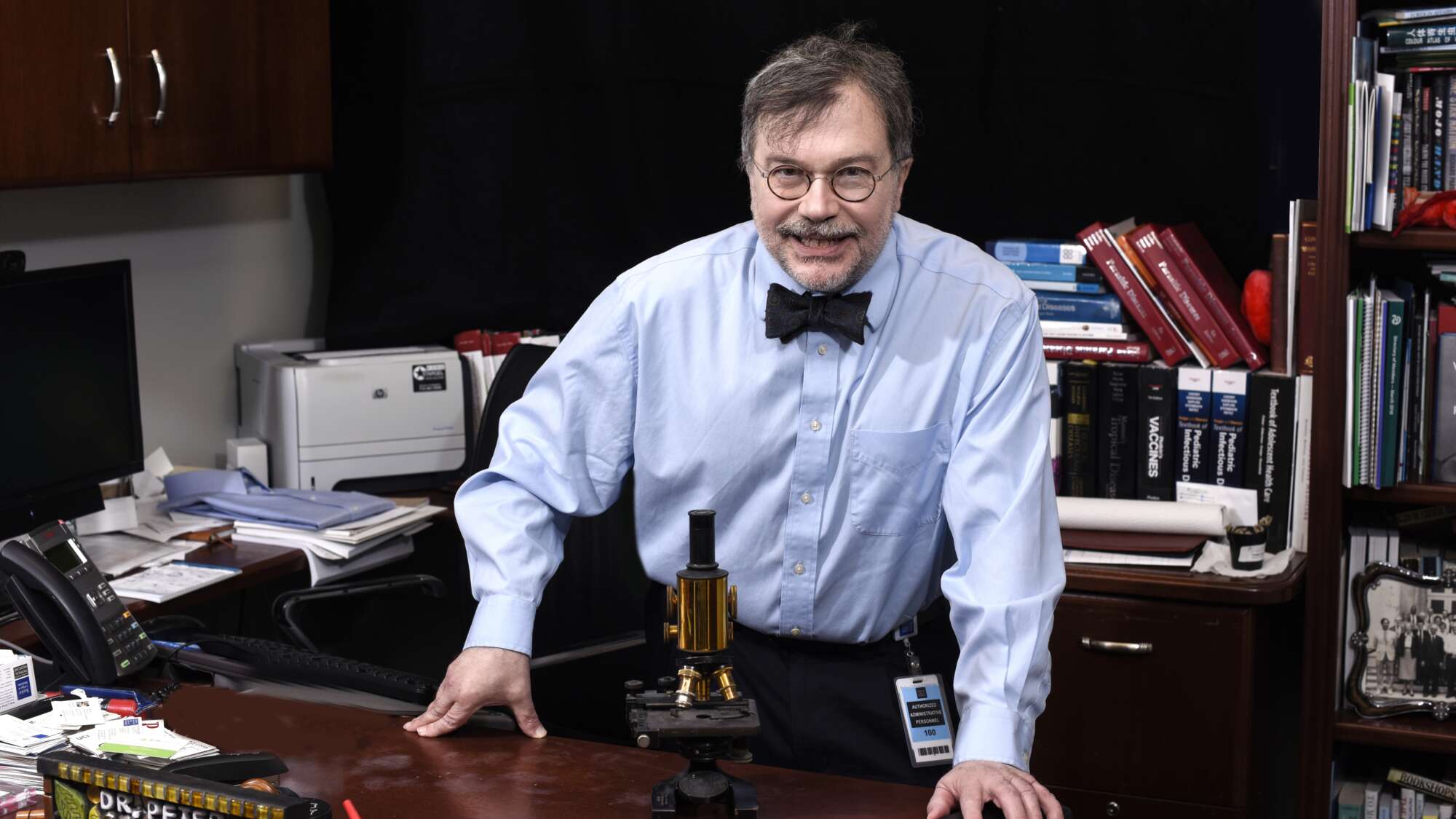

Dr. Peter J. Hotez is a physician-scientist who dedicates his career to fighting neglected tropical diseases and vaccine development. He is the Dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine and a professor at Baylor College of Medicine, where he also serves as the Co-director of the Texas Children’s Center for Vaccine Development (CVD) and the Texas Children’s Hospital Endowed Chair of Tropical Pediatrics.

Dr. Hotez is an internationally recognized expert in his field, leading a team and product development partnership for new vaccines for diseases such as hookworm infection, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, and coronaviruses, which affect millions of people worldwide. He is committed to championing global access to vaccines, including leading efforts to develop a low-cost recombinant protein COVID vaccine resulting in emergency use authorization in India.

Dr. Hotez’s educational background includes an undergraduate degree in molecular biophysics from Yale University, a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Rockefeller University, and an M.D. from Weil Cornell Medical College. He has authored over 600 original papers and is the author of five single-author books.

In addition to his work at Baylor College of Medicine, Dr. Hotez has served as the President of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, founding Editor-in-Chief of PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, and an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine and the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. He served in the Obama Administration as US Envoy, focusing on vaccine diplomacy initiatives between the US Government and countries in the Middle East and North Africa, and was appointed by the US State Department to serve on the Board of Governors for the US Israel Binational Science Foundation.

Our purpose has never changed – to bring attention to the neglected diseases of poverty and build a new generation of vaccine in the pursuit of global vaccine diplomacy.

Dr. Peter J. Hotez

Dr. Hotez is a vocal advocate for vaccines and has received recognition for his leadership and advocacy efforts in this area, including awards from the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, the AAMC, the AMA, and the Anti-Defamation League. He frequently appears in media interviews to discuss his work and the importance of vaccines.

Dr. Hotez’s dedication to global health and vaccine development has led him to be nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022, along with his colleague Dr. Maria Elena Bottazzi, for their work in developing and distributing a low-cost COVID-19 vaccine without patent limitation.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this interview are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Public Health Landscape or Valent BioSciences, LLC.