He was a prominent scientist, globally respected. When he spoke, people listened. “Every day the vaccination laws remain in force, parents are being punished, infants are being killed,” he wrote forcefully in a monograph. He accused doctors and politicians of pushing for mandatory vaccination based on personal interest without any certainty that the vaccines were safe. The World Health Organization said the epidemic was set to claim 400,000 lives per year already.

The law mandated vaccination for babies under three months. Tens of thousands of parents responded fiercely to what they saw as a dangerous violation of their children’s bodies. The simmering rage came to a boil in March when over 80,000 protesters nationwide came together to protest mandatory vaccination.

No, that’s not a scene from the COVID-19 pandemic. It was an 1885 protest in Leicester, England , and the eminent scientist was naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace. The epidemic was smallpox, for which a vaccine had just become available.

Ugochukwu, 2007

Almost 137 years later, on January 23, 2022, demonstrations erupted in cities worldwide to protest lockdowns and mandatory COVID-19 vaccination. In Canada, hundreds of 18-wheeler truckers led the so-called Freedom Convoy, in which between 8,000 and 18,000 citizens converged at the Prime Minister’s office to denounce mandatory vaccination as state regulation of their bodies and an outrageous abuse of their right to choose.

The same day, several thousand Americans braved the bitter cold of Washington D.C. to converge at the Lincoln Memorial and chant “No more mandates”, in a protest dubbed ‘Defeat the Mandates’.

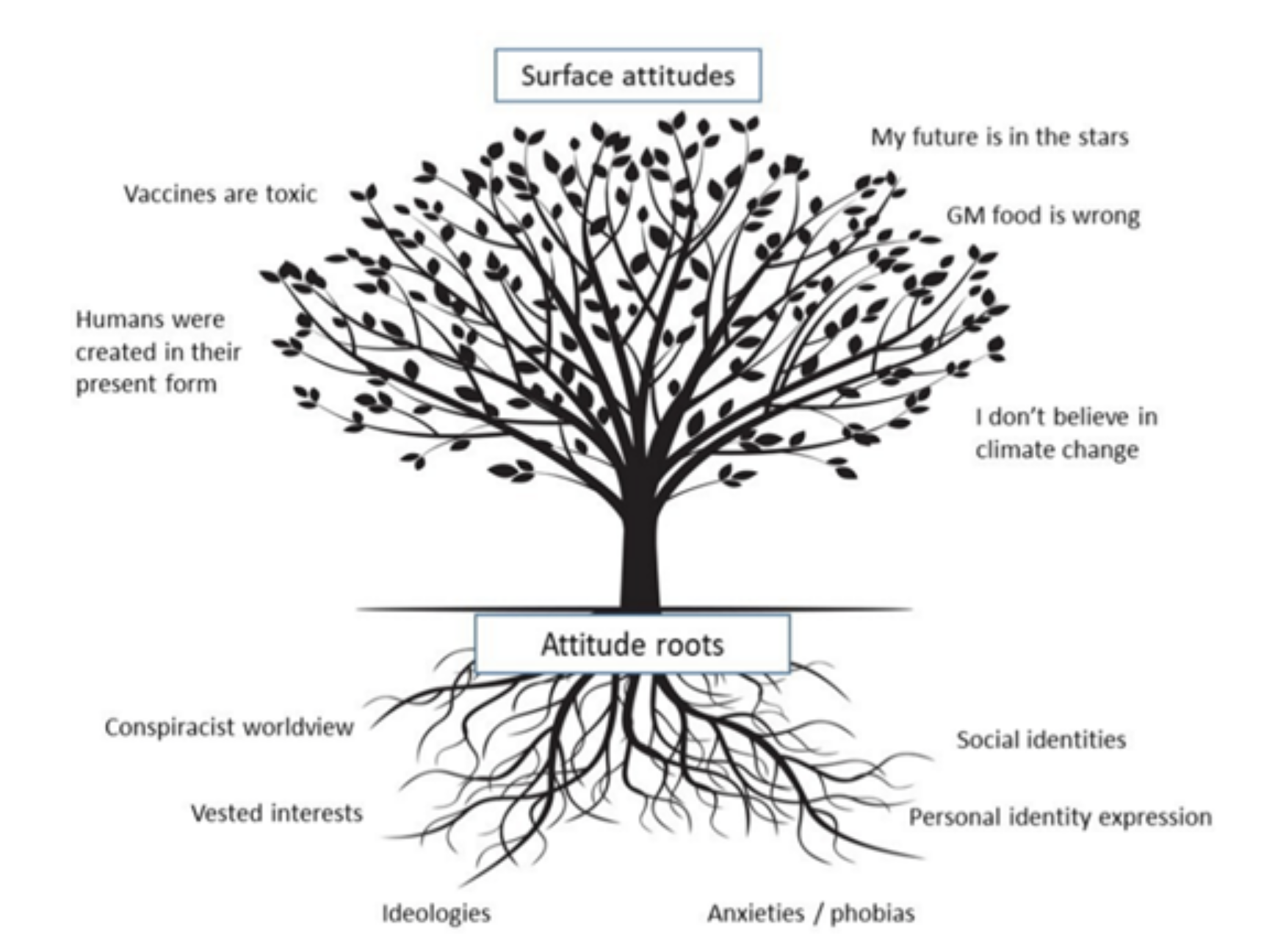

With vaccines, history repeats itself like music stuck in a loop. On the one hand, advancing technologies create vaccines against a growing list of lethal diseases and conditions. On the other hand, outrageous myths and conspiracy theories compete against science. Familiar and strong emotions run the gamut, from relief when deadly diseases like smallpox are eradicated to anger about perceived dangers to health, governmental overreach and threats to freedom of choice. While religious, commercial, pseudo-scientific and political interests cash in on the confusion, context and meaning are sometimes lost or forgotten. Telling facts apart from misinformation becomes difficult.

Understanding how vaccines are evolving can help better understand both why they are one of medical science’s supreme triumphs and also why the anti-vaccine movement continues to grow and influence so many.

Eight Steps to Today’s Vaccines

Mention vaccines, and names like Edward Jenner and Jonas Salk will come to mind. However, they were merely three of 10 scientists whose individual discoveries, spread out over 180 years between 1768 and 1954, led to traditional vaccine technology. They worked with imperfect knowledge: for example, till 1870, no one knew the role of germs in causing disease. Their methods would seem primitive compared with modern laboratory practices. Yet, with patience and rigor, each solved one part of the puzzle of how the immune system could be trained to recognize and protect the body against specific disease-causing bacteria and viruses.

(1) 1796: Edward Jenner demonstrates that vaccines are possible.

Edward Jenner noticed that milkmaids exposed to cowpox, a blistering disease of cows’ udders, came down with a mild case of blisters themselves but seemed immune to the dreaded smallpox, which claimed about 2 million lives every year. On May 14, 1796, Jenner injected pus from a milkmaid’s cowpox blisters into the arm of 8-year-old Mark Phipps . Six weeks later, when he injected Phipps with pus from a human smallpox victim, the boy did not develop smallpox.

Two years later, Jenner published a paper on his experiment, coining the term variolae vaccinae — literally “derived from smallpox of the cow” — and the word ‘vaccine’ was born. Jenner had demonstrated that vaccines work, though he could not have known how they worked. Within a year, physicians had inoculated thousands and proven Jenner’s method right. By 1979, thanks to the vaccine, smallpox was eradicated from the planet.

The smallpox vaccine had its share of serious mishaps. Transferring infected pus from one child to another was a method full of flaws and risks. About 3% of the people whom Jenner inoculated contracted severe smallpox and died, started a smallpox outbreak or caught a new disease like Tuberculosis because of the inoculation. Forty-one Italian children developed syphilis in 1861 after being given a vaccine contaminated with syphilis from an undiagnosed child. Vaccination caused a massive outbreak of hepatitis in Bremen, Germany, in 1883.

(2) 1885: Louis Pasteur shows that vaccines can be made from human pathogens.

On the morning of July 4, 1885, in Meissengott, in France’s Alsace province, a moody, rabid dog bit its master, Theodore Yone. A few hours later, in the marketplace, it savagely bit and wounded its second victim, a nine-year-old schoolboy, Joseph Meister, in 14 places. A bite from a rabid dog meant almost certain death back then.

But Mrs. Meister had heard that a Paris-based scientist called Louis Pasteur had been working on a cure for rabies for three years, and that’s where she took her son. Pasteur had perfected a method for immunizing dogs by injecting them with a version of the rabies virus too weak to cause the disease. History records that eventually, Pasteur saved Joseph Meister’s life, making him the first human being to become immunized through vaccination with a weakened version of a lethal virus.

Pasteur’s breakthrough came at a price. About 1 in every 200 vaccinated people became paralyzed and died from the vaccine itself. It took decades to identify the cause — the myelin basic protein that forms a sheath around nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord and to which some developed a fatal auto-immune reaction. The rabies vaccine, made from rabbit spinal cords, was rich in myelin basic protein.

(3) 1898: Martinus Beijerinck discovers the virus.

Martinus Boejerinck, a bacteriologist at The Netherlands Delft Polytechnic University, came to a startling conclusion during his experiments with tobacco mosaic, a disease that stunts the growth of tobacco plants. He squeezed diseased plants through a press and passed the sap through an unglazed porcelain filter capable of trapping bacteria. However, the resulting filtrate still caused the disease, leading him to conclude that a pathogen smaller than a bacteria must exist. Six years earlier, Russian botanist Dmitri Ivanovsky had come to a similar conclusion through his experiments. Beijerinck named the pathogen a virus and is regarded as one of the founders of virology.

(4) 1931: Alexis Carrel keeps animal organs alive outside the animal’s body.

In 1912, Alexis Carrel, a French-American working at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, cut a piece of heart out of an unhatched chick embryo and sustained it in a nutrient made of chicken plasma and a crude extract from a chicken embryo. He wanted to see how long he could keep the chicken heart cells alive. When he died in 1944, 32 years later, the chicken heart was still alive.

Till then, viruses for study and vaccine production had to be cultured within living hosts. Carrel’s innovation showed how animal organs could be kept alive outside the animal’s body and created new methods for growing viruses in quantity, enabling deeper research into viral behavior replication and pathogenicity.

His work, described in his paper On the Permanent Life of Tissues Outside of the Organism, won him the 1912 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in recognition of his contributions that modified and advanced tissue culture techniques.

(5) 1930s: Ernest Goodpasture shows that viruses can be grown inside eggs.

Ernest Goodpasture, a pathologist at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, was interested in fowlpox, a smallpox-like virus that infected chickens. Thinking that eggs would be sterile and cheap, he used an eggcup as an operating table, cut a small hole into the shell and injected fowlpox virus into it. To his delight, the virus multiplied happily in the membrane around the embryo.

In 1931, Goodpasture pushed virology to a new level with his novel method of culturing viruses. Before then, viruses could be grown for study only in living tissue or in vitro in a tissue culture. While the former was expensive and challenging to control, the latter was vulnerable to bacterial contamination.

Goodpasture’s method circumvented both these issues by using fertile eggs as the growth medium. After success with fowl pox, he cultured cowpox and cold sore viruses using this method. Two years later, he demonstrated that attenuated cowpox vaccine produced using his method would be purer and cheaper than the prevailing method of production in calf lymph. Later, this technique was used to create influenza and mumps vaccines.

(6) Mid 1930s: Max Theiler develops tissue culture to propagate viruses for vaccines.

South African emigré Max Theiler dreamed of creating a vaccine against yellow fever, the lethal hemorrhagic disease that caused death through jaundice and bleeding. Yellow fever research required laboratory monkeys at that time, but Theiler found that the virus could just as easily infect mice. This brought down costs and increased efficiency dramatically. Passing the viruses from mouse to mouse also clearly weakened their ability to infect human cells. (Today, we know that human viruses forced to reproduce in non-human cells undergo genetic changes that rob them of the ability to infect humans.)

Using Carrel’s method, he cultured the yellow fever virus through a succession of mouse embryos, reasoning that the better viruses became at reproducing in animal cells, the worse they would be when introduced to human cells.

When he injected eight Brazilians with this altered virus, they developed antibodies and stayed immune to yellow fever . Encouraged by the results, Dr Theiler conducted more human trials, leading to the vaccine’s launch and a nationwide vaccination campaign in 1938. By the decade’s end, millions of Brazilians were protected against yellow fever thanks to Theiler’s vaccine. His technique of culturing human viruses within animal organs, called tissue culture, became the gold standard for the next seven decades. In 1951, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his ground-breaking work with yellow fever.

Inevitably, great tragedy followed great success. In the early 1940s, a yellow fever vaccine that accidentally included serum from a person with undiagnosed hepatitis B infected more than 26,771 American service members, killing about 80 of them. That was the last time human serum was used in vaccine cultures.

(7) 1948: John Enders and others replace tissue culture with cell culture

At the Boston Children’s Hospital, Thomas Weller cultured fetal cells drawn from an aborted 12-week-old fetus and found that polioviruses grew well in them. Weller and his colleagues John Enders and Frederick Robbins demonstrated that polioviruses could be grown in various tissues from animal to human, creating a safer alternative to brain and spinal tissue, which fell out of favor after some people were found to have a fatal auto-immune response to the myelin basic protein. The three scientists shared the 1954 Nobel Prize for their work in creating this method.

(8) 1954: Jonas Salk creates the polio vaccine.

Jonas Salk, working at the University of Pittsburgh, was known as an obstinate, driven and strong-minded scientist, traits that proved useful in his mission to rid the planet of polio. Using the cell culture technique perfected by Enders and his colleagues, he propagated polioviruses in monkey kidney cells. He then killed them with formaldehyde, reasoning that dead viruses would not cause disease but would still trigger the body to create protective antibodies. Salk first tried the vaccine on himself and his family in 1953.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History

A year later, the polio vaccine was tested on 1.6 million children in the USA, Canada and Finland, the single largest vaccine trial to date. The results showed that Jonas Salk’s inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) was 80-90% effective in preventing paralytic poliomyelitis. The IPV was licensed the same day and became nationally available. In two years, annual polio cases dropped from 58,000 to 5,600. Five years later, only 161 cases remained.

Inevitably, Salk’s vaccine suffered its share of human error. Cutter Laboratories, one of the six pharmaceutical companies licensed to manufacture the vaccine, did a shoddy job, failing to ensure that all the virus particles had been killed. A few escaped and grew, leading to the worst human-made biological disaster in US history. Over 200,000 children were unintentionally injected with live, dangerous poliovirus and even spread it to others. In the final count, 40,000 of them developed mild polio, and 200 others, mostly children, were mildly paralyzed, while ten died.

Salk’s vaccine immunized people against polio but did not stop them from transmitting the virus to others. That loophole was finally closed by Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV). It worked brilliantly, was easy to administer and soon became the global norm.

In 1988, the World Health Assembly launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Vaccine production was expanded, and all countries participated. Only two cases of wild poliovirus, one each in Afghanistan and Pakistan, have been recorded globally as of July 2021.

A smorgasbord of technologies exists today for developing and manufacturing vaccines. A list would include –

- Live, attenuated vaccines containing viruses weakened or modified so they can no longer replicate or cause disease but can still trigger an immune response. Examples: Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR combined vaccine); Rotavirus; smallpox; chickenpox; yellow fever.

- Killed or inactivated virus vaccines, in which the pathogen is killed using heat or chemicals like formaldehyde or formalin. Harmless to humans but capable of provoking an immune response. Examples: Hepatitis A; influenza (shot only); polio (shot only); rabies.

- Toxoid vaccines for diseases caused by toxins released by bacterium responsible for diphtheria and tetanus. The vaccine contains an inactivated version of the toxin, capable of fostering the production of antibodies against future infections. Examples: diphtheria; tetanus.

- Subunit and Conjugate vaccines contain pieces of the pathogens they protect against. A subunit vaccine may present a specific protein from the pathogen, triggering the immune system to develop antibodies to that protein.

In Conjugate vaccines , a weak antigen, such as a piece of the bacteria’s coat, is combined with a strong antigen, such as a protein, as a carrier to sharpen the immune response. Examples: Hepatitis B; HPV (Human papillomavirus); Whooping cough (part of the DTaP combined vaccine); Pneumococcal disease; Meningococcal disease; Shingles. - mRNA or messenger RNA vaccines came into their own with COVID-19, taking manufacturing to a new level and breaking with the past. In mRNA vaccines, strands of RNA that encode for a specific spike protein are smuggled into cells within blobs of fat. Following mRNA’s instructions, the cells start churning out the spike protein, giving the immune system a target to prepare against. Example: COVID-19.

- Viral vector vaccines use a modified, harmless virus (for example, simian adenovirus) as a carrier for mRNA that encodes for a specific protein found on a virus’s surface, such as spike protein. Once the viral vector enters a human cell, it releases its mRNA passenger, which instructs the cell to manufacture more spike proteins for training the immune system. Example: COVID-19.

Sadly, however, for centuries each new vaccine has also given fodder to the anti-vaccine movement, providing ammunition to skeptics and dissenters even while bringing hope to millions.

Pierre Marshall

The dark roots of the anti-vaccine movement

Pus and scabs from a smallpox blister on a child’s arm are introduced into a cut on another child’s arm. She screams in pain. Her parents are confused, alarmed and angry. The anti-vaccine movement’s origins lie in moments like this and the laws that enabled them. Some clergymen believed that illness, wellness, life and death were all divinely ordained and that vaccination amounted to human interference in God’s plan. A 1772 sermon by the Reverend Edmund Massey argued that diseases were divine punishments from God. Preventing smallpox was a “diabolical operation”, he said, as good as blasphemy.

The first organized anti-vax movement, however, was a response to the Vaccination Act of 1853, which made vaccination mandatory for infants up to three months of age, with punishing fines for parents who refused. The Anti-Vaccination League and the Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League sprang up, as well as numerous anti-vaccination journals. Leicester, in particular, was a hotbed of anti-vax activities, and the demonstration march of 1885 stands even today as one of the world’s largest anti-vax protests, including banners, a child’s coffin and an effigy of Jenner. It was only in 1898 that the penalties were removed from the Vaccination Act, and a “conscientious objector” clause was added.

The anti-vaccine movement spread to the United States in 1879, shortly after smallpox broke out there, through William Tebb, an English businessman and social reformer who had been fined 13 times for his refusal to vaccinate his third daughter. The New England Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League and the Anti-Vaccination League of New York City were formed. Throughout the nation, as fast as laws empowering the government to mandate vaccination were enacted, court cases were filed to swat them down.

Several new vaccines were developed over the decades from 1920, starting with the toxoid vaccine against diphtheria. The pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine debuted in 1914, followed by vaccines for polio in 1955, measles in 1963, mumps in 1967 and rubella in 1969. The anti-vaccine movement woke from its slumber, spurred by the new vaccines. Misinformation began to flow again.

One infamous name stands out in the narrative of the modern anti-vaccine movement: Andrew Wakefield. A British gastroenterologist, Wakefield, published a paper in The Lancet in 1998 falsely claiming to have found a plethora of intestinal symptoms related to autism, a condition he named autistic enterocolitis. It went unnoticed that the study involved only 12 carefully selected children and no control group. The paper wondered in passing if the symptoms might be linked to the measles vaccine, but at a press conference later, Wakefield doubled down on this, asserting without evidence that he had found a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The triple vaccine, he said, was unsafe.

Vaccine opponents swung into action, energized by Wakefield’s false assertion. By 2002, 10% of science stories in the UK were about the MMR vaccine. Abetted by sensational media that indiscriminately disseminated Wakefield’s claims, vaccination rates plummeted. Virulent outbreaks of measles once again became common.

Wakefield’s hoax was finally exposed thanks to a persistent journalist named Brian Deer, who revealed in 2004 that Wakefield had been paid £55,000 by solicitors seeking evidence against vaccine manufacturers. He had received £435,643 more from lawyers who expected him to prove that MMR did not work. As for autistic enterocolitis, Wakefield had conjured up the disease, hoping to sell a remedy for it later.

The Lancet, conceding that it had been duped, retracted Wakefield’s paper. Wakefield, disgraced and publicly shamed, was stripped of his medical license. But by then, the seeds of irrational fear and skepticism he had sown had taken deep root. Wakefield had single-handedly converted what had been a movement into a crusade.

In 2019, WHO listed vaccine hesitancy among the world’s top ten threats to public health .

Anti-vax grows up with COVID-19

In 2004 and 2006, Facebook and Twitter appeared, changing the face of the global anti-vaccine movement by passing control of vaccine misinformation and disinformation into the hands of individuals, many of them with large, loyal online followings. Traditional media, reviled as purveyors of “fake news”, were replaced by online influencers, experts and ‘citizen’ journalists. The movement also took a political turn, alleging, for example, that a few evil global elites were working with governments and greedy Big Pharma to achieve diabolical ends through vaccines, including depopulating the world; injecting nano-chips along with vaccine shots to track and manipulate citizens; and making people guinea pigs for untested vaccines with undocumented deadly side-effects.

However, an unusual study in May 2024 challenged the assumption that vaccine hesitancy and skepticism were caused by online misinformation. The study reasoned that to be harmful, misinformation must be widely seen and impact vaccine-related behavior. Using Facebook’s large-scale Social Science One dataset, the study measured the views of 13,206 URLs about the COVID-19 vaccine published during the first three months of 2021 and shared publicly over 100 times each on Facebook.

Their results were surprising. URLs flagged by Facebook’s fact-checkers as false, out of context and so on received only 8.7 million views, or a mere 0.3% of the 2.7 billion vaccine-related URL views.

More pernicious and widespread than flagged misinformation, the study found, was exposure to true-but-misleading vaccine-skeptical content that cast a shadow of doubt on COVID-19 vaccines. For instance, the most viewed URL in the study, a Chicago Tribune story headlined A Healthy Doctor Died Two Weeks After Getting a COVID Vaccine; CDC is Investigating Why, was seen by 54.9 million Facebook users. URLs related to this story were seen at least 68.7 million times – more than six times the views of all flagged misinformation combined.

How successfully has the anti-vaccine movement dissuaded people from vaccines? The 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor , the most extensive report to date, based on a survey of 140,000 people from about 140 countries, found that —

- 92% of people in the world think it is important to vaccinate children.

- Only 7% of people worldwide disagree that vaccines are safe, and 5% disagree that they are effective. On safety, France topped the list, with 33% disagreeing; on effectiveness, Liberia leads the skeptics, with 28%

- In many countries, more than 50% “neither agree nor disagree” that vaccines are safe or effective. They may be more vulnerable to vaccine disinformation and misinformation.

- Support for vaccines is highest across South Asia at 98%; 97% in South America; 94% in Northern Africa; and 92% in Southern Africa. Support is still high but lower across North America (87%); Western Europe (83%); and Eastern Europe (80%).

Meanwhile, vaccine technology has progressed steadily. Nearly every time, it has been the pressure of an epidemic or pandemic that has opened the doors to new frontiers.

How epidemics spurred vaccine technology

What do smallpox, rabies, influenza, Ebola and Covid-19 have in common, apart from being deadly and dreaded diseases that have erupted in epidemic or pandemic form over the last 200 years? They all led to significant advances in vaccine technology. The history of vaccines is a record of human ingenuity against extreme disease threats, reaching back to times before disease itself was hardly understood.

Smallpox: The practice of variolation, in which a person was intentionally exposed to minute quantities of dried scabs or pus taken from smallpox sores to fortify them against the disease, was known to exist as far back as the 1400s. Some sources even date it back to 200 BCE. However, it was Edward Jenner in 1796 who took the first small step towards modern vaccine technology by showing that a cowpox infection could fortify a person against a smallpox infection. Like other scientists of his time, Jenner achieved his breakthrough without knowing why it worked. No one then knew about germs or the immune system.

Rabies: Pasteur thought Jenner’s method should also be capable of producing vaccines against other diseases. His attention was on chicken cholera, a lethal disease wiping out breeding chicken populations. By 1878, he had cultured the disease-causing bacteria in his laboratory and was inoculating chickens. One day, a negligent assistant injected chickens with an old bacterial culture that had lost its potency. Pasteur noticed that the birds showed only mild signs of the disease and that they did not become ill when injected with fresh bacteria.

It was a game-changing moment for immunology when Pasteur realized that a weakened pathogen could strengthen the body’s ability to fight off full-strength disease, sometimes even after infection. The rabies vaccine he created later exploited this principle.

Influenza: No single disease has perhaps been as influential as influenza in pushing the boundaries of vaccine technology. Thirty-four influenza epidemics, including nine pandemics, were recorded between 1404 to the middle of the 19th century. One of the most devastating was the pandemic of “Spanish” influenza in 1918–1919, which infected about 500 million people and killed an estimated 21 million worldwide.

Of the three identified flu viruses, A, B and C, the most elusive and lethal is influenza A, capable of antigenic shift, which happens when two strains of the virus — say, one from a human and one from a bird — co-infect the same cell. Here, they mingle, exchanging gene segments to create a novel influenza virus with significantly different surface antigens that can escape detection by the immune system, leading to epidemics and pandemics.

For example, the Asian flu pandemic of 1957-58 that claimed between 1.5 and 2 million lives was caused by the H2N2 flu virus. The Hong Kong flu pandemic of 1968, which resulted in over a million deaths, was caused by the H3N2 flu variant. The so-called bird flu epidemic of 2003-2008, which mainly affected birds and humans who had direct contact with them, was caused by the H5N1 variant.

Under enormous pressure to develop a vaccine, scientists and researchers backed by the US Army developed the world’s first flu vaccine, using inactivated flu virus, in the 1940s. It was authorized for general use in 1945.

Keeping pace with this shape-shifting virus made vaccine technology adept at identifying new variants. Releasing seasonal flu vaccines twice a year is now standard public health practice. Other vaccine technologies born of influenza research include bivalent, trivalent and quadrivalent vaccines, offering protection against multiple strains of the virus; subunit vaccines, which use fragments of the virus; and recombinant DNA vaccines.

Ebola: Till 2014, when Ebola broke out in West Africa, there had been neither concern nor funding for Ebola research and vaccine development. Big Pharma had no interest in a disease that emerged sporadically, and that too in impoverished countries. In the 30 years since it was discovered in 1976, Ebola has killed about 1,300 people. The world was not alarmed.

However, groups of dedicated, underfunded scientists across the USA, Canada and Europe had been quietly setting the stage for the Ebola vaccine. The groundbreaking moment came in the early 1990s when John Rose, a Yale University scientist, figured out how to use a livestock virus called VSV — the vesicular stomatitis virus — to deliver vaccines to human beings. VSV can infect people but not sicken them because the body swiftly produces surprising levels of antibodies

In 1994, Rose attached a protein from an influenza virus to VSV, creating a vaccine that worked like magic in mice. Creating an Ebola vaccine required replacing VSV’s surface protein — a glycoprotein — with an Ebola glycoprotein. That finally happened when Canada built its National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg with biosafety level 4 facilities.

By the time WHO reported a “rapidly evolving” Ebola outbreak in southeastern Guinea on March 23, 2014, the Canadian laboratory had already developed a human-grade Ebola vaccine, named rVSV-ZEBOV, ready to be tested in an epidemic setting. By that weekend, Ebola had reached Guinea’s capital, Conakry, marking the disease’s debut in an urban setting. By March-end, there were suspected outbreaks in neighboring Liberia. There was a real possibility that this time, Ebola would go global.

The wheels of enterprise began to turn on August 8, when WHO announced a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). Unprecedented global collaboration ensued between governments, the pharma industry, NGOs, donors and communities. The Ebola R&D initiatives launched that year bore fruit in 2021, delivering two vaccines, two biological treatments and one reliable rapid diagnostic test against the Zaire strain of Ebola.

COVID-19: Arguably humankind’s first disease that touched nearly every country on the planet, COVID-19, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-Cov-2, was declared a pandemic by WHO on March 11, 2020. At the time of this writing, 775,917,102 individuals have been infected, and about 7 million of them have died, according to reported figures.

COVID-19 evoked a diverse and concerted pandemic response, becoming the staging ground for unprecedented global collaborations between governments, donors, the pharma industry, NGOs and communities, all working together at never-before speeds. For example, Moderna Therapeutics’ vaccine was ready for human trials on March 17, just six days after WHO officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Many countries, including Cuba, Iran, Brazil, Russia, India and China, produced their own COVID-19 vaccines using traditional methods. To date, over 20 different primary vaccines have been created globally, using vaccine technologies such as viral vector, protein subunit, inactivated virus, mRNA and DNA. Each vaccine type has issued dozens of booster formulations in response to variants like Delta, Omicron and KP.2. A complete list might include as many as 240 COVID-19 vaccines and boosters. Official reports from national public health agencies indicate that 13.58 billion doses of COVID‑19 vaccines were administered worldwide as of May 2024.

Unlike any other pandemic, COVID-19 also provoked a global public backlash of skepticism, anger and protests like never before. While the anti-vaccine movement fed off this and fanned the flames, there was genuine anguish as it became clear that COVID-19 had unanticipated long-term effects that unpredictably affected different organs. Many suspected that in its hurry to create and sell vaccines, Big Pharma might have taken shortcuts that affected safety, quality and efficacy. With the pandemic receding, disturbing details are emerging.

For example, mRNA’s action against SARS-COV2 qualifies it as a gene therapy product (GTP) , subject to more rigorous regulation and pre-approval testing than vaccines. Inexplicably, though, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicine Agency (EMA) excluded mRNA vaccines from GTP regulation without providing scientific or ethical justification. The long-term safety monitoring of GTPs requires several years, whereas vaccine regulations only call for a few weeks.

As a result, essential tests that would have been carried out for GTPs were omitted for mRNA vaccines. Unexplored areas included the risks of damaging DNA; the vaccine’s genetic material becoming embedded in a person’s DNA and being passed on to future generations; the presence of cancer-causing mutations; unintended harm to developing embryos or fetuses, and toxic effects at birth. Other worries include the long-term effects of the vaccine staying active in the body; harmful effects from repeated doses, and the possibility of the vaccine being released into the environment through body fluids such as semen.

While COVID-19 vaccines saved millions of lives, there is mounting skepticism and anger at the list of non-COVID fatalities and lethal side effects that seem linked to the vaccines. There are growing concerns about shortcuts and missteps in pushing through mRNA COVID-19 vaccines too quickly without much understanding of their long-term effects.

Meanwhile, mRNA technology has been evolving undeterred at breakneck speed, far outpacing the capacity of regulatory systems to update and standardize testing and approval protocols. Offering a plug-and-play solution to disease prevention and treatment, mRNA has been a game changer in vaccinology, enabling rapid, scalable, safe and cell-free manufacture of prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines.

The result has been a stunning range of stunning futuristic approaches, technologies and experimental vaccines, some already in phase 3 clinical trials.

The shape of vaccines to come

Could a vaccine target something other than a pathogen? Scientists are finding that mRNA vaccines can be aimed at any cells deemed harmful or undesirable, such as those involved in cancer, Alzheimer’s or aging, as long as they carry one or more distinctive external antigens, typically proteins, glycoproteins, polysaccharides or peptides.

This insight is at the heart of today’s emerging technologies, such as mRNA vaccines, nanoparticle (NP) vaccines, viral-like particle (VLP) vaccines and universal vaccines. An NP vaccine consists of nano-sized particles made from lipids, proteins, polymers or metals. Engineered to mimic the structure of a pathogen to provoke an immune response without causing disease, these nanoparticles carry antigens —proteins, peptides or other molecules that can trigger the immune system.

In VLP vaccines, a subset of NP vaccines, the nanoparticle consists of lab-made virus-like molecules that mimic the virus. VLPs cannot replicate in cells but can trigger an immune response.

Personalized anti-cancer vaccines

Evolving mRNA technology offers the never-before possibility of personalized cancer vaccines. Like pathogens, cancer cells display tumor-specific antigens (TSAs), also known as neoantigens. Caused by mutations, these proteins can vary from patient to patient. Personalized mRNA cancer vaccines could be a landmark in oncology, opening the door to precise, finely honed treatments to train the immune system to target a specific patient’s specific tumor cells, eliminating the cancer and fending off a relapse.

Recently, Moderna presented results from its phase 2 trial of a personalized mRNA vaccine to fight melanoma, a lethal skin cancer, in 157 patients with stage 3 or stage 4 melanoma who had undergone tumorectomy.

For nine months, each person in the test group, comprising two-thirds of the participants, received a monthly dose of a cancer vaccine tailor-made to target 34 neoantigens unique to their cancer. In addition, they were given Merck’s immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab every three weeks for a year. The remaining one-third received only pembrolizumab.

Overall, 75% of the patients taking the two therapies survived with no recurrences at 2.5 years, compared to 56% of those on only pembrolizumab. The ongoing phase 3 trial includes 1,000 participants.

Moderna and Merck are also testing the approach with squamous cell carcinoma, both before and after surgery, as well as in kidney and bladder cancer patients. Meanwhile, phase 2 clinical trials for autogene cevumeran, an experimental personalized vaccine against pancreatic cancer created by BioNTech in collaboration with Genentech, began in July 2023. To make the personalized vaccine, scientists sequence the tumor after it is surgically removed to identify 20 protein mutations with the highest potential to produce the best neoantigens. The mRNA ferries instructions for creating these proteins into the cell, presenting the immune system with targets.

The phase 1 results demonstrated how the vaccine’s ability to stimulate a durable immune response for as long as three years could reduce the risk of the dreaded disease returning after surgery.

Future-proof universal vaccines

Thanks to its high transmissibility and global spread, SARS-CoV-2 was prolific in generating variants, including Alpha, Beta, Delta and Omicron, along with their numerous subvariants. The shapeshifting seasonal flu virus had already made nimble vaccine development a public health need. With COVID-19, research began to turn towards ‘future-proof’ universal vaccines that could provide a broad range of protection against existing and future coronaviruses, including their variants.

DIOSynVax (Digitally Immune Optimised Synthetic Vaccines), a spinoff company of the University of Cambridge, approached this by using computer simulations to identify the virus’s Achilles heel, namely critical regions that are unlikely to mutate, such as the sections the virus needs to complete its life cycle.

Using this approach, researchers identified a unique antigen structure that generated broad-based immune responses against a large group of naturally-occurring SARS and SARS-CoV-2-related viruses that occur in nature. Human clinical trials at Southampton and Cambridge NIHR Clinical Research Facilities will end by September.

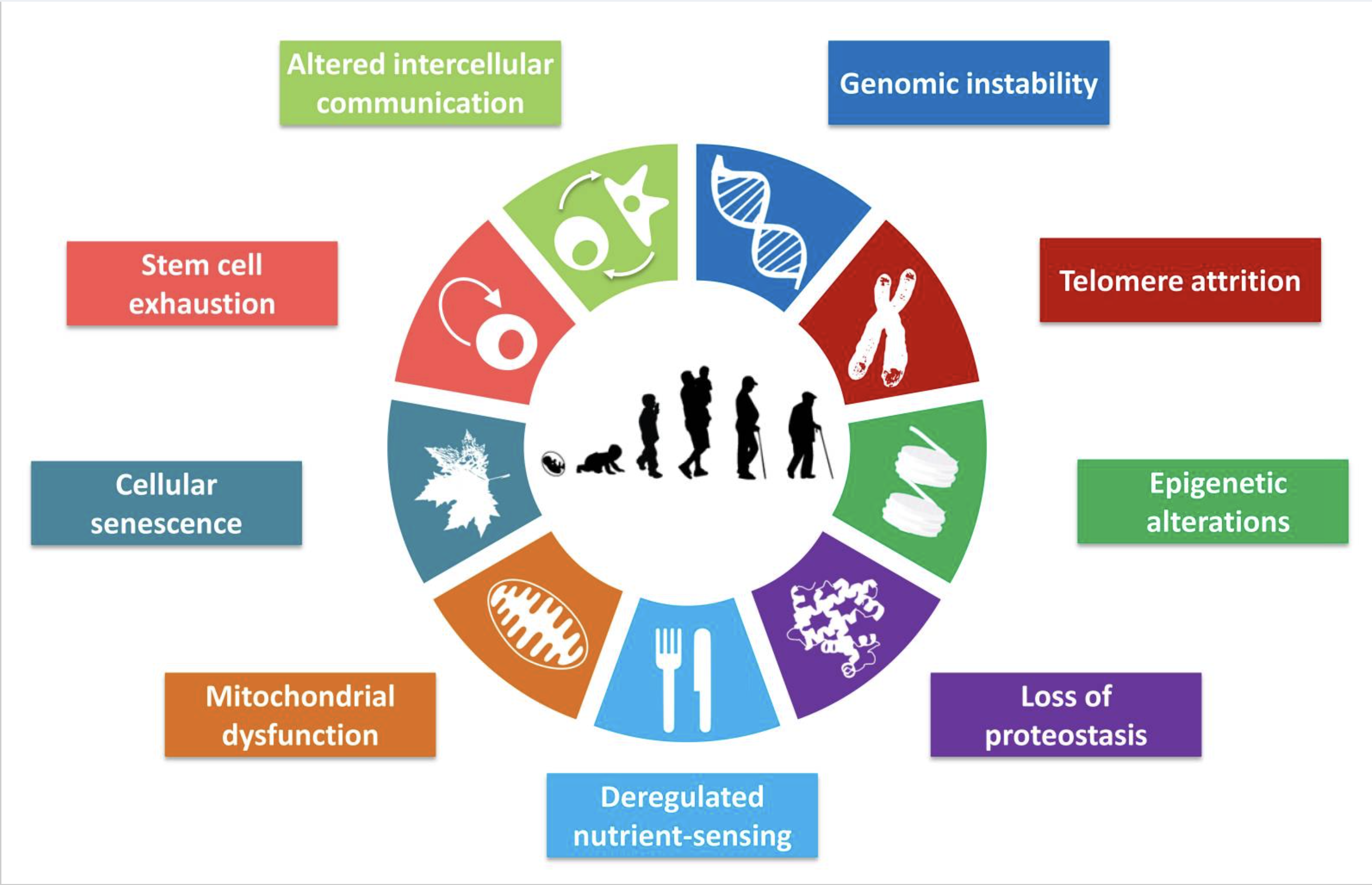

A vaccine against aging

When the body ages, so do its cells, accumulating DNA damage through environmental stress. Eventually, they stop replicating and become senescent cells. The body flags them as obsolete, and the immune system clears them out before they turn cancerous. But immune cells become senescent too; the hunter becomes the hunted. The accumulation of these inactive, senescent cells is a key part of aging and contributes to many of its symptoms and diseases.

Many senescent cells express a protein called GPNMB. Could a vaccine be developed to target cells displaying this protein? Researchers in Japan successfully tested a peptide-based vaccine that targeted senescent cells with GPNMB in young mice on a high-fat diet, middle-aged mice, and mice with progeria, an accelerated aging disease. The treated mice had fewer molecular markers of aging and also fewer metabolic abnormalities.

“There may be many more seno-antigens produced by other kinds of senescent cells,” said Professor Tohru Minamino, an author of the study. He speculates that one day human patients may receive personalized anti-senescence therapy based on the profiles of their senescent cells.

Goodbye to Alzheimer’s?

“I have, so to speak, lost myself.” These words were spoken in 1901 by Auguste Deter, the first person to be diagnosed with this neurodegenerative disease, later named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer, Deter’s psychiatrist. Since then, the heart-wrenching and tragic disease has remained a dreaded condition of old age, all the worse because doctors barely understood its causes and pathology, and could offer nothing therapeutic, palliative or prophylactic against it. WHO recently projected that the global cost of dementia, of which 60-80% is accounted for Alzheimer’s, could reach $2.8 trillion by 2030.

Dr. Alzheimer, dissecting Auguste Deter’s brain post-mortem, identified plaques between the neurons — sticky beta-amyloid protein deposits containing tangles of an unknown protein called tau. Could vaccines target these proteins and arrest or reverse the patient’s cognitive decline?

At least seven Alzheimer’s vaccines designed to trigger the immune system to target the beta-amyloid or tau proteins related to the disease are now in clinical trials. The front-runner is Vaxxinity’s UB-311, designed for people with mild Alzheimer’s. UB-311, which triggers antibodies against beta-amyloid plaques, generated a robust immune response and slowed cognitive decline by about 50% in its phase 2 clinical trial in Taiwan. If it fares well in its phase 3 trials, it is scheduled for release in 2030.

The difficult truth about vaccines is that even the most cutting-edge technologies will not make a difference if people fear or mistrust vaccines. One of the most moving appeals to such people comes from beloved children’s author Roald Dahl. His eldest daughter Olivia caught measles in 1962, before a reliable measles vaccine existed. Olivia’s measles developed into a deadly condition called measles encephalitis, and she died within 24 hours.

During the late 1980s, when anti-measles-vaccine sentiment had brought the disease surging back with over 80,000 cases a year in the UK, Roald Dahl wrote a powerful open letter aimed at their parents, with a single message: It is almost a crime to allow your child to go unimmunized. The letter, powered by his storytelling skills and his grief at the loss of his darling daughter, was widely distributed and read.

At least 20 of the 100,000 children who develop measles every year in the UK would die, he wrote in the letter. He continued —

LET THAT SINK IN. Every year, around 20 children will die in Britain from measles. So what about the risks that your children will run from being immunized? They are almost non-existent. Listen to this. In a district of around 300,000 people, there will be only one child every 250 years who will develop serious side effects from measles immunization! That is about a million-to-one chance. It is almost a crime to allow your child to go unimmunized.

The author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory could not resist adding:

I should think there would be more chance of your child choking to death on a chocolate bar than of becoming seriously ill from. . . immunization.