Humanity’s growing demand for animal meat is driving a planetary crisis, accelerating climate change, devastating ecosystems, and threatening public health.

Two grim, almost surreal, 26-story buildings tower over the southern outskirts of Enzhou, about 500 miles west of Shanghai in China’s Hubei province. No one would mistake them for apartment complexes despite their neat grid of window-like slots. Indeed, their main inhabitants are not human at all. The buildings are designed specifically to meet the biological and reproductive needs of 600,000 pigs each. Here they will be bred, farrowed, fattened, and finally slaughtered to meet the exploding animal protein needs of China, which consumes half the world’s pork and is also its biggest pork producer.

It is the world’s largest vertical pig farm, designed to manufacture 54,000 tonnes of pork every year. The building’s design reflects its unique function. Each of its six giant elevators can hoist a load of 10 tons, or about 100 pigs, at a time. Every utility and process, from the building’s water supply, electricity, and air conditioning, to its automatic feeding machines and smart air filtration and disinfection systems, can be monitored and controlled centrally from a NASA-like command center on the first floor. A stupendous amount of pig manure is processed daily in a biogas-driven waste treatment system and turned into electricity for lighting and heating the buildings. About 400 such ‘pig-rises’ could meet a part of China’s and the world’s growing appetite for animal proteins.

China is a classic example of an unsettling global trend with dire ramifications for human health, public health, animal welfare, and climate change: skyrocketing demand for animal proteins as a result of economic growth and increasing incomes, particularly in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Since 1985, the Chinese family’s income has grown by an average of about 7.6% every year. Over the same period, the Chinese adult’s appetite for animal meat has gone through the roof, from about 10 kg per year in the 1970s to 70 kg today. Although Chinese health authorities suggest 40 to 75 gm of meat daily, in 2024, the average Chinese consumed 250 gm. Half of that was pork, an animal so prized in Chinese culture that since the 1970s, the government has maintained a strategic pork reserve of about 200,000 tonnes deep-frozen at 0°F over a dozen facilities, for use in crises and price spikes. China’s demand for pork alone is expected to grow from 51.77 million tonnes (Mt) in 2023 to 60.77 Mt in a decade.

A world of carnivores

China is a striking instance of the global surge in the human appetite for animal meat as incomes increase and living standards rise. Although people in wealthier countries tend to eat more meat per person, developing economies in Africa, and South and Southeast Asia are fast catching up. By 2050, the planet will carry 9.6 billion people, most of them from burgeoning economies in developing countries, and about 70% of them urban. They will want more meat on their tables and in greater variety. Together, they will account for a titanic increase in the global demand for animal protein.

What would 2050 look like? A 2012 working paper from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) predicted nearly a doubling of global demand for meat. A more recent study by the Scientific Foresight Unit of the European Parliamentary Research Service predicts growth of 57% for meat and 48% for dairy. However, such estimates can easily shift upwards or downwards by the accelerating influence of climate change and the rapid emergence of alternative proteins. They also ignore the complex ways that industrial production of animal proteins affects our health and damages the environment and biodiversity.

Poultry will probably be the planet’s most sought-after meat by 2050, with demand expected to be around 180 million tonnes (Mt), well more than double the 82 Mt it was in 2005. Global fish consumption might increase nearly 80% by 2050 compared to 2010, with the total weight of the world’s fish harvest potentially nearly doubling from 80 Mt in 2015 to almost 155 Mt. The figures can be misleading; in weight, seafood would outstrip poultry, requiring harvests between 250 and 300 Mt. Mutton and lamb, popular meats in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, would almost double in demand, though the quantity needed would only be around 25 Mt. Demand for pork, the most consumed meat in China and many Southeast Asian diets, would increase by about 30% to reach about 143 Mt. Beef consumption would grow moderately in wealthy countries, where demand has peaked and is no longer responsive to rising income or lower prices. However, because of rising demand in emerging economies, global demand for beef would still be about 50% more in 2050 than in 2010, standing at about 105 Mt.

According to FAO, to meet this demand, the world would have to produce roughly 200 million additional tonnes of meat annually by 2050, bringing total global meat output to around 470 Mt per year. About 72% of that meat will be consumed in LMICs in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

A good question to ask would be: How did we get here?

The Meat-eater’s Dilemma

Humans have been eating meat for millennia, long before anyone knew about proteins, which only entered the conversation a few centuries ago. Cut marks on animal bones from the Olduvai Gorge and other East African sites indicate that early humans scavenged meat using stone tools, and probably ate meat in combination with plant foods. The discovery of fire some 400,000 years ago profoundly altered human diet and nutrition, not only by destroying pathogens and making food safer, but also by reducing chewing time and accelerating brain growth.

About 12,000 years ago, meat consumption diversified with the development of agriculture and the domestication of sheep, goats, pigs, cattle, and poultry. It became a part of banquets and rituals in civilizations as diverse as Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, and the Indus Valley. Pastoralists like the Mongols and Scythians, and the Inuit, relied heavily on meat and animal fat for sustenance and survival.

Meat was a luxury and a badge of wealth as recently as 500-1500 CE, when game, beef, pork, and poultry were reserved for the consumption of the elite. Peasants had to make do with cereals and legumes. The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, along with the development of transportation, refrigeration, and preservation methods, changed everything, making meat global.

Chicago slaughterhouses pioneered assembly-line butchery, spurring massive growth in consumption in the West, parts of Asia, and Latin America. By the end of the 20th century, with populations soaring, economies thriving, and living standards on the rise, the demand for meat mushroomed into a global nightmare. In response, meat production moved from the farm to the factory, with feedlots, battery cages, antibiotics, mechanized assembly processing, and a corporate focus on speed, quantity, growth, and profits.

The Age of Protein

In the 1700s, chemists like the French Antoine Fourcroy identified several proteins, such as gluten, fibrin, gelatin, and albumin, and clubbed them together as ‘albumins’. In 1838, the Dutch chemist Gerardus Johannes Mulder discovered that all proteins were made of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen, leading to the first scientific description of proteins. The name, derived from the Greek word for primary, was suggested by his associate, Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius.

By the early 1900s, scientists knew that proteins were polypeptides, that is, made up of chains of amino acids. Over 500 amino acids exist in nature, but the most important ones, from a human point of view, are the 22 that are used in proteins and appear in the genetic code of life. The first of these amino acids was isolated from asparagus in 1806 and named asparagine. By 1935, scientists had identified all 20 amino acids that the human body needs to grow, develop, and function. Of these, the body was able to synthesize 11; the remaining nine, alas, had to be outsourced. Meat, which happens to contain all these nine amino acids, is called a complete protein. However, vegans can equally get the missing nine through combinations of vegetables, legumes, pulses, and grains.

The emphasis on eating protein became a standard in nutrition policy and recommendations around the early 19th century. For this, we may thank Justus von Liebig, a versatile German scientist and one of the founders of biochemistry, who declared proteins to be a ‘master nutrient’ and central to the physiological growth of animals and humans. Using his wide-ranging knowledge of plant nutrition and plant and animal metabolism, he developed a theory of nutrition, arguing that not only meat fiber but also its juices, rich in inorganic chemicals, should be consumed. As a way of retaining these liquids, he recommended searing meat rather than boiling or roasting it, or else cooking it as a stew or soup.

Watching the Industrial Revolution unfold, he realized that protein production too could be mechanized, which was a radical thought that sowed the seeds of profound transformation in the meat and dairy industries. In 1865, he set up Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company, which even today markets beef extract in cubes under the Oxo brand.

Liebig’s emphasis on protein from meat and animal products has endured for two centuries and is now a cornerstone of the food industry and many cuisines and diets. In the 1890s, it even influenced the United States Department of Agriculture to set an extraordinarily high daily protein recommendation of 110 gm per day for working men. The modern Dietary Reference Intakes published by the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) are more modest: only 0.8 gm of protein per kilogram of body weight, which translates to about 56 gm per day for men and 46 gm per day for women, which is the equivalent of two eggs, a half-cup of nuts, and three ounces of meat. Americans consume almost twice that amount, according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Kristi Wempen, dietitian in Nutrition Counseling and Education in Mankato, Minnesota, says, “Contrary to all the hype that everyone needs more protein, most people in the US meet or exceed their needs.”

We have entered an age of worldwide obsession with protein intake and an explosion of demand for animal proteins. The global protein supplements market size was $28.15 billion in 2024. The market is projected to grow from $30.40 billion in 2025 to $55.32 billion by 2032 at a combined annual growth rate of 8.93%. North America dominated in 2024, with a market share of 37.09%, and is projected to reach USD 22.58 billion by 2032, driven by the fitness boom and muscle-building trends .

Environmental and Climate Consequences

The industrialized production of meat takes a hammer to the planet’s environment, accelerating climate change and magnifying its harm. Food production systems already contribute about one-third of total global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, almost two-thirds of which come from animal-sourced foods. If we reach 2050 without finding alternative protein sources, we will see a 21% increase in per capita meat consumption and a 63% increase in total consumption and GHG emissions.

Producing one (1) kg of beef, one of the most climate-intensive foods on our menus, requires 1,451 liters of water, the equivalent of 10 bathtubs, and creates about 99 kg of greenhouse gases (GHGs), or the equivalent of a drive from Los Angeles to San Diego in a petrol car. The main GHGs are methane released by cows and emissions from growing animal feed.

Another common favorite, cheese, also comes with a steep environmental price tag. Making one (1) kg of hard cheese requires about 10 liters of milk and uses up about 5,600 liters of water (37 bathtubs). This gives it a carbon footprint of around 23 kilograms of CO₂ equivalents per kilogram of cheese, or roughly the same as driving a petrol car from Boston to Providence. And this is without factoring in the carbon cost of the refrigeration that cheese requires.

Fouling the Air, Killing Forests

Humans’ insatiable appetite for meat is straining every earthly resource – the land, the seas, the air, the forests, the ecosystems, and the biodiversity – to breaking point. Livestock farming is responsible for 12-14% of global GHG emissions, a figure that comes perilously close to the combined emissions from the global transport sector, 15-16%. Livestock farming accounts for 37% of global emissions of methane and 65% of global nitrous oxide. Both gases pose significantly larger threats to our atmosphere than carbon dioxide, which is emitted throughout the supply chain, particularly when forests are cleared to grow crops for animal feed. Factory-farmed beef requires twice as much fossil fuel energy input as pasture-reared beef.

More disturbing, factory farming is notoriously profligate in its use of land, needed for grazing cattle and growing crops like soybeans for animal feed. In the United States, about 260 million acres of forests, which are nature’s carbon sinks and vital ecosystems, have been laid bare for growing crops like soy, corn, and grains, over 67% of which will directly feed animals rather than humans.

Globally, the crisis is acute. In South America, pristine rainforests have been cleared to grow soybeans and grains as feed for beef cattle. Animal agriculture is directly responsible for over 75% of the deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest. One estimate predicts that by 2050, nearly 40% of the Amazon will have disappeared as agriculture expands. In the Congo Basin, pristine rainforests the size of Bangladesh were slashed and burned between 2000 and 2014 to grow crops for animal feed. Farm animals consume a third of the planet’s grain production and occupy a third of the planet’s ice-free land.

Factory farming guzzles another endangered planetary resource, freshwater, accounting for 55% of the U.S.A.’s water consumption and 16% of the planet’s. In stark contrast, humans use barely 5% of the planet’s freshwater.

However, the most dire aspect of industrial meat production is its potential to unleash a Pandora’s box of new infectious diseases on humans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warns that “3 out of every 4 new or emerging infectious diseases (EID) in people come from animals”. Any of them could be the next pandemic. We are entering an era of self-inflicted wounds caused by our appetite for meat.

A Blitz of New Diseases

Cramming tens of thousands of animals into the confines of a factory farm creates a paradise for pathogens to rapidly multiply and evolve by creating a “crowding effect” where an infection can spread explosively. In a pasture-based environment, where animals are more dispersed, pathogens would be destroyed by UV radiation in sunlight before they infect other animals.

Factory farms have been called ‘evolution vessels’ or amplification chambers for pathogens. A virus that can infect birds or bats may not be dangerous to humans at first. However, in the densely crowded confines of a hog or poultry farm, it can easily mutate and evolve millions of times as it jumps from animal to animal, sickening entire populations of birds or pigs. The chances of an accidental mutation that can infect human beings rise astronomically. Such a disease spillover from an animal species to human beings, whether caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi, or parasites, is called a zoonosis. Every zoonotic disease has the potential to become a pandemic.

A study by the Humane Society International on the connection between animal agriculture, viral zoonoses, and global pandemics identified five ways that human interactions with animals, especially in factory farms, could trigger the next pandemic.

- Spillover of pathogens from one species to another, especially when factory farms push into forests and other wild areas, forcing viruses present in wildlife into contact with farm animals. Once a virus adapts to spread among domesticated animals, it has a much easier pathway to reach humans, opening the door to a pandemic.

- Viral amplification, when deadly, new strains of a pathogen can evolve thanks to tens of thousands of stressed animals densely crammed together in closed sheds, their immune systems battered and weakened. A single new strain can spread like wildfire, just one mutation away from a spillover and a pandemic.

- Farm concentration, where many large farms are located close together, accelerates viral spread from one farm to another through workers, equipment, vehicles, and even cross-currents of air. A small outbreak can morph into an epidemic, increasing the chances of a spillover to humans.

- The global live animal trade, where millions of animals are shipped every year across countries and continents, makes the problem international. It takes only a few infected animals for a pathogen to spread worldwide, far beyond its place of origin.

- Live animal markets, fairs, and auctions act as mixing bowls for disease. Animals from different farms and regions, each with its own microbes, are exhibited in close quarters before the public. In these crowded hubs, a pathogen such as the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 can spill over from animals to humans and then rapidly migrate globally through cities, planes, and trade routes, sparking a pandemic.

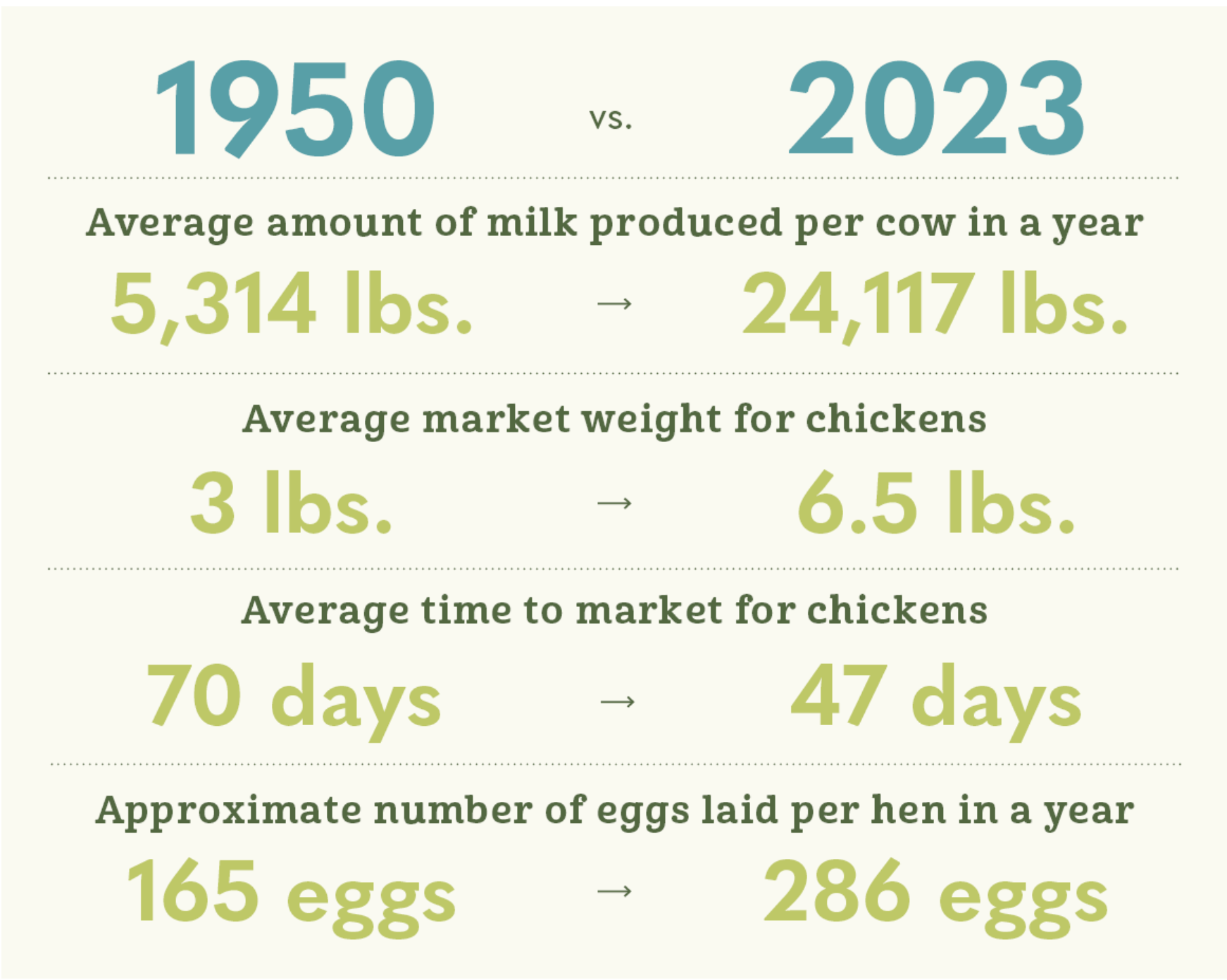

Focused on mass production, profit, and standardized output, Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) have applied the logic of the assembly line to living systems, in the process creating a profound vulnerability to disease that no amount of biosecurity can fully mitigate. Chasing after single-trait excellence, they have taken dangerous shortcuts like cross-breeding to accentuate traits like rapid growth or high milk yield. In the process, valuable natural traits have been lost, such as the ability to survive extreme temperatures, limited water supplies, poor-quality feed, rough terrain, or high altitudes. The few, highly tailored commercial breeds created by such methods have almost no biological diversity. Virtually identical genetically, they are now perfect targets for single pathogens, which can sweep through a facility with catastrophic efficiency.

When the Microbes Resist

A vicious cycle now begins. To ward off infections, factory farms overuse and misuse antibiotics extensively, not for treating sick animals but as prophylaxis and growth promoters. This in turn spurs the evolution of pathogens immune to those drugs, creating deadly superbugs that are unaffected by any existing human medication, a phenomenon now known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR). According to the CDC, factory farms account for 70% of America’s antibiotic use. Global antimicrobial use on factory farms is projected to increase 67% by 2030, and that too in regions with weaker regulations.

Antibiotic-resistant infections are becoming increasingly difficult and expensive to treat, and more often fatal. These infections kill an estimated 35,000 Americans every year and an equal number in the European Union and the European Economic Area. A 2023 World Animal Protection study linked one million human deaths globally to factory farm antibiotic abuse, with projections indicating this figure could double to two (2) million annually by 2050 if current trends continue. The World Health Organization (WHO) has included AMR among the planet’s top 10 health threats, and estimates that bacterial AMR directly caused 1.27 million global deaths in 2019 and contributed to 4.95 million. The World Bank predicts that by 2050, AMR could cause US$1 trillion in additional healthcare costs.

Something Fishy About Fishing

Many think of fish as a viable, less pernicious protein source than terrestrial animal meats, with a low and acceptable carbon footprint and environmental impact. Fish is an indispensable and key source of protein and micronutrients for over three billion people. Nearly 10% of the world’s population relies, at least partially, on fisheries for their livelihoods.

Globally, fisheries and aquaculture production, including algae, aquatic animals, and aquatic products, surged to 223.2 Mt in 2022, a 4.4% increase over 2020. Aquaculture surpassed capture fisheries as the main producer of aquatic animals for the first time in history, with 130.9 Mt, of which 94.4 Mt were aquatic animals, over half of the total aquatic animal production.

Yet, the truth is chilling: the industrial farming of fish is every bit as lethal and destructive to the planet as terrestrial farming for beef, chicken, and pork. Because it occurs mainly in the distant waters of open oceans, and much data is self-reported, it draws less attention than other animal meats. The main problem is overexploitation, when fish are removed from the ocean faster than their populations replenish themselves. According to FAO, in 2019, only 64.6% of the world’s marine fishery stocks were being fished within biologically sustainable levels, down from 90% in 1974. Stocks fished at unsustainable levels had zoomed from 10% to 35.5% of assessed stocks by 2025.

The methods used to capture and farm fish are doing irreparable harm to the oceans, the air, the biodiversity of the planet’s marine life, and the future of fish on this planet. For example, in the cold waters of Norway’s fjords, the prized Atlantic salmon is disappearing. The cause, ironically, is aquaculture, often touted as the solution to depleting stocks. Unlike factory farms, which stand on land, salmon farms exist in the ocean waters within Norway’s sheltered fjords and bays, using open-net cages suspended in the water. A cage is like a small, circular stadium, 130-200 ft in diameter and 65-100 ft deep, equivalent to over 10 Olympic-size swimming pools.

A single net can stock 50,000 to 200,000 fish, and that is where the problems begin. They range from salmon urine and feces, in volumes comparable to the daily sewage output of a town of 60,000 people, to genetic contamination when hundreds of thousands of farmed salmon escape and interact with wild salmon, diluting or erasing specific traits like predator awareness, stress tolerance, and fitness.

The steady rain of uneaten fish food and salmon waste sinks to the seabed, where it smothers a range of vital benthic (deep-sea dwelling) creatures ranging from microscopic bacteria and worms to starfish, sea cucumbers, crabs, clams, mussels, corals, sponges, snails, and sea urchins. The waste is rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, the same ingredients found in fertilizers, and although essential to marine life, in large quantities they create a nutrient overload, known as eutrophication, which can trigger toxic algae blooms that eventually create low-oxygen ‘dead zones’.

Alv Arne Lyse, Project Manager, Wild Salmon, at the Norwegian Association of Hunters and Anglers, says, “It’s immoral that a single industry can destroy nature like this.”

The Violence of Farmed Salmon

One of aquaculture’s paradoxes is that feeding carnivorous farmed fish like salmon requires harvesting small, open-ocean ‘forage fish’ like anchovies, sardines, and mackerel. It can take as much as three to four lbs of such fish to produce just one (1) lb of farmed fish. Forage fish consume phytoplankton, which produce nearly half the Earth’s oxygen. They are also energy sources for larger predators, including seabirds, marine mammals, and commercially important fish. Forage fish are the ‘middlefish’ that help transfer energy from phytoplankton to larger fish species higher up the food chain.

When salmon farms deplete forage fish, the aftershocks are felt throughout the ecosystem. Predators like tuna, cod, seabirds, seals, and whales lose a major food source and face starvation and a decline in their numbers. Lower down, there is an explosion of zooplankton that the forage fish used to eat. This can lead to a fall in phytoplankton, the microscopic creatures that form the base of the marine food chain, releasing oxygen and fixing carbon.

A staggering number of diverse fish are destroyed daily as bycatch, which refers to unwanted fish and bird species that are netted unintentionally along with the target fish. One estimate puts bycatch at over 40% of all fish harvested annually, approximately 38 million metric tonnes. Over 650,000 marine mammals, many of them protected and vulnerable, die as bycatch worldwide every year. Annual estimates include 720,000 seabirds, 300,000 whales and dolphins, 345,000 seals and sea lions, and over 250,000 turtles.

Perhaps the most brutal of fishing practices is bottom trawling, in which a heavy, weighted net is dragged along the sea bottom, sweeping up deep-dwelling marine life while indiscriminately destroying everything in its path, including fragile habitats like corals and seamounts. Off the Tasmanian coast, bottom trawling reduced the bottom cover of stony coral (Solenosmilia variabilis) a hundredfold and brought down by 66% the richness, diversity, and density of starfish, sea urchins, sponges, corals, crabs, and lobsters. They have not recovered even a decade later.

Dietary Choices and Environmental Impact

What we choose to eat has always been guided by what we’re told is “good for us.” But the field of public health nutrition has always been fickle, with guidelines changing or even being reversed as new research changed concerns and priorities. Experts continually try to piece together how different nutrients, foods, and eating patterns affect health, and then translate their conclusions into nutrient reference values (NRVs), recommendations, and guidelines that can be used to shape policies and regulations. The outcome has been a baffling succession of shifting perspectives and recommendations on what should be on the table. We live in an age of diets, each claiming to be exactly what our bodies need.

Among the most eulogized is the Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, olive oil, fish, and moderate wine, reflecting traditional eating patterns of Southern Europe.

Another popular one, the Atkins diet, focuses on a low-carbohydrate plan that progressively reintroduces carbs after an initial strict restriction to promote weight loss.

The Paleo diet is modeled on foods presumed available to early humans, such as meat, fish, nuts, fruits, and vegetables, while excluding grains, legumes, and dairy.

The Ketogenic diet is a low-carbohydrate, high-fat regimen designed to induce ketosis, where the body burns fat instead of glucose for energy.

The Vegetarian and the Vegan diet share many qualities, but the latter is more rigorous, excluding all animal-derived products, including dairy, eggs, milk, and sometimes even honey.

Contrary to all the hype that everyone needs more protein, most people in the US meet or exceed their needs.

Kristi Wempen, dietitian in Nutrition Counseling and Education

The Fickle World of Dietary Science

It’s difficult to imagine a time when no one thought about diets and health, but in the early days of nutrition science, known as the Foundation Phase, science understood neither food nor health very well, and disease was attributed to “poisonous vapors”, known as miasma. A more systematic, science-based approach emerged with the advances in chemistry in France, biochemistry in Germany, and germ theory. Food safety and processes like pasteurization were emphasized, based on the understanding that invisible microorganisms were the enemies.

Phase 2, called the Nutrient Deficiency Era, started around 1910 and focused on micronutrient deficiencies, driven by emerging knowledge about “vital amines’ (vitamins) which then remained the mainstay of nutrition research for the next three decades. By the 1950s, all the major vitamins (A, B complex, C, D, E, and K) had been isolated and synthesized.

The first ever set of NRVs, published by the League of Nations in 1937 and followed by the USA and Canada, included just nine nutrients: protein, calcium, iron, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, ascorbic acid, and vitamins A and D. With growing scientific understanding, that list has grown to over 30 macronutrients, vitamins, minerals and trace elements.

The phase of Dietary Excess and Imbalances started from about 1940, as chronic non-communicable diseases like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) began to rise. Data from the Framingham Study and the Seven Countries Study suggested that saturated fat and cholesterol in the diet were the culprits behind CVD, and led to one of the most persistent and aggressive recommendations in the history of nutrition guidelines: replacing saturated fats from animal sources with vegetable oils as a way to lower blood cholesterol levels and prevent heart disease. This phase was marked by decades of obsessive monitoring of lipids and cholesterol, and the emergence of statins for cholesterol management. Eventually, meta-studies debunked the dietary fat hypothesis, pointing instead to chronic inflammation from lifestyle and stress, in addition to diet, as the underlying factors.

Since about the 1970s, we have been in the troubled waters of phase 4, when diets must not only meet human health requirements but also planetary health needs and species survival. In this Food System Sustainability era, increasing recognition of environmental challenges, coupled with dismal success in curbing obesity and chronic diseases, has led to a New Nutrition Science aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. These dietary guidelines recognize that a diet cannot be called healthy or sustainable for humans if it damages the environment.

A 2023 study compared the sustainability of Mediterranean, Paleo, Ketogenic, Vegetarian, and Vegan diets, defining diet sustainability using three metrics defined by FAO: environmental impact, nutritional quality, and affordability. Not surprisingly, Vegan, Mediterranean, and vegetarian diets emerged as the most sustainable across all metrics, while meat-heavy diets, such as the ketogenic diet, had the greatest negative environmental impact. Diets with higher nutritional quality included the vegan, paleo, and Mediterranean diets. Diets rich in meat and animal products performed poorly overall, but especially in terms of environmental sustainability. The inescapable conclusion was that people interested in nutritious but sustainable food should go with plant-forward diets.

A New Menu for Tomorrow

One of the most radical approaches towards a sustainable diet started innocuously in 2010, when a 31-year-old Norwegian pathologist called Gunhild Anker met and married her Prince Charming, a Norwegian billionaire called Petter Stordalen. With his support and resources, she realized that she could think big, and shifted from medicine to global health. In 2013, she set up a foundation called EAT to bring science, politics, business, and civil society around one of the most difficult questions facing humanity: how can we feed the planet without destroying it? EAT wanted to start dialogues between people you would normally not find together around a table, such as farmers, chefs, scientists, CEOs, and UN officials.

A year later, tragedy struck. At just 35, Grunhild was diagnosed with systemic sclerosis, a rare, life-threatening autoimmune disease that hardens the skin and internal organs. The treatments were brutal, including a stem cell transplant in the Netherlands, and Grunhild faced a real possibility that her project would die stillborn. But instead of stepping back, she dug in and redoubled her efforts.

In 2019, EAT teamed up with The Lancet, one of the world’s oldest and most influential medical journals, to launch the EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, Health. She became the public face of the “planetary health diet,” appearing at Davos, the UN, TED, and pretty much any intersection of food, climate, and health. It was difficult to ignore her; Grunhild was intelligent, glamorous, and relentlessly optimistic, even when critics called her ideas too elitist or utopian.

The Commission gathered 37 scientists from 16 countries, representing fields as diverse as nutrition, ecology, agriculture, political science, and public health. After years of debate and number-crunching, the Commission unveiled its report proposing a planetary health diet: Our Food in the Anthropocene: Healthy Diets From Sustainable Food Systems. A flexible template rather than a rigid meal plan, it recommended lots more fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes; moderate amounts of fish and poultry; very little red meat and sugar. The diet was framed not just as a way to prevent heart disease, diabetes, and obesity, but also to feed nearly 10 billion people by 2050 without wrecking the planet’s ecosystems.

The EAT-Lancet report landed like a bombshell. Some praised it as visionary, others called it too idealistic, culturally insensitive, or unaffordable in poorer countries. Despite the debate, it was the first time that policymakers and the public had a clear North Star for sustainable food. Since then, the Commission’s ideas have been used in climate talks, national dietary guidelines, and countless debates about how we should farm and eat in an ever-crowded, warming world.

Looks Like Meat, Tastes Like Meat

Meanwhile, plant-based innovations have begun pushing the boundaries of culinary science, making it literally possible to taste and experience meat without eating real meat. The evolving technologies come with esoteric names such as spinner, shell cell, and freeze casting. The undisputed market standard is extrusion, which excels at burgers, mince, sausages, and nuggets, and has been adopted by companies such as Beyond Meat, Impossible Foods, Nestlé, and Unilever. Extrusion produces plant-based meats with a recognizable bite and chew similar to ground meat or chicken chunks. It is remarkably close in taste because of its excellent capacity to bind to fats and flavors. Impossible Burgers synthesizes soy leghemoglobin from the roots of soy plants to recreate the red, bloody color of its burgers. When cooked, it turns brown, just like real beef, and releases meaty, umami flavors.

Freeze casting is effective in creating meats that look and tear in flakes like the muscles of chicken and fish. Some think of shell cell technology, in which proteins and fats are reconstructed in layers, to be the promising new kid on the block, still in its early days. It has the potential to recreate the marbling and bite of steak, as well as a complex chew.

The most otherworldly of these technologies is surely 3D printing, which offers meticulous, layer-by-layer control over the composition, texture, look, structure, and even taste of plant-based proteins, creating meat analogues that can be customized to individual specifications such as protein origin, flavors, and even looks. With its laser-like precision and capacity to craft intricate geometries, 3D printing is highly efficient, with negligible waste and a small ecological footprint.

However, plant-based meats have still not matched real meat in terms of their protein payload. Skinless chicken breast (100 gm) delivers 31 gm of protein. The same weight of lean ground beef and pork loin carries about 26 gm of protein, while salmon or tuna would average 22 gm. No plant-based meat comes close to these, except for vEEF steak (31 gm) and Get Plant’d steak (25 gm). Also, plant-based meat analogues have 5–45 g carbs/100 g, mainly from binders like starches, grains, and pea proteins. Real meat has none.

While scientists inch towards solutions, however, nature is not waiting. Traditional communities in places like Africa are already seeing their protein sources dwindle and disappear as the climate changes. One tribe in Kenya has responded swiftly by transforming its diet and switching to a new, unexpected protein source.

There were 77 camels, and they had been walking across the stark, surreal landscapes of northern Kenya for seven days, crossing dried-up lake beds, vast salt-crusted plains, shifting dunes, and black volcanic rocks. Their destination was a dusty village in the semi-arid brushlands of Samburu County, about 249 miles north of Nairobi and home to the Samburu tribe. The governor, Jonathan Lati Lelelit, had arrived in his SUV to distribute the camels to lucky herders.

Hundreds of villagers had walked miles to attend the camel lottery, full of hope that they would take home a camel. Many remembered the Samburu adage: The cow is the first animal to die in a drought; the camel is the last. Each camel costs $600; so far, 4,000 have been brought in to replace the cows of Samburu.

“If there were no climate change, we would not even have bothered to buy these camels,” said Lelelit. “We have so many other things to do with the little money we have. But we have no option.” The three-year spell of brutal droughts that started in 2000 was the worst in the recorded history of the Horn of Africa. About 80% of the Samburus’ cows, their chief protein source, perished. Malnutrition and illness ravaged the modest population of 310,00 pastoralists, especially their youngest and the oldest. One report speaks of the smell of rotting cattle carcasses all over Samburu.

Forty-two-year-old Leleina, with two wives, 10 kids, and 150 cows, was once wealthy by Samburu standards. But after the droughts, his cows disappeared rapidly, a few dozen stolen by raiders and more than a hundred starving to death. When the rains resumed, he had only seven cows left. He himself lost weight and fainted easily and often from weakness.

Like many others, Leleina went for the camel lottery. It was his lucky day: his number was called and he became the proud owner of camel #17.

Though the world has so far viewed it as an unprepossessing and marginal species of limited use, there is growing awareness that the camel just might be an animal whose time has come in a world being wracked by extreme climate. With the thin legs of a greyhound and the tightly muscled mid-section of a horse, they can survive two weeks or more without water; a cow would not last more than a day or two. They can lose 30% of their body weight in water without consequences; a human being would die after 12%. They regulate their core body temperature in ingenious ways to align with the desert’s cycles of extreme heat and cold. Their meat is comparable in protein and other values to beef, though it is somewhat chewier. And a camel produces six times as much milk as a cow even through the severest of droughts. With even one camel, Leleina’s family had better chances of having milk during the next drought.

“Then there is a ripple effect,” he said. “The camel gives birth. The population grows. Camels are survivors.”

The clock is running out for humans to discover if they, like the camel, are also survivors.