Merck’s commitment to donate ivermectin for onchocerciasis control in the late 80s was only the beginning of the challenge to deliver the intervention to those in need.

When Merck announced on October 21, 1987 that it would donate its powerful anthelmintic drug ivermectin for onchocerciasis control for as long as needed, the commitment was unprecedented. Not only would the term of the donation span decades, the number of individual treatments would ultimately rise into the billions.

Still, the availability of ivermectin free of charge for millions who needed it was just the first step in administering the therapy. While the financial implications of such a donation for a Private entity such as Merck cannot be overstated, perhaps more important was the resultant development of public and private partnerships for distribution of the drug that has delivered benefits that would eventually extend well beyond the Onchocerciasis Control Programme (OCP).

People over Profit

Partners in Progress Series

When Merck began development of what would become the avermectin family of chemicals, its initial target was animal health. Ivermectin (Ivomec) first entered the market in France in 1981 as a veterinary therapy to control parasitic worms in cattle, horses, pigs, sheep, and dogs. By the time Mectizan® was introduced six years later, ivermectin was the second bestselling active ingredient in the company’s expanding portfolio.

The pre-existing profitability of the drug in the animal sector surely played into the company’s decision to donate the drug for onchocerciasis control, since the people who most needed Mectizan were too poor to pay for it. Originally developed for use in hospital environments, the effectiveness and safety of the drug – combined with the limited ability of vector control to combat the disease as a stand-alone – led Merck leadership to switch their focus to donation and mass distribution.

The challenge then became how to get the drug to those who were at risk or infected. In late 1987, the company launched the Mectizan Donation Program (MDP) to establish the partnerships necessary to develop and oversee such a process. As a start, Merck reached out to the Task Force for Child Survival and Development, a non-governmental organization (NGO) with mass distribution experience. With the NGO’s help, the Mectizan Expert Committee was established in 1988 to begin the process of building out MDP’s structure. The team also sought input from existing blindness organizations such as Helen Keller International and Sight Savers that were already conducting operations in endemic onchocerciasis communities.

The basis of the program was that Merck would be responsible for the manufacturing and delivery of ivermectin to NGOs, which would then be responsible for getting the drug into the hands of distributors who in turn would deliver it to communities in need. Prioritization was critical to success. As an early step, the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) developed a tool called rapid epidemiological mapping of onchocerciasis (REMO) that OCP personnel could use to quickly determine which communities were at highest risk for the disease.

If You Build It

By 1991, under MDP, the myriad of NGOs and private donors now on board with the program were striving to develop more efficient systems for distribution through numerous regional and local programs. In the initial stages of these programs, Mectizan was delivered directly to West African communities by mobile clinics staffed by NGO, government, OCP, and health personnel who administered the drug and educated the public on its use and benefits. While the mobile clinics were reasonably effective, the approach was costly and lacked the financial and human resources necessary to achieve ivermectin coverage on a large scale. Moreover, it quickly became obvious to organizers that the communities themselves needed to be intimately involved if the program were to be successful.

Ivermectin and its distribution were generally accepted in the region, but there were challenges. For one thing, there was underlying skepticism about the drug. Dietheylcarbamazine, a drug used for lymphatic filariasis, had been used for onchocerciasis but had limited effectiveness along with a range of side effects such as severe itching, facial swelling, headaches, and loss of energy. Many anticipated that ivermectin would have the same issues.

But when individual communities were encouraged to become involved in the planning and execution of the new programs, they gained a sense of ownership that promoted awareness, accountability, and accomplishment as the effects of the program became clearly visible. For example, rather than having local distributors selected by other entities in the partnership, program leaders encouraged treated communities to appoint their own distributors. Likewise, the actual administration of the drug was typically undertaken by individuals within the community.

Using this approach, NGOs were able to transition from being distributors to providing training and support to community-directed programs, and over the course of the next years 15 years, “community-directed treatments with ivermectin,” or CDTI, would become the backbone of ivermectin distribution.

The overarching process was easy to follow, if challenging to implement. Regions would apply to NGOs for ivermectin treatment programs, and once approved, program leaders would meet with local communities to educate them and lay groundwork for distribution. The community would select its own distributors, who would then receive training. An important next step was to conduct an accurate community census in order to ensure that sufficient supplies were delivered.

Once a treatment date was agreed upon, distributors would connect with local health workers and provide the ivermectin tablets. These workers would administer the drug, keep accurate records, and monitor patients’ reactions in order to accurately report on program outcomes.

Navigating Challenges

While the ultimate success of ivermectin, MDP, OCP, and later the African Program for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) and the Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas (OEPA) are well documented, those successes did not come without significant hurdles.

Financial sustainability, as usual, topped the list. Despite Merck’s willingness to gift ivermectin and contributions from the many private donors in the partnership, regional and local governments and ministries of health often lacked the resources to fully fund their own program activities. This challenge was exacerbated as the effects of ivermectin distribution became apparent and demand for more programs grew. Since money was changing hands at multiple levels of distribution, potential for corruption and the misuse of funds was a constant concern. Funding also faced challenges from competition from other health programs such as Roll Back Malaria and Stop TB.

Effective planning and program execution also varied by community. Support was typically high in endemic communities, but not every government and program enjoyed the same levels of expertise and commitment. When a local census was conducted haphazardly, distributors found themselves in short supply of ivermectin on treatment dates, and fulfillment of new orders took as long as four months.

Monitoring, record keeping, and reporting – of indispensable value to programs – could also be labor intensive, especially with obstacles like literacy and experience working with numbers. Political unrest, unstable governments, and transitions in leadership could also stall programs. Even getting ivermectin through customs could prove challenging on occasion.

And while the ultimate objective of every program was full integration with local health services, this too could prove problematic. For health systems that were already strained, layering on another program was a challenge. This was especially true where treatment areas were remote and lacked the infrastructure necessary to promote coordination with these services, as paved roads and telecommunications were sometimes absent.

Perspective for the Pandemic

The recent announcements surrounding the anticipated approval of COVID-19 vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna seemed to lift the collective spirits of a global community that has been burdened by the unprecedented effects of the pandemic for almost a year.

At the same time, the promise of a potential intervention has been tempered by questions from both the health care industry and the community at large. It is no coincidence that many of the challenges being raised are similar to challenges that hindered successful implementation of mass distribution of ivermectin in Africa and Latin America for onchocerciasis control over the past three decades. Some key examples:

VOLUME – More than 2 billion ivermectin tablets were delivered as part of the Mectizan Donation Program over the course of 30-plus years. The magnitude of undertaking a global vaccination program like the pending vaccines is daunting. Considering a current global population of 7.8 billion – and two rounds of vaccinations for each individual (both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccine require individuals to get two shots, weeks apart) – the total number of treatments required would rise to 15.6 billion. Putting that number in perspective, if 1 million doses were administered globally every single day, it would take more than four years to vaccinate the world population. Thought of another way, more than 42 million vaccinations per day would be required to treat the entire population within one year.

LOGISTICS – The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are just two of several potential interventions in development. As experienced across a myriad of Onchocerciasis Control Programs, manufacture of the intervention is only the beginning. Layering a multi-step delivery program, materials security, training and retraining of personnel, monitoring, and reporting into the equation, activities relating to that volume become staggering. CDC’s “playbook” for a COVID-19 Vaccination Program can be found here.

ACCEPTANCE – As was the case with ivermectin, gaining public acceptance of an intervention is not as easy as it sounds. While the whole world hopes for a viable COVID-19 solution to emerge, there remains a significant amount of skepticism surrounding fast-tracked vaccines among both the general public and health care workers. A Harris Poll conducted October 7-10 revealed that less than 60% of Americans indicated they would get a vaccine as soon as one was ready. Moreover, an October survey of 13,000 nurses conducted by the American Nurses Foundation revealed that 40% of nurses lack confidence in the accelerated development process and that 44% of respondents would be uncomfortable talking about a vaccine with patients.

COMPETING DEMANDS – Competing demands from other programs and responsibilities was a challenge for the Onchocerciasis Control Programme, and will be again with COVID-19. In addition to their reservations about the viability of whatever vaccines are put in place, health care workers will have to add those vaccination activities to a workload already burdened by treating COVID patients.

On a positive note, one needn’t look further than the example of onchocerciasis control to realize what is possible when fully committed public and private partnerships mobilize. Just as the scale of our battle against COVID-19 far eclipses what took place with onchocerciasis, so too does the predominance of our awareness and commitment to defeating Coronavirus.

Impressive Outcomes

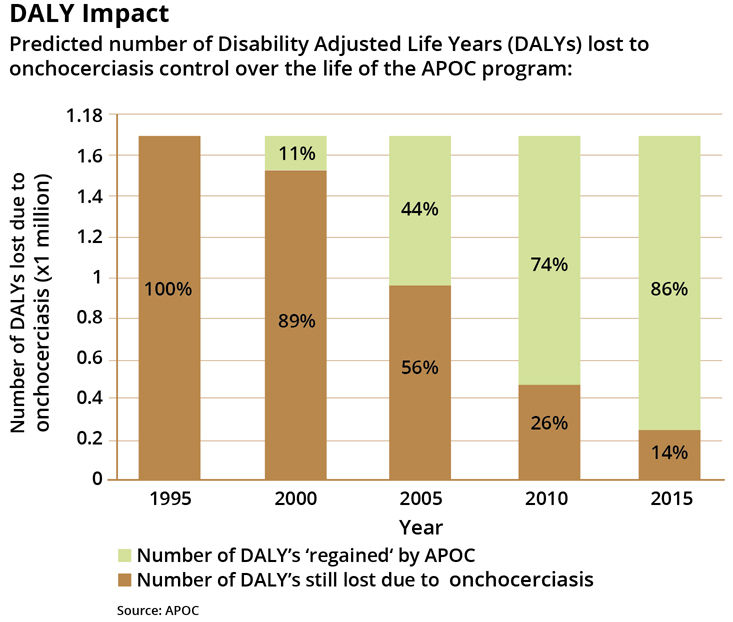

These same challenges make the far-reaching effects of onchocerciasis control programs in Africa (and later Latin America) all the more impressive. By 2010, APOC was overseeing 50 million annual treatments of ivermectin. By the time the program officially ended in 2015, that number had doubled to more than 100 million.

While blindness caused by onchocerciasis is irreversible, trends in blindness are not. APOC estimates that the incidence of blindness in affected areas has dropped to 32% of pre-CDTI levels. Onchocerciasis infection declined by an estimated 86%.

The indirect effect of these efforts is especially relevant today. Now established, the CDTI approach has been used to support other important public health initiatives such as immunization programs and mosquito bed net distribution. Moreover, the infrastructure to support these programs in affected areas has greatly improved. Such astounding achievements have arisen from the simplicity of a beneficial microbe, the magnanimity of a corporate gift, and a public and private partnership of unprecedented scale.

Ivomec® and Mectizan® are registered trademarks of Merck & Co., Inc.