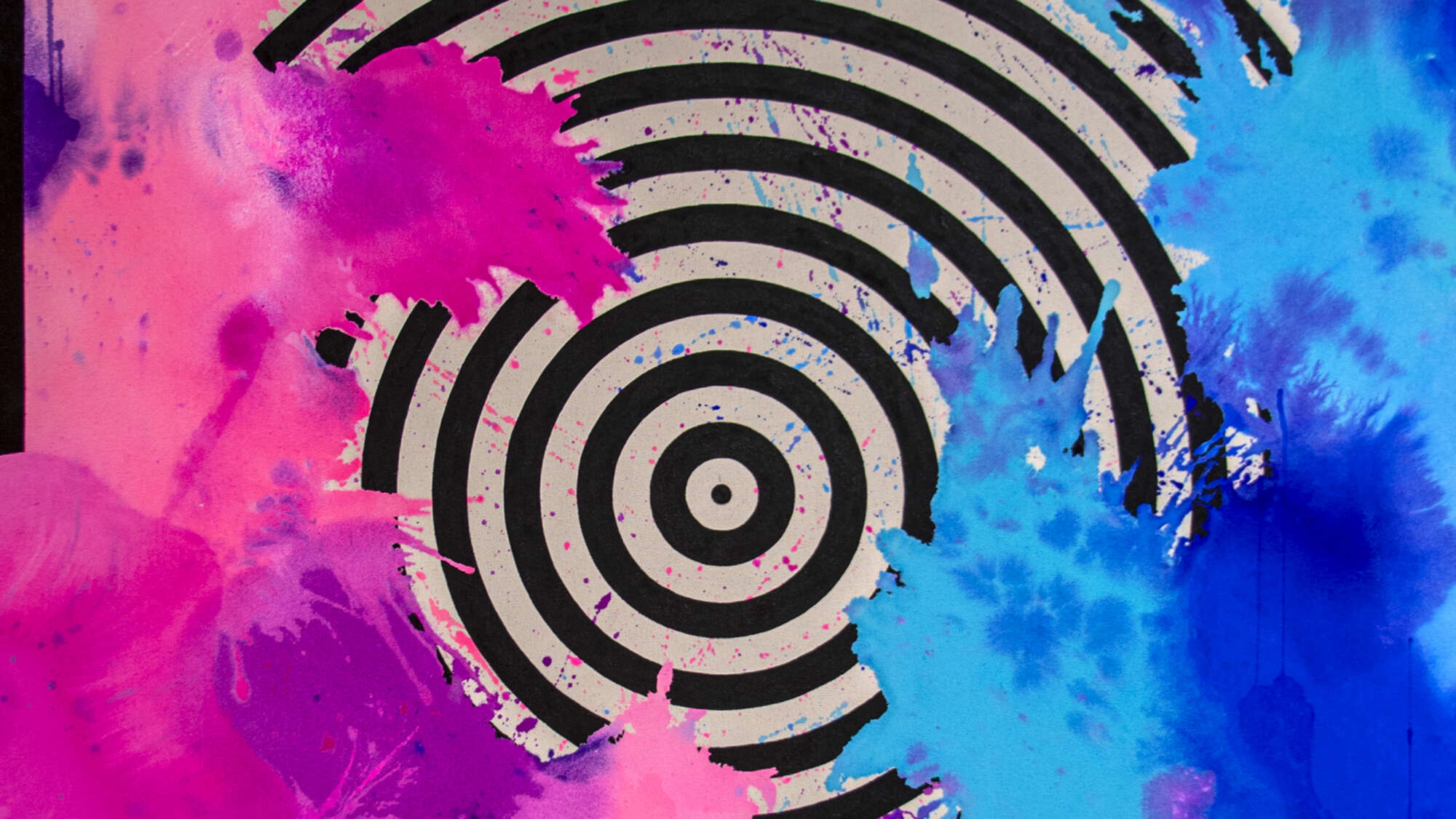

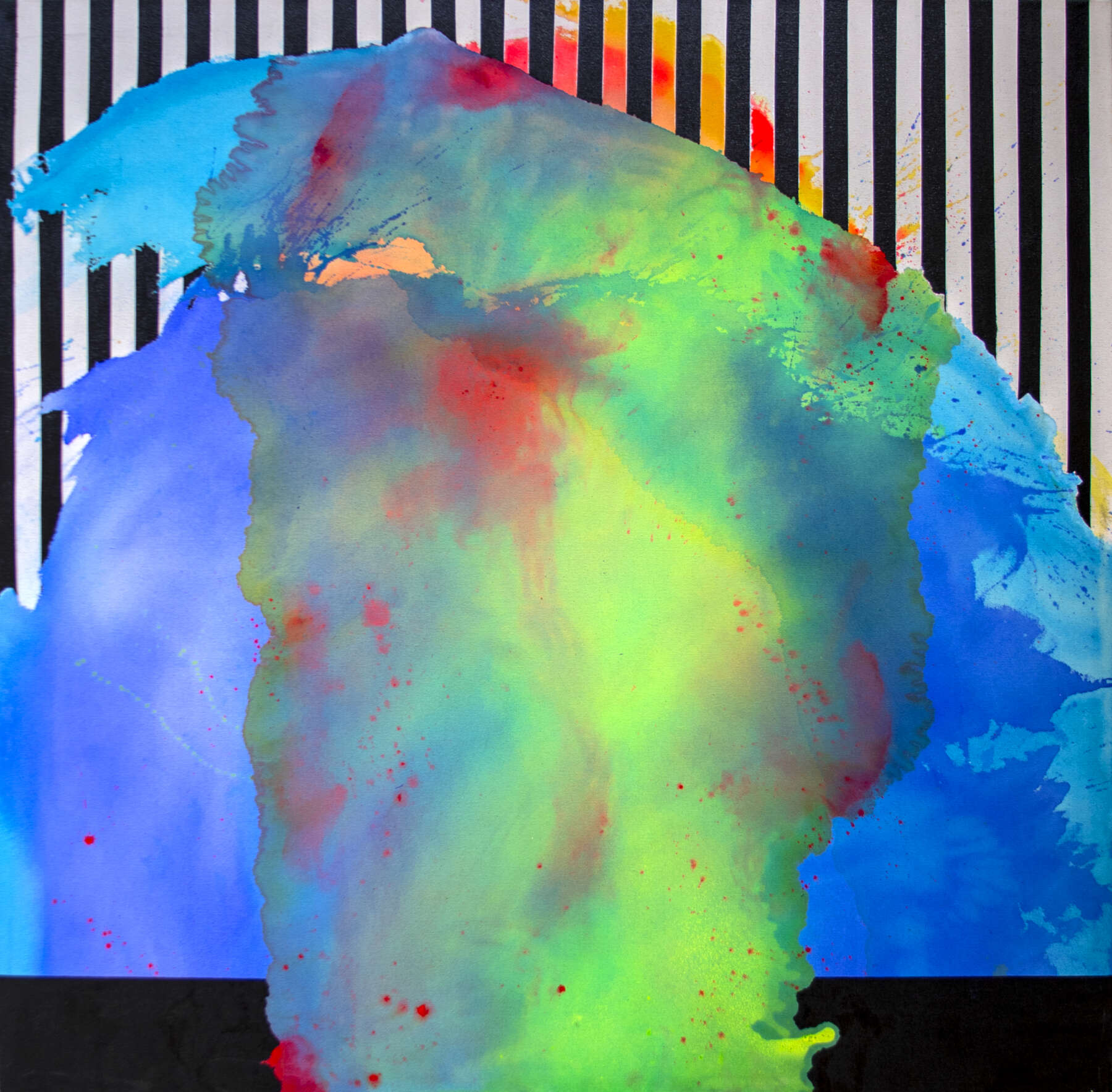

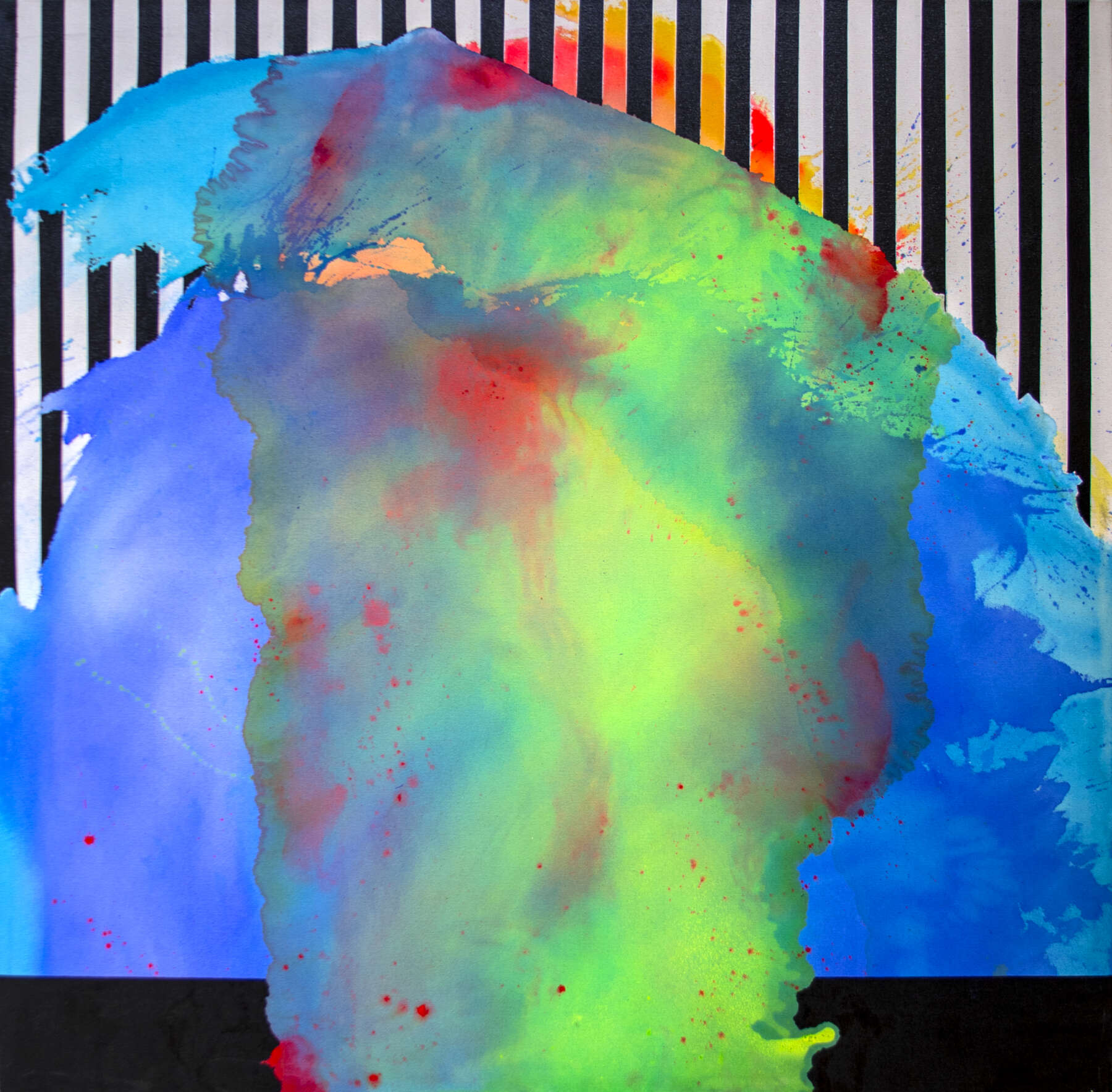

Sims: “When I start a new piece, it often begins with a feeling or frustration I’m dealing with – especially around my experience with Lyme Disease. The unpredictability of life is central to my creative process, so I lean into that sense of spontaneity. I typically work on raw canvas, using a soak-staining technique, where diluted paint seeps into the fibers of the canvas. This creates unpredictable, organic shapes and color spreads that mimic life’s uncertainties and challenges.

After the initial spills dry, I use digital planning to figure out what forms will work best to invade these beautiful, uncontrolled stains. This part of the process is more deliberate – adding geometric shapes or harsher elements on top of the spills represents the limitations that chronic illness, like Lyme disease, imposes on everyday life. It’s the contrast between the free-flowing spills and the intentional shapes that captures the balance I’m trying to explore: the tension between what we can’t control and what we try to control.

Each piece is about finding harmony between these forces, allowing the viewer to feel the unpredictability while also finding structure. It’s a way for me to express the emotional rollercoaster of living with chronic illness while also embracing moments of beauty and joy within the chaos.”

Q: Who or what are your biggest sources of inspiration, and how do they shape the direction of your current projects?

Sims: “When it comes to inspiration, my work is deeply rooted in both personal experiences and the broader collective experiences of the Lyme community. Living with Lyme disease has shaped not only the themes of my work but also how I approach them. A big part of my current project comes from the idea of concealment – how we, as Lyme patients, often hide what’s really going on. Every time we try to show the truth, it’s either shut down or dismissed, especially by the medical system. So we end up choosing what to show the world, deciding which parts of the chaos underneath get revealed. This plays out visually in my work, where there’s always this underlying chaos, but the surface only shows fragments of it, like an intentional filter of reality.

Artistically, Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-staining technique has been a huge influence. I love the freedom and unpredictability in how her paint moves across the raw canvas, and I use that same method to create these fluid, spontaneous shapes that feel alive and uncontrolled, much like how life with Lyme feels. Contemporary artist, Laura Owens, is also a major inspiration. I am interested in how she thinks about painting often asking herself “what a painting can be” which has helped push my paintings and practice. Another major influence on my work is an artist who also has Lyme disease, Jiatong Zoe Lu, and how they use their work for advocacy. Through their photography they convey their own struggles but also the Lyme community as a whole. This has made me think more of the similarities we have as a community through our experiences beyond the symptoms.

Fashion and pattern also play a big role in my work, especially in how I think about what we choose to present versus what remains unseen. I find myself looking to artists like Heather Day and Kathryn Macnoughton, who balance abstraction and design, letting layers interact in ways that feel intentional but also raw. I’m drawn to how they use color and form to create moments of tension and calm, something I try to bring into my own work as well.

I could go on forever, but lastly; the idea of concealment, whether it’s through fashion or digital platforms, really resonates with my work. I’m always thinking about the layer’s underneath – the chaos, the struggles, the things that aren’t so easy to see – and how we, both individually and collectively, decide to cover them up with something more polished or digestible for the outside world. It’s a constant push and pull between what’s real and what we let people perceive, and that’s something I explore through the layers and patterns in my paintings.”

Q: Your exhibition “A Single Tick” reflects your personal experience with Lyme disease. How did you decide to translate such a personal and painful journey into your art, and what was the most challenging part of this process?

Sims: ” Single Tick came from a place of wanting to turn something deeply painful and personal into something beautiful. Something that could educate and raise awareness, not just for myself but for others going through similar experiences with Lyme disease. Translating that journey into my art felt natural because art has always been a way for me to process what I’m feeling. But this series was especially important because I wanted it to serve as both a visual diary and a form of advocacy. I had to advocate for myself so much during my Lyme journey, and I wanted my art to do the same – advocating for others and educating the public so they could recognize the symptoms and avoid the same struggles with delayed diagnoses.

The most challenging part was the vulnerability. Lyme is something I deal with every day and exposing that in my work felt incredibly raw. I’m used to being careful about what I show and how much I reveal in relationship to my health because negative reactions. A lot of people suppress my complaints even the medical system. We are often told that “our labs our normal” or “everyone gets tired”. No one believes us so its hard to trust who to show it to. That’s why its so important to educate so people stop treating us this way. This series forced me to confront that, and honestly, I’m still grappling with it. It’s hard to put something so personal out there for the world to see, but at the same time, that’s what makes it powerful. Creating beauty out of such a negative part of my life was therapeutic in many ways, but it also meant I had to be real, open, and unguarded – and that’s not easy.”

Q: How do you cope with the physical challenges of creating art during flare-ups of Lyme disease symptoms, and has this limitation shaped your creative process in unexpected ways?

Sims: “My process has always been shaped by the need to manage my symptoms, so working slowly, resting a lot, and finding alternative ways to stay creative are just part of how I work. I’ve definitely gotten better at finding the balance between work and rest, though. Early on, I’d push myself too hard, and that would inevitably lead to flare-ups, setting me back even more. Now, I’ve learned to pace myself better. During flare-ups, I rely heavily on digital planning to keep ideas flowing, even if I’m stuck in bed. It allows me to stay connected to my work without overexerting myself. When I’m in the studio, I work more slowly and often while sitting down to manage my energy. While this process is slower, I’ve had to accept that it’s just how I work. I feel the pressure, especially as a grad student, to be in the studio constantly, but I know that my health has to come first. If I don’t take care of myself, I can’t create at all. So while it can be frustrating, I’ve found that this balance between work and rest is what allows me to keep going in the long term. My process may look different, but it’s what works for me, and I’ve come to embrace that.”

Q: Lyme disease awareness is one of the main goals of your art. What have been the reactions from your audience regarding the educational aspect of your work, and have you seen it inspire action or deeper conversations about the illness?

Sims: “The reactions I get are often something like, “Lyme disease? Is that when you get bit by a tick?” A lot of people don’t really understand what Lyme disease is, or how serious it can be. They don’t know about the long-term symptoms or the challenges that come with it. When I start sharing my personal story, people are usually amazed and surprised, and it often leads them to pull out their phones and start researching more about it. That’s always a really satisfying moment because part of what I’m trying to do with my work is raise awareness and spark that curiosity. Beyond just educating people about Lyme disease, my work has also inspired action. I regularly hold fundraisers and GoFundMe campaigns for Lyme organizations like Project Lyme, helping raise money for research, and I’ve seen a lot of people step up and contribute. It’s been rewarding to see people feel moved enough to not only learn more but to take real action.

Another amazing result has been how my work has opened up conversations about disability within art. It’s sparked deeper discussions about how health and illness shape creative processes, and how artwork influenced by disability is often overlooked in the art canon. These conversations are honestly my favorite part of sharing my work – they’re exactly what I was hoping to inspire. It’s about making people think differently about illness, art, and the intersection between the two.”

Q: What other concepts/ideas/thoughts do you want your greater body of work to convey?

Sims: “Apart from Lyme disease and resilience, a central theme in my work is the tension between control and chaos, perfect and imperfect. In my greater body of work and most recent work I am fascinated by the way we strive to present a “polished” version of ourselves, masking the mess and unpredictability underneath. This is something I live with daily, navigating both the mental and physical challenges of Lyme disease, but it’s also a universal experience. We all grapple with showing the parts of ourselves that feel “imperfect” while trying to project a sense of control.”

Q: Finally, you aim to inspire others to maintain a strong mindset in the face of adversity. What advice do you have for other artists dealing with chronic illness, both in terms of maintaining creativity and using art to advocate for causes they believe in?

Sims: “The advice I’d give to other artists dealing with chronic illness is: don’t compare yourself to anyone, especially able-bodied artists. Our practice is going to look different, and that’s okay. You’re not going to be in the studio all the time, and that doesn’t mean you’re any less of an artist. Resting and taking care of yourself is part of the process. Let yourself rest. If you’re not feeling well, don’t push yourself – you could make things worse. Do small things, like doodles or sketchbook drawings, or watch art talks on YouTube to keep the creativity flowing, even if you’re not physically making work.

It is also important to have a solid support system. For me, having a therapist has really helped with balancing the guilt of not always working and prioritizing my health. Family and friends who care and try to understand what you’re going through are essential, too. You’re making art for yourself, but you’re also showing it to convey something to an audience. That’s what being a professional artist is about – deciding what you want to communicate to the world.

For me, my work doesn’t scream Lyme Disease, so I use things like QR codes that take people to Lyme websites or create titles that get people thinking deeper. There are so many ways to advocate for what you believe in, and as an artist, that often becomes part of the job—whether it’s about identity, politics, or your own experiences. Art is such a powerful thing, and it gives you a platform to make people think and feel, so use it however feels right for you.”

You can learn more about Riley and her work by visiting her Instagram: artist_rileysims

*All images and information are © Riley Sims unless otherwise stated.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this interview are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Public Health Landscape or Valent BioSciences, LLC.