In the last couple of decades, the lush rainforest around the remote village of Meliandou in the heart of Guinea has become patchier. Animals, like bats, saw their habitats dwindle and in a quest for survival, they sought refuge in closer proximity to human environments, making the boundaries between species thinner. A hollowed-out tree in the middle of the village became home to a colony of bats.

About 50 meters from the same tree, in the heart of Meliandou, a two-year-old boy named Emile lived with his family. In a matter of days, Emile fell ill with an unknown virus, developed a high fever, and died. Soon the same virus, that scientists now believe Emile got from the bats, took the lives of his sister, mother, and grandmother. The village, surrounded by a ring of forest, unexpectedly became the epicenter of a devastating outbreak that would leave an indelible mark.

Between 2014 and 2016, an Ebola outbreak claimed the lives of more than 11,000 individuals throughout West Africa, making it a threat to global public health. Over the years a vast number of scientists found a correlation between spreading viruses like Ebola, which passes from animals to humans, and deforestation.

When two-year-old Emile caught Ebola, the region had already experienced extensive deforestation due to activities like mining, logging, and farmland expansion, mostly by local communities looking to support their families. The animals that usually carry the Ebola virus lost their habitat and started to live closer to humans, potentially leading to a higher likelihood of viral transmission.

Ebola is just one of the zoonotic diseases that turned into a massive outbreak and scientists say the risk is way higher. According to the IPBES report “an estimated 1.7 million currently undiscovered viruses are thought to exist in mammal and avian hosts. Of these, 631,000 to 827,000 could have the ability to infect humans.”

Causes and extent of deforestation

Deforestation, the process of clearing or removing large areas of forests or wooded land, has long been a global issue. The rate of deforestation has slowed down over the last three decades, but it still remains a major concern due to its adverse effects on the environment, wildlife, and climate change. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that since 1990 about 420 million hectares, more than the size of India, of forest have been lost and converted to other land uses.

More than 96% of deforestation happens in the tropics. In the year 2022, the world saw a loss of 4.1 million hectares of tropical primary forests, illustrating a rate of deforestation equivalent to vanishing 11 soccer fields’ worth of forest every minute.

Deforestation is a result of a mix of natural events and human actions. While things like forest fires, hurricanes, and droughts can cause damage to forests naturally, it’s mostly what humans do that’s the big driver of deforestation.

One of the leading factors behind deforestation, accounting for nearly 90%, is agricultural expansion. On a global scale, the conversion of forests into croplands accounts for more than 50% of the total forest loss. According to the FAO’s findings in the 2021 Global Remote Sensing Survey utilizing satellite data, approximately 40% of forest loss is linked to livestock grazing.

As the world population increases, there is a growing demand for food, leading to the expansion of farmland and the clearing of forests to create space for crops or grazing areas for livestock. This includes both commercial and subsistence (small-scale) agriculture. Large-scale commercial agriculture, especially for animal feed and biofuels has emerged as a significant driving force behind the most substantial decline in natural habitat in the Amazon region over recent decades.

The products of large-scale agriculture and industrial production are often widely traded commodities, used in various industries around the world. In Fact, every six seconds, a forest area equivalent to the size of a football pitch is cleared to create space for producing these commodities – mainly soybeans, palm oil, rubber, and timber.

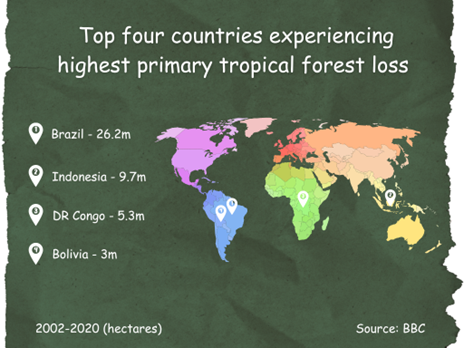

On top of agriculture, projects like building roads, highways, dams, and mining sites often mean cutting down forests, causing deforestation. Mining (sometimes illegal), especially for minerals, oil, and gas, also requires removing forests and can seriously harm the environment nearby. The top four countries most affected by deforestation are Brazil, Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Bolivia. BBC reported in 2021 that deforestation has reached the highest level since 2006. A study the same year revealed that approximately 94% of deforestation and habitat destruction that happened until 2020 in Brazil’s Amazon and Cerrado regions might be unauthorized or illegal. This equates to a total of 18 million hectares of habitat loss, which is larger in size than the combined land areas of Denmark, Holland, Belgium, and Switzerland, according to WWF.

The Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, has seen a deforestation level of around 17%, with its tipping point projected to be between 20-25%. Should the tipping point be exceeded, the vast rainforest could potentially transform into a dry grassland, at best, according to Amazon Conservation.

The vital role forests play

Forests play a crucial role in supporting biodiversity, regulating climate by absorbing carbon dioxide, and providing essential resources for human well-being – including clean air, water, and timber.

Well-managed and protected forests act as “carbon sinks,” meaning they absorb more CO2 than they release. However, when forests are degraded or destroyed, they can become “carbon sources,” emitting more CO2 than they capture.

Forests are the source of food and fuel for over 1.6 billion individuals. While around 70 million people globally, including many Indigenous groups, call forests their home.

These forests are also climate change allies. As carbon sinks, they store it, moderating temperatures and mitigating climate effects. With rising sea levels and fiercer weather, forests aid flood control by absorbing water and preventing rapid runoff. Their roots curb erosion, safeguarding communities from landslides and mudslides.

Deforestation disrupts the water cycle, causing soil erosion, reduced water retention, runoff, and water pollution from harmful substances entering water bodies. Clearing forests also removes natural air filters (trees), causing higher air pollution from greenhouse gas and particulate emissions. Calculations suggest that safeguarding Amazon’s indigenous territories could prevent more than 15 million cases of respiratory and cardiovascular ailments annually, resulting in savings of approximately $2 billion USD in healthcare expenses.

Forests also play a crucial role in Earth’s balance, serving as intricate ecosystems that offer refuge, sustenance, and breeding grounds for countless organisms. From tiny insects to massive mammals, a diverse array of life finds a home in these natural habitats. It means that deforestation doesn’t just destroy trees, the entire ecosystems could be gone.

And that in return sets the stage for something else.

Healthy forests prevent the spread of diseases by acting as natural barriers. Certain animals within these forests, like predators and scavengers, control the population of disease-carrying organisms, such as rodents, reducing the risk of transmission. The complex ecosystem of a healthy forest supports biodiversity, making it harder for any one disease to dominate and spread.

Once these forests are removed the contact between humans and wildlife increases dramatically, potentially leading to disease transmissions. Some researchers found that the impact of deforestation might not solely be determined by the extent of forest loss; the manner in which deforestation occurs could be equally crucial. As a forest becomes fragmented, an increasing number of edges form along clearings’ borders. These edges could provide opportunities for virus-carrying animals to interact with humans.

“The key implication is that forest clearing has a direct impact on human health,” Andrew J. MacDonald and Erin A. Mordecai wrote in their report.

Diseases, such as vector-borne (diseases transmitted to humans or animals from vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks) and zoonotic diseases can be affected by deforestation. Zoonotic diseases are diseases that can be transmitted between animals and humans, such as COVID-19 and Ebola. Around 60% of newly emerging infectious diseases stem from zoonotic sources, and out of this, about 70% come from wildlife.

The correlation between the spread of the Ebola virus and deforestation has been studied by many scientists. One of them is Julia E. Fa, Professor of Biodiversity and Human Development at Manchester Metropolitan University. She and her colleagues employed remote sensing methods to explore how deforestation, both in terms of timing and geographical extent, correlated with Ebola outbreaks in Central and West Africa. The findings indicate that the higher chance of a potential outbreak in a location is connected to recent instances of deforestation and, thus, preserving the forests could potentially lower the risk of future outbreaks.

“If you open up an area of forests, more bats come in, more people are in there, so it may be that you have a combination of both things to increase the probability of viruses jumping from animals to humans,” she explained.

In the early 1990s, a yellow fever outbreak started in Kenya’s Kerio Valley as the forest there became fragmented due to deforestation. When forests are cleared, numerous species vanish, but certain ones manage to adjust. Among those who adapted were howler monkeys, which can harbor yellow fever. They became more densely concentrated, thereby potentially raising the risk of infections spreading at a faster pace.

… an estimated 1.7 million currently undiscovered viruses are thought to exist in mammal and avian hosts. Of these, 631,000 to 827,000 could have the ability to infect humans.

IPBES Workshop on Biodiversity and Pandemics

A 2021 study by Serge Morand and Claire Lajaunie showed that from 1990 to 2016, there was a notable rise in the occurrences of both zoonotic and vector-borne diseases, which appear to be associated with deforestation worldwide. Researchers identified connections between epidemics and deforestation primarily occur in nations located in the intertropical zone with substantial forest coverage. These include countries like Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia in South America, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Cameroon in Africa, as well as Indonesia, Myanmar, and Malaysia in Southeast Asia, among other regions.

While there is a vast amount of research available, Fa says we still have a lot to learn about dynamics in biodiversity and the spread of viruses. She thinks the “indisputable proof of association” still has to surface.

“We don’t know what’s happening, but we know there is something happening because we have a correlation between outbreaks and deforestation.”

Vector-borne diseases and mental health impact

Vector-borne diseases like Zika and malaria not only cause physical suffering but can also deeply affect mental health. The unpredictable and debilitating nature of these diseases can lead to increased anxiety, fear, and stress among those affected. The lengthy recovery process, ongoing symptoms, and potential long-term effects can contribute to feelings of helplessness and depression.

In a recent nationwide study in Denmark conducted by researchers from Columbia University Irving Medical Center in the U.S. and the Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health, it was discovered that patients who had received a hospital diagnosis of Lyme disease – now the fastest growing vector-borne disease in the U.S. – experienced a 28% higher prevalence of mental disorders. These individuals were found to be more likely to have attempted suicide after the infection, in comparison to those without a Lyme diagnosis, and had an increased risk of actual suicide.

Lyme disease is by far not the only vector-borne disease with a mental health impact. A much earlier study in 2007 found that 31% of patients with West Nile virus in New York, Colorado, and Texas noted the onset of a new depression, with 75% of these individuals displaying Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scores suggesting mild to severe depression levels.

In 2017, a study in Kenya, an area endemic to malaria, discovered that having malaria parasites in the blood was linked to higher chances of common mental disorders (CMD), but not connected to higher rates of other problems like psychotic symptoms, ADHD, PTSD, alcohol use, risky drinking, or thoughts of suicide.

Researchers in Sri Lanka discovered that people who had dengue (mosquito-borne viral disease) before showed significantly more signs of feeling depressed, anxious, and stressed. An earlier study in Pakistan revealed that “a majority of patients with dengue have anxiety and depression symptoms.”

The prevalence of mental health issues with vector-borne diseases is one issue. Another is how disproportionately it affects certain groups.

Healthcare disparities among Indigenous communities

In the heart of lush landscapes, a quieter story unfolds, one that speaks of the deep impact of deforestation on indigenous communities. These communities, guardians of delicate ecosystems, find themselves grappling with the health consequences of ecological disruption.

While there is a vast amount of research on how deforestation affects public health in general, less is known about its impact on vulnerable groups who often live closest to the forests.

Many indigenous communities make their homes in tropical forests, which are the very places most susceptible to new diseases. About 36% of the remaining untouched forests globally, with half located in tropical regions, are on indigenous lands. These communities are responsible for protecting approximately 80% of the Earth’s remaining biodiversity. Forests on Indigenous lands are better cared for and have more diverse plants and animals than forests in non-Indigenous areas.

Back in 2020, when the world was battling with the COVID-19 pandemic, a study by Humberto Laudares, PhD in Global Health, and Pedro Henrique Gagliardi, linked deforestation to the transmission of COVID-19 within indigenous communities in Brazil. The researchers found that the deforestation of a square kilometer one day would lead to a 9.5% increase in new COVID-19 cases within a span of two weeks.

“The evidence suggests that the main mechanisms through which deforestation intensifies human contact between indigenous and infected people are illegal mining and conflicts,” the authors concluded.

International policies and conservation efforts

At the end of the last century, amidst the echoing chainsaws and the rapid expansion of farms and roads Costa Rica’s vast forests were becoming fragmented. The habitats that provided sanctuary to countless species were changing into farmlands and industrial infrastructure. By 1987, the country had lost half of its forest, but change was around the corner.

Costa Rica managed to shift its course of history through a series of innovative policies, including a ban on forest clearance without authorization, and payments to local communities to help protect the ecosystem. About 20 years later, Costa Rica became the first tropical country that has not only stopped, but has reversed, deforestation.

Today, almost 60% of the land is covered in forests, housing around half a million plant and animal species.

Now, other nations are taking action to follow Costa Rica’s example. In 2020, more than 100 world leaders promised to reverse deforestation by 2030 with $19.2billion of public and private funds issued. The new pledge was welcomed with a hint of suspicion, considering the last one in 2014 failed to deliver on key components.

One approach gaining traction involves the promotion of sustainable practices. This means producing commodities such as timber, beef, soy, palm oil, and paper in a manner that avoids contributing to deforestation and has a minimal effect on our climate. For example, in 2022, the EU agreed that goods introduced to the EU market would cease to play a role in causing deforestation and forest degradation, whether within the region or on a global scale.

Sustainability has been the focal point in many international policies and conservation efforts, including UN-REDD – the United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. In Vietnam, UN-REDD provided assistance to shrimp farmers in creating an organic farming approach that safeguards delicate mangrove forests. In Nigeria, UN-REDD initiatives advanced forest management and the preservation of biodiversity, leading to better rural livelihoods.

While there are many conservation efforts to halt deforestation, only a few are integrated with public health concerns. Existing strategies for pandemic readiness focus on managing diseases once they have surfaced. Despite mounting research connecting deforestation with outbreaks, this perspective remains strong.

In the wake of COVID-19’s worldwide impact, the Biden administration’s pandemic readiness strategy, disclosed in September 2021, acknowledged habitat loss and human behavior as contributing factors to an increased number of zoonotic diseases. But the annual report published a year later didn’t list any actions to reverse deforestation.

The International Health Regulations (IHRs), a framework endorsed by the WHO to manage infectious risks across approximately 200 nations, predominantly rest on the premise that disease outbreaks are not preventable, only manageable and extinguishable.

Many think that stopping deforestation is a very difficult problem and would use up the little money available to fight pandemics. Experts at the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response argued in 2022 that the numerous actions and measures needed to prevent spillover are almost impossible, much like trying to do something as vast as “boiling the ocean.”

On the other hand, a recent study co-authored by Aaron Bernstein from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health suggests preventive measures, like providing financial support for forest protection and implementing regulations to halt the trade of species with the highest potential for spreading diseases from animals to humans, could be achieved with an annual budget as low as $22 billion – about 500 times less than the cost of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“When you think of the cost-benefit of how to really save the health of most people it’s really forest conservation, environmental conservation, not going in and eating wildlife, and that’s really the most cost-effective public health benefit,” Mary Pearl said while talking on a webinar from Rainforest Alliance in 2020.

One organization may have figured out the way forward by combining conservation and health efforts with a human-centered approach.

It all started with Dr. Kinari Webb who spent years working in forests in Borneo, the third largest island in the world, located in Indonesia. She heard and saw all of it: the chainsaws, wood piled up, and the forest that was degrading. For years, local communities in the region used to illegally cut down trees, to provide food and income for their families. Then she did something that wasn’t typical – she asked the loggers why they cut down trees and what they needed to stop logging – and decided to listen to their expertise.

For the next 18 years or so, listening to local communities and indigenous people has become the core foundation of the organization she started. Health in Harmony is a U.S.-based nonprofit that works with communities in Brazil, Indonesia, and Madagascar to yield a decrease in deforestation rates and simultaneously enhance the quality of life for local people.

The way they do it is through improving access to healthcare, supporting livelihood, and providing education. In Brazil for example the organization had a motored canoe that would deliver healthcare to the most remote communities. In Indonesia, they provided support with organic farming training.

The research discovered that Health in Harmony’s approach of engaging with rainforest communities directly resulted in a 70% decrease in deforestation in Gunung Palung National Park in Indonesian Borneo and a 90% decrease in the number of households depending on logging as their main income. As of June 2023, about 365 hectares have been reforested in the organization’s working areas in Brazil, Indonesia, and Madagascar. Health In Harmony’s investment of $5 million over a decade ultimately led to the avoidance of $65 million worth of carbon dioxide emissions.

Working with indigenous communities, like the ones living in Borneo, is what many experts think could lead to solutions for stopping deforestation and preventing pandemics.

“There is evidence that indigenous people are good at what they are doing. It’s their lands after all,” Fa said.

As Dr. Paula Prist of EcoHealth Alliance notes, supporting indigenous communities to protect their forests is urgent not “just for their survival and the long-term health of the planet, but also for another very simple reason — so that they and millions of other people can breathe,”

While some efforts have been made, the pressing need for many more remains apparent. The challenges we face in terms of ecological balance, disease prevention, and the overall well-being of our planet are far from resolved. “I don’t want to be scary but it is perhaps inevitable that a disease, say as contagious as measles and as lethal as Ebola could emerge. This is in the realm of possibility and that’s why it’s so urgent for us to get smart about managing our planet,” said Pearl.

*References can be found here.