mosquito control

The Drone Edge in Vector Control

Achieving global vector control’s potential requires “realigning programs to optimize the delivery of interventions that are tailored to the local context [and]…strengthened monitoring systems and novel interventions with proven effectiveness.” This includes “integration of non-chemical and chemical vector control methods [and] evidence-based decision making guided by operational research and entomological and epidemiological surveillance and evaluation.”

Drones or “unmanned aerial vehicles” (UAVs) can save time and money compared to conventional ground-based surveys. Sophisticated models and monitoring equipment can be purchased for a few thousand dollars. They don’t require a pilot’s license, they are becoming easier to fly, and their paths can be fully automated through AI, machine learning, global positioning systems, and computer vision.

Mosquito Control Drone Application

Check out this video from Calcasieu Parish Mosquito and Rodent Control on how they are using drone technology to spray in hard to reach areas and increase the efficiency of eliminating disease-carrying populations of mosquitos.

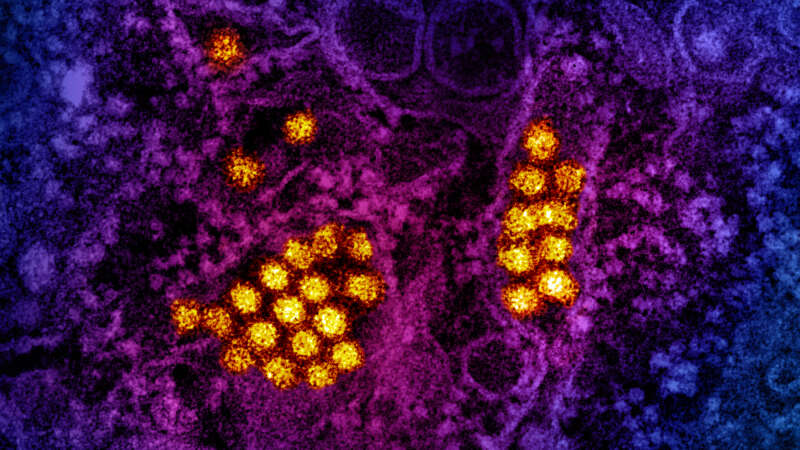

The Rise of Dengue: A Global Perspective

Around the world, dengue is considered the most common viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes that affects people. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries. In the first three months of 2024, over five million dengue cases and over 2000 dengue-related deaths were reported globally. The figures so far project that 2024 could be even worse than 2023, with the regions most seriously affected being the Americas, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific.

In the Americas, there were 6,186,805 suspected cases of dengue reported in the first 15 weeks of 2024. To put this into perspective, according to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), this figure represents an increase of 254% compared to the same period in 2023. Of these cases 5,928 were confirmed and classified as severe dengue.

Peter DeChant: Vector Control Visionary

The story of Peter DeChant, a veteran in the mosquito and vector control profession whose journey spans over four decades, is one of dedication, innovation, and relentless commitment to combating mosquito-borne diseases.

Peter’s journey began in 1978 when he became a field technician with Multnomah County Vector Control in Portland, Oregon. Little did he know then that this would mark the start of a lifelong crusade against one of the deadliest creatures on the planet.

By 1983, Peter’s skills and passion for his work led him to the role of Chief Sanitarian, where he led the program for 14 years. It was during this time that he honed his expertise and laid the foundation for his future endeavors.

The Economics of Resistance

It would be extremely difficult to calculate, with any high degree of accuracy, the global economic impact of insecticide resistance. For starters, we must consider that insect management plays a pivotal role in a variety of sectors – agriculture, home and garden, forestry, structural applications, and vector control. Analysis of the totality of economic impacts arising from resistance in any one of these sectors quickly becomes a complicated interplay of variables that interact within that given system.

To account for the full economic impact, one must layer in the amount being spent on insect management and how much of that investment is lost to resistance, but also the economic impact of losses to the overarching objectives of a given program.

To calculate the impact, you must first calculate what is at risk.

How Does Insecticide Resistance Happen?

Check out this video by MalariaGen focusing on how natural selection drives insecticide resistance relating to malaria.

Avian Malaria in the Sub-Antarctic

Avian malaria has recently been discovered in southern Chile and the introduction of beavers decades ago is partially responsible.

Birds on the Brink

Hardly anyone visits the desolate outpost of Coldfoot, one of Alaska’s few communities outside the Arctic Circle accessible by road. Its 34 residents live in rustic accommodations along the Dalton Highway. The town’s highlights include an inn, a café, a gas station and a basic airport with a gravel landing strip. All day long, 18-wheeler fuel trucks thunder by on supply runs between Fairbanks and the oil fields of Prudhoe Bay further north. Some will stop to eat and tank up at Coldfoot because the next human habitation is 234 miles away, a town grimly named Deadhorse.

They say Coldfoot got its name from the days of the 1900 Gold Rush when miners would come as far as this remote settlement before getting “cold feet” and turning back. It’s still a lonely place, but one unexpected visitor showed up recently inside an infected Swainson’s thrush (Catharus ustulatus): the avian malaria parasite, Plasmodium circumflexum.

In 2011, scientists tested 676 birds representing 32 resident and migratory bird species captured from three northern locations in Alaska: Anchorage (61°N), Fairbanks (64°N) and Coldfoot (67°N). In Anchorage and Fairbanks, they found 49 birds infected by Plasmodium parasites. In Anchorage, even resident birds and hatchlings of species such as the boreal chickadee (Poecile hudsonicus), the varied thrush (Zoothera naevia) and the fox sparrow (Passerella iliaca) were found infected. The parasite was also detected in black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) and a myrtle warbler (Dendroica coronata coronata) in Fairbanks, indicating that transmission had occurred locally.

Vanishing Birds

If you were alive in the year 1970, more than one in four birds in the U.S. and Canada has disappeared within your lifetime.

According to research published online in September by the journal Science, wild bird populations in the continental U.S. and Canada have declined by almost 30% since 1970.

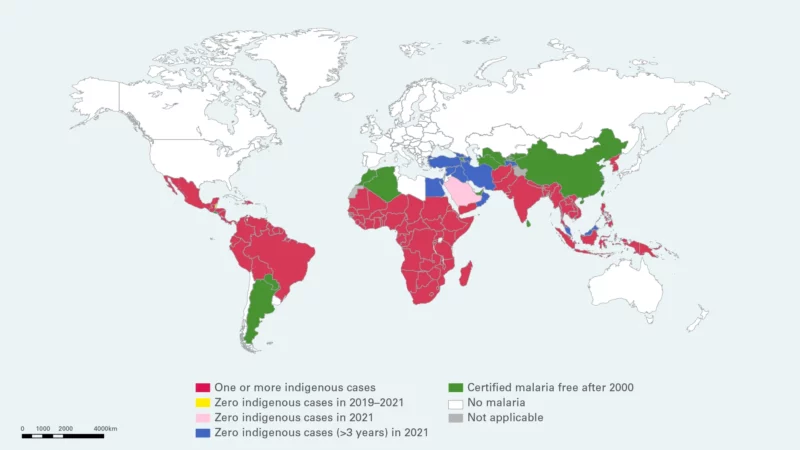

Malaria by the Numbers

According to the 2022 World Malaria Report, despite disruptions to prevention, diagnostic and treatment services during the pandemic, countries around the world have largely held the line against further setbacks to malaria control.

Good news:

Progress towards malaria elimination is increasing; in 2021, there were 84 malaria endemic countries compared with 108 in 2000.