In the 2022 World Malaria Report, compiled by the World Health Organization (WHO), the total spend on funding the fight of malaria in 2021 was estimated at USD 3.5 billion1. Over that year, the same report states that there were an estimated 247 million cases of malaria and 619,000 malaria deaths globally.

Man’s battle against malaria has endured for millennia with economic and socially devastating effects on empires, regions, countries, communities and families. Ancient civilizations of China, Mesopotamia, Egypt, India and Greece have documented and revealed evidence of outbreaks and struggles with the disease2. The malaria antigen was detected in Egyptian remains dating from 3200–1304 BCE3 and potentially led to the death of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun4. During the Vedic period (1500–800 BCE) Indian writings referred to malaria as the ‘king of diseases’ and many ancient Greek scholars documented the disease with Homer mentioning malaria in his book The Iliad (c. 750 BCE). The disease has also been speculated as a possible contribution to the fall of the Roman Empire5.

Oregon State University

More recently, over the course of the 20th Century, malaria is believed to have claimed between 150–300 million lives6. The disease is contracted predominantly in the tropical regions: sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and the Amazon basin. This is due to the prevalence of the Anopheles mosquito that transmits the disease. Poorer regions of Africa bear the vast majority of the burden. In 2021, around 95% of the diagnosed cases and deaths were on the African continent, 80% of which were children under the age of five7. The disease is entirely preventable and curable with prompt diagnosis and effective methods of treatment which require sufficient investment and funding.

The Global Burden of Malaria

Malaria is transmitted through the bites of female Anopheles mosquitoes. There are five species of parasites that cause the disease with two of these, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, posing the greatest threat to humans. The parasite is found in the red blood cells of an infected person so the disease can also be transmitted through blood transfusion, organ transplant or the shared use of contaminated needles or syringes. A mother can also pass the disease onto her unborn infant before or during delivery.8

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

Once the parasite enters the bloodstream it can take around 10 days for symptoms to appear, however some people may start feeling ill one year later as many people are carriers without realizing. Symptoms can vary from person to person but usually they are flu-like: fever, body aches, vomiting and chills. Without treatment, the disease can progress to very severe or cerebral malaria – once a person reaches this stage, even after anti-malarial treatment, the mortality rate can be as high as 20% to 25%9.

The disease is a huge drain on many national economies because it causes so much illness and death. Countries with the disease are already among the poorer nations which maintains a vicious cycle of poverty.10

Why is it a Global Issue?

In 2015, the WHO launched the Global Technical Strategy (GTS) for malaria 2016–2030 and it was adopted by the World Health Assembly. The comprehensive framework offers a guide to countries to accelerate progress towards eliminating the disease. The GTS includes estimates for the funding required to achieve key milestones in 2025 and 2030, and states that investment in malaria (both international and domestic) needs to increase substantially above the current annual spending.11

Although total funding in 2021 was estimated at USD 3.5 billion, an increase from the USD 3.3 billion in 2020 and USD 3.0 billion in 2019, this is still short of what the GTS projected would be required to successfully reduce and eliminate the disease.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is a big donor to the fight against malaria (2% of global R&D funding between 2010–202112). The foundation believes that the fight against malaria is a global one. On the foundation’s website is a statement by Melinda French Gates: “Any goal short of eradicating malaria is accepting malaria, it’s making peace with malaria, it’s rich countries saying, “We don’t need to eradicate malaria around the world as long as we’ve eliminated it in our own countries”.” The foundation states that as long as malaria exists, it will be an engine of inequality, burdening the poorest and most vulnerable communities and it will have the potential to resurge in times of crisis13.

The main challenges that the world faces in the attempt to wipe out malaria can often be attributed to insufficient investment. The true cost of the disease and the intricate relationship between malaria and economics – the direct and indirect costs – is difficult to quantify but is key to ensuring its successful eradication.

The Costs of Malaria

In countries where there are fewer cases of malaria, the costs to the economy can be quantified in a more straightforward manner – simply accounting for the average cost of an individual episode of the illness, multiplied by the total number of cases encountered, and adding any fixed costs expended in prevention and treatment of the disease14. In countries where the rate of transmissions and cases are high, this method cannot be used to determine the true cost of malaria to the economy.

In these cases, both the direct and indirect costs that are incurred by individuals, upon households, local communities, industries and the general GDP of a country must be assessed.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total of all value created in an economy; the value of goods and services that have been produced minus the value of the goods and services needed to produce them. GDP also includes estimates of an informal economy – the unreported cash transactions which can also include illegal trade – this is a challenge for economists to calculate15.

The first infographic below represents data compiled from multiple sources by the World Bank which shows the GDP per capita (economic output per person) of countries across the globe from 1990–2021. The second infographic is a map showing the number of deaths from malaria per 100,000 people from 2000–2020, using data sourced by the WHO’s Global Health Observatory in 2022.

The two interactive maps indicate that there is a correlation between the malaria deaths and a country’s GDP. This may reflect a number of scenarios: the disease may cause poverty by impeding economic growth; poverty may promote malaria transmission; or both could be true.

Direct Costs of Malaria

These are some of the main direct costs that are covered either privately or publicly by households, districts, a country and/or a region16:

- Resource allocation

- Drugs and vaccines

- Vector control

- Diagnostics

- Biologics (biological control agents, such as parasites, pathogens and predators that can be used to target various life stages of the mosquito)

- Implementing technology for data collection

- Surveillance (equipment and assessments)

- Healthcare expenses

- Ongoing investments in research and development R&D

Harry Weinburgh, CDC

Indirect Costs of Malaria

Yirla Marcela Becerra is a habitant of Tutunendo, a remote location within the tropical rainforest in the department of Chocó, Colombia. In an interview for the Pan American Health Organization she describes her experience of contracting malaria and the impact it can have on a person’s life within her community, “I have had malaria. You feel unwell, you go to sleep because you feel sick. You can’t do your household chores, sometimes you lose your job because you are sick and you can’t go.17“

Yirla’s experience describes some of the indirect costs that sufferers of the disease face, but there are many other indirect costs to consider.

- Deterrent to investors – the presence of malaria in a community or country hampers individual and national prosperity due to its influence on economic decisions from both internal and external investors

- Lost productivity or income – cost of lost workdays or absenteeism from formal employment and the value of unpaid work done in the home by both men and women

- Damage to industries – the presence of the disease can cause a deterrent in tourism and impact trade

- Loss of future earnings – the death of a household member can cause an impact on the prosperity of the rest of the family into the future18

- Education and social development – children’s development through both absenteeism and permanent neurological and other damage associated with severe episodes of the disease19

- Altered behaviors and decision making – for example, farmers may plant subsistence crops rather than more labor-intensive cash crops because of malaria’s impact on labor during harvest season. This can affect economic productivity and growth.

Economic Analysis

Doing an analysis of the economic and financial cost and return of malaria control, elimination and eradication is a complex undertaking. Decision makers need to determine if the benefits of funding continued methods to merely control the disease – to prevent an outbreak and create a decline in transmission and death rates – or if it would be more cost effective in the long run to fund a program of elimination.

There are different methods of economic analysis used to determine the value of investing in the advantages of elimination versus the ongoing control of malaria in a given country or region. For economic evaluations to aid decision making, particularly if the aim is the elimination of the disease, two aspects must be addressed: the long-term effects of the policies and their impacts beyond health (for example to industry, education, an individual’s income); and to fully reflect the benefits of malaria elimination, it would be necessary to estimate the long-term benefits of a scenario with no malaria20.

A cost-benefit analysis compares projected or estimated costs and benefits associated with a project to determine whether it makes good economic sense. If the projected benefits outweigh the costs, key decision makers would tend to believe that investing in the project would be a good choice21.

In order to conduct a cost-benefit analysis a framework must first be established, the costs and benefits must be identified with a financial value assigned, tallied and compared. There are many pros and cons to this approach.

A data-driven approach offers an evidence-based evaluation – if the data is well selected and collected. This type of approach can make decision making less complex and more compelling if the evidence found is favorable to the project going ahead, however the human element, especially in the controlling of a disease can be forgotten when the findings are not favorable. There can be difficulties in predicting all of the variables and putting a value to them, especially on a longer-term basis. For example, costs for materials may sky-rocket if there is a conflict or supply shortage (such as what has happened recently as a result of the war in Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic22/23), equally an influx of migrants due to a humanitarian crisis may also dramatically change the costs of initiatives (such as what has happened in Brazil and Colombia with an influx of migrants and refugees from Venezuela24).

In order to do a cost-benefit analysis it is essential to understand the dynamics of the community, country or region in question. Benefits to an industry such as tourism, as a result of eliminating the disease, may be difficult to predict as it may still be affected by other factors. By including the potential impacts beyond health in an economic evaluation could provide useful information to decision-makers across different sectors25, which could attract more funding and investment.

A robust analysis requires the ability to obtain reliable data and the parameters of the benefits to include both the direct and indirect costs of the disease, and likewise the direct and indirect benefits. The inclusion of factors such as the impact on education outcomes, or on human capital accumulation, hasn’t been explicitly considered in the economic evaluation of public health malaria interventions conducted within the healthcare sector, which could potentially misrepresent the full impact of malaria prevention interventions26.

Image Courtesy: tpsdave

A study led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs in 2020, calculated that eliminating malaria in Ghana would cost USD 961 million over the course of a decade (2020–2029). This investment would prevent an estimated 85.5 million cases, save 4,500 lives and avert USD 2.2 billion in health care expenditures.27 The benefits would be lowered health system expenditures, increased household prosperity, reduced absenteeism and productivity gains due to a dramatic reduction in malaria cases. Although the initial investment seems colossal, the assessment was that the country could expect a 32-fold return on the investment.

Similarly, in 2021, a cost–benefit analysis of malaria elimination in South Africa was done to assess three different scenarios aimed at achieving malaria elimination within a 10-year period. The report found that malaria elimination in South Africa would be feasible and economically worthwhile with a guaranteed positive return on investment. The three scenarios were: Business as Usual which would cost USD 223.3 million over an 11-year period, Accelerate Reduction at a cost of USD 295.5 million and Source Reduction ~USD 384 million. The country could eliminate the disease in eight years if funding could be secured to support the proposed interventions in the endemic areas of South Africa and neighboring Mozambique.28

Factors Amplifying the Spread

There are many factors that amplify the spread of malaria. It is essential to monitor and understand these variables in order to best direct spending in an effective manner.

Biological Factors

According to the WHO, the main biological threats to malaria interventions are considered to be29 :

- Antimalarial drug efficiency and resistance

- Deletions in P.falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 and protein 3 genes

- Vector resistance to insecticides

- Anopheles stephensi invasion and spread

- Effectiveness of Insecticide-Treated Mosquito Nets (ITNs)

- Effectiveness challenges related to Indoor Residence Spraying (IRS)

Non-biological Factors

Mosquitos that transmit the disease thrive under certain conditions. Changes in these conditions can increase the spread and/or reduce the efficiency of control methods.

- Climate – temperature, rainfall and humidity

- Water quality and temperature – development of mosquito larvae

- Global warming – and other long-term occurrences such as El Niño cycles that change habitable zones

- Deforestation – change in habitable zones for mosquitoes and human and animal population change of an area

- Rapid unplanned urban development – can create new breeding grounds

- Agricultural practices – including the building of dams and irrigation schemes, can create new breeding grounds

- Population movement and migration – a lack of knowledge and immunity in people moving from an area that didn’t have mosquitoes (ie/ moving from highlands down into marsh lands) and bringing infections to a new area that previously was without

- Population displacements – lack of basic healthcare, poor living conditions, malnutrition, lack of access to preventative tools

- Lack of data collection – difficulty in monitoring outbreaks

- Humanitarian crisis – conflicts, wars, pandemics and natural disasters can increase costs, prevent access and distribution channels

From an economic perspective many of the variables on the above list are difficult to monitor and quantify. There are many crossovers – so it can be a complicated task to predict the changes and project future costs.30

Prevention and Control Efforts

In the past, many of today’s wealthier countries suffered from malaria. However, countries across Europe31 and the U.S.32 successfully eliminated malaria in the 20th Century. This was a result of both socioeconomic development and intensive anti-malaria interventions and investment.

![Sergeant James H. Johnson, Pittsburg, MS (right) instructs Sergeant 1st Class Jack Frederick, Wellsville, IL (center) and Sergeant Teddy Sadlocha, Hamtramck, MI (left), members of Medical Detachment, United States IX [9] Corps, in the use of the DDT sprayer. Korean War. 8/15/1951 Otis Historical Archives of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, in Washington DC.](https://publichealthlandscape.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2124122193_6447ff9cd7_o-800x655.jpg)

Otis Historical Archives of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, in Washington DC.

The disease was endemic in the U.S. until the 1950s. In 1942, the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas was established to limit the impact of malaria during the Second World War around military bases in southern U.S. states. After the war the national public health agency, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was formed and launched the National Malaria Eradication Program which combined the efforts of state and local health agencies of 13 southeastern states and the Communicable Disease Center of the U.S. Public Health Service. Within five years a program of prevention and control methods including: applying DDT insecticide to 4,650,000 houses in rural areas, the removal of mosquito breeding sites and the spraying of insecticides using, at times, aircrafts, led to the elimination of the disease by 1951.33

Today, Europe is free from endemic transmissions of malaria but it was once prevalent in almost every country. Over the course of the 20th Century, transmissions were in rapid decline. As in the U.S., there were some outbreaks that rocked the declining trend on the continent such as during the First and Second World Wars. For example, in 1943 over a 6-week campaign in the eastern part of the island of Sicily, the British army had 11,000 cases of malaria and only 7,000 battle casualties34. By 1975, Europe was considered free of endemic transmissions. Agricultural practices, housing quality, urbanization, changing of land use and improved healthcare are factors that have been credited, in part, to the decline in the disease35 and after the wars, as in the U.S., the use of DDT insecticides, the wider availability of antimalarial drugs and initiatives such as the Global Malaria Eradication Programme founded by the WHO in 1948, contributed to eliminating the disease.

A report carried out in 2016 assessed the spatiotemporal drivers of malaria elimination in Europe, it found that the change in climate actually had very little correlation with the decline in malaria. The clearest correlation, from 1900 to the period of malaria decline for each country, was connected to the GDP36, life expectancy and proportion of population urbanized37.

Although malaria has been successfully eliminated in specific geographical areas, there is still a long way to go in order to eradicate the disease worldwide. It is also important to recognize that in temperate regions the reproduction rate of malaria is considerably lower than in the tropics. Moderately intensive efforts at vector control and case management can therefore lead to elimination of the disease.38

Methods of Prevention and Control

These are the main methods currently used in the prevention and control of malaria that rely upon funding and investment:

Vaccines are making a big impact in the fight against malaria. The RTS,S/AS01 (RTS,S) created by GlaxoSmithKline, is the first vaccine to significantly reduce malaria in young children. In 2019, the WHO coordinated a large-scale pilot program introducing the vaccine in key areas in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. Following the success of the pilot the vaccine has been approved for a roll out of 18 million doses to 12 African countries for 2023–202539. In October 2023, a second vaccine was approved by the WHO: the R21/Matrix-M vaccine developed by University of Oxford40.

Anti-malarial drugs such as artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the most effective antimalarial medicines available in the treatment for Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest malaria parasite. ACTs combine two active pharmaceuticals with derivatives of artemisinin extracted from the plant Artemisia annua and a partner drug. The artemisinin compound reduces the number of parasites during the first three days of treatment and the partner drug eliminates the remaining parasites41.

Vector control methods that are currently being invested in and developed, according to WHO Global Observatory on Health Research and Development (GOHRD), include: Insecticide-Treated Mosquito Nets (ITNs), Genetic manipulation of vectors for disease control (gene drive/population suppression), targeted sugar baits with an active ingredient designed to attract and kill mosquitoes, genetic engineering (self-limiting male mosquitos), modification of housing, larvicides, indoor residual wall treatments, peridomestic combined repel and lure devices, personal protection, spatial repellent, systemic insecticides and endectocides.

Education and increasing awareness in everyone from the general population to the decision makers in governments and local councils is essential in tackling the spread of transmissions and eventual elimination of the disease. This can include healthcare instructions to ensure patients take medication correctly, to help people recognize the early symptoms of the disease for a quick diagnosis; how to use nets, repellents and other tools correctly; and how to eliminate breeding grounds. It may also be to promote collaborations between neighboring villages or across different industries.

Access to mosquito control tools, education and healthcare is required to fight transmissions. Many people in poorer communities don’t have immediate access to healthcare and may not have a method of transport to get healthcare when already ill with the disease. Improvements in infrastructure, mobility and innovative ways of sending medication to hard-to-reach locations is required.

Data collection is essential to monitor and evaluate malaria control methods. Innovative technologies such as mobile applications-based technologies such as smart mobile apps and Short Message Service (SMS) have been developed to collect data and issue alerts42. For example, in India a Mobile-based Surveillance Quest using IT (MoSQuIT), is being used to streamline malaria surveillance for stakeholders, from health workers in rural India to medical officers and public health decision-makers. In Zanzibar, Coconut Surveillance is an open-source mobile software application designed to assist in malaria control and elimination. Drones are also being used to deliver aerial sprays to kill mosquito larvae, identify mosquito breeding sites using aerial imaging and to distribute drugs and vaccines43.

Tailor-made Control Methods

To successfully eradicate malaria around the world it’s essential to tackle malaria from both a small-scale, local approach as well as tackle it on a global scale. The WHO currently advises to target malaria interventions based exclusively on the risk of the disease in an area; however, to implement the most effective method in any given region a customized approach is needed to account for local circumstances. Successful intervention requires not only an understanding of the epidemiological aspects, but also on the specific socio-economic and cultural factors of the region, as well as the policies or the conditions of the local health system, defined as the ‘stratification dimensions’44.

Rick Scavetta, U.S. Army Africa Public Affairs

Malaria’s prevalence is fed by a variety of socioeconomic factors. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is one of the worst affected areas in the world. Over the last two decades studies have been carried out in the region to determine what these underlying factors may be, and how best to mitigate them. By analyzing and determining the relationship between housing structure, educational level, occupation, income and wealth, against the epidemiology of malaria/vulnerability of exposure in the region it became clear that those with a lack of education, low income, low wealth, living in poorly constructed houses, and having an occupation in farming may increase risk of Plasmodium infection.45

In 2002, two Kenyan cities were chosen to carry out interviews on a range of households to analyze their mosquito-avoidance practices. The findings were that low income individuals and households that cannot easily afford to buy chemicals such as repellents, insecticide treated bed nets, drugs or other related medical costs were the most at risk.46 Lack of education may also correlate to inefficient levels of awareness about prevention and treatment strategies.47

Outside of Sub-Saharan Africa other countries are having to approach specific regional problems to control the disease.

Case Study 1: Thailand

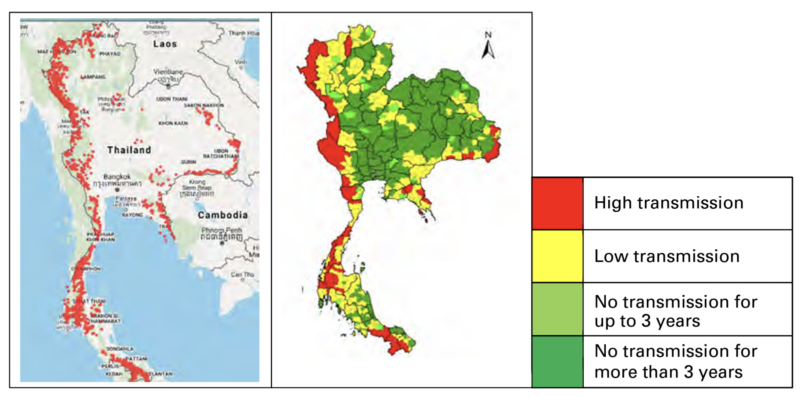

In 2019, a cost-benefit analysis was done on the case for investment in the elimination of malaria in Thailand48. After many decades of malaria control efforts in the country, significant reductions in the spread of the disease led the Thai government to create a National Malaria Elimination Strategy (NMES) to set the goal of eliminating the disease by 2024.

The Department of Disease Control (DDC) remains the main driver of malaria policy and strategy at a national level while the Bureau of Vector Borne Diseases (BVBD) manages the national database for monitoring, evaluation, and technical support, called the Malaria Information System (MIS).

Malaria transmissions in Thailand are concentrated in the forested areas near the national borders. Residents on both sides of the border frequently use the forests and trails to hunt, work (in logging), to acquire materials or to make social visits. Neighboring countries have different access to diagnosis and treatment which makes controlling the disease in these areas a challenge. Areas that had previously reduced or eliminated malaria require constant surveillance to prevent a resurgence.49 The report found that collaboration across many sectors was required, especially within the target communities, in order to succeed in eliminating malaria.

Department of Disease Control Thailand

Bajoh Subdistrict is located in Yala Province, close to the Thai-Malaysia border. In 2018, 8185 residents lived across five villages within the subdistrict. The majority of the villagers work in farming, rubber tree cultivation and management of fruit orchards. Jobs such as tapping and collecting from rubber trees require them to work at night. The climate and surrounding forest, rivers and streams make it the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes. Since 2013, this area has been one of the worst for malaria related deaths and illness. Civil unrest and conflict in the area has also exacerbated the problem.

A tailor-made model was required to tackle malaria with community-based methods of control and engagement. Addressing cultural, religious and language barriers was key in implementing strategies in the region. Many of the villagers are Muslim and speak the Malayu dialect, and so many of the healthcare workers are also Muslims and able to communicate well with the patients. Community forums were held with key figures such as village headmen, the subdistrict chief and the Muslim religious leaders (Imams). This was found to be important in order to build trust within the program.

Cultural complications had to be considered through educating the villagers once trust had been achieved. For example, some villagers, when they experienced fever, preferred to go first to traditional healers and only when the symptoms persisted and became much worse would they go to government health facilities for diagnosis and treatment.

The strategy for the region was proactive, instead of just treating and detecting cases once people showed symptoms, the principal response strategy consisted of vector control and blood screening for active case detection (ACD) and treatment. This was a way to detect and treat carriers of the disease. Constant reporting and screening, educating the local population, as well as specialist training for healthcare workers has proven a success. Due to the conflicts in the area there are also many soldiers that pass through and are stationed there. Another important step was to create a joint mission between the military and the public health sector to screen soldiers too.

Ms. Preeyaporn Suida, a Public Health Technical Officer in the Yala Province stated that there were two successes from the campaign: “First, malaria declined. But second, there was this community spirit of working together for a common community goal that was so impressive… Getting five villages to collaborate like that is not an easy thing to do.50”

Case Study 2: Colombia

The WHO’s 2022 World Malaria Report, states that within the Region of the Americas; El Salvador was certified malaria free, Belize reported zero cases for the third consecutive year and many others reported a reduction of at least 40% in cases. Countries that reported increases include Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama. Across the Region of the Americas, approximately 79% of all cases were reported in Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela51.

In Colombia in 2019, Juan Pablo Uribe, the Minister of Health and Social Protection in the country at the time, and 12 mayors from the Pacific Coast, along with representatives of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), signed the Pact for the Elimination of Malaria by 2025. At the time of signing, data showed that Colombia had seen cases of this disease decreasing and with a relatively low mortality rate. Figures from the National Institute of Health (INS), over the decade, had shown that between 60,000 and 80,000 cases of this disease had been reported annually: in 2018, there were 62,141 cases; in 2017 there were 55,117 cases; and in 2016, 84,742.52

Karen González Abril / Pan American Health Organization

The country has faced many unique political, cultural and socio-economic problems in tackling malaria. Many of these contributing factors are shared by its neighboring country – Brazil.

In 2022, around 80% of the cases in Colombia were found in the Orinoquia-Amazonia regions, on the border with Venezuela, along the Pacific coast, and Bajo Cauca and Alto San Jorge regions.

Over the past seven years, a crisis in Venezuela has resulted in more than 7 million people fleeing the country. At least 2.4 million53 Venezuelans have sought refuge in Colombia, receiving the largest number of the country’s refugees and migrants in the region. This has placed immense strain on the country’s health system. A surge in malaria has been seen on the Venezuelan border which has been in part attributed to many people sleeping outside without nets or blankets54.

One of the predominant economic activities in the region of Bajo Cauca, Alto San Jorge and the jungle regions of the western department of Chocó, is mining. Open-pit mining activities have been linked to the persistence of malaria transmission, particularly in endemic areas where access to health services and prevention programs is very limited. This is also an issue in Brazil and across the Amazonas56. Illegal mining operations in Colombia have been known to cause population displacement, deforestation and favorable mosquito breeding grounds via stagnant water pools. Some of the more rural and harder to reach locations also suffer from a lack of access to medications, vaccines and general healthcare. The latter point has been further amplified by historical conflicts in some of these areas that has made data collection and health care strategies difficult to implement.

The relatively unpredictable factors that have affected the control of the disease in Colombia and neighboring countries, reflects how essential it is to create and adapt tailor-made strategies. As with the case in Thailand, addressing malaria in just one district, country or region often isn’t enough. Bordering countries and territories must also have a program of control for the disease to be eliminated – another argument for the disease being a global issue.

Who is Currently Funding the Fight?

ForeignAssistance.gov, Global Fund, NMP reports, OECD CRS database, United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, WHO estimates and World Bank DataBank.

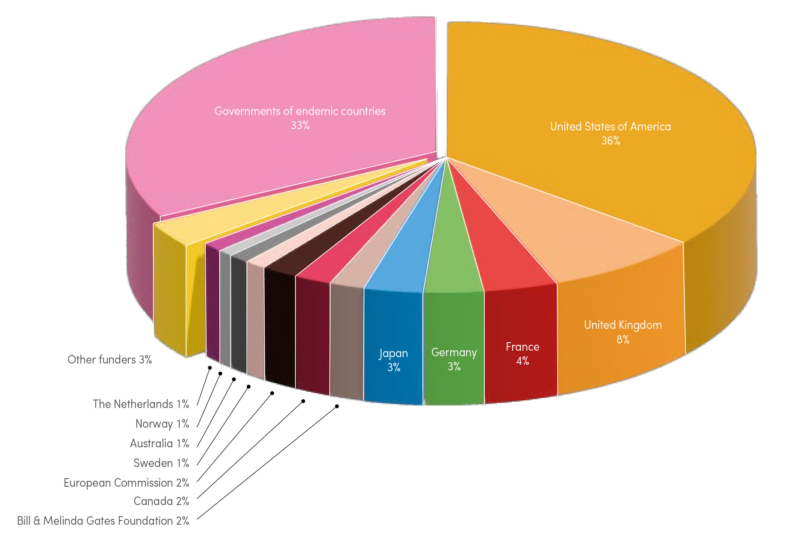

Around two thirds of malaria control and elimination funding was provided by international countries and donors during 2010–2021. The other third was provided by the governments of endemic countries. Funding for research and development comes from a range of different sectors: countries’ public sectors and private sectors including philanthropic donations, multinational corporations and small to medium enterprises. The biggest donor countries were the U.S. (36%), the UK (8%), France (4%), Germany (3%) and Japan (3%)57.

Over the last two decades the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has held malaria eradication as a top priority of the foundation. In 2021 it was the largest private donor to the World Health Organization and supplied 2% of global funding to fight malaria between 2010–2021.

The Global Fund was set up in 2002 to tackle AIDS, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria on a worldwide scale. The idea behind the partnership was to unite world leaders, communities, civil society, health workers and the private sector to find solutions to the diseases and scale-up programs of control in order to have the biggest impact with the available funds. In 2021, over 40% of the investment in malaria globally was channeled through the Global Fund58. In total it has invested more than USD 17.9 billion in malaria control programs as of June 2023.

Future Prognosis

Investment in malaria (both international and domestic) needs to increase substantially above the current annual spending, about USD 3.1 billion per year for the past five years59 according to the WHO’s 2022 World Malaria Report.

The Global Malaria Eradication Programme (GMEP), which ended in 1969, exposed valuable lessons in how to successfully eliminate malaria. While well-funded interventions can have a major impact on the disease, these gains are fragile and can easily be reversed, particularly in areas that continue to be epidemiologically and entomologically receptive and vulnerable60. These lessons have been further illustrated in the successful programs of control and elimination that have followed.

As malaria transmissions decline in certain areas, sustaining domestic and international funding can be a challenge. Mounting competition for limited resources comes from other pressing disease priorities. As seen in Colombia, reducing the transmissions of a disease, or as in wealthier countries such as the U.S. – even elimination of the disease in a particular area – doesn’t mean that a change in the region won’t see a resurgence of malaria.

It is essential to continue to monitor and adjust models of control. The changes in malaria distribution on a global scale are still an area of active research. There is still uncertainty about future malaria transmission rates worldwide, mainly because there are many factors and risks that affect the spread of the disease, including socioeconomic development, drug resistance, climate and immunity.61

According to The Global Fund, malaria control funding has plateaued, drug and insecticide resistance are increasing and climate change threatens to push malaria transmission into new regions. If there isn’t an increase in investment in fighting malaria, it must be accepted the 2030 goal to end the disease as a public health threat is being abandoned62.

Click here for references

Distribution of Anopheles vectors and potential malaria transmission stability in Europe and the Mediterranean area under future climate change, Parasites & Vectors, January 2019

https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-018-3278-6

Plasmodium falciparum in Ancient Egypt, Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, August 2008

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2600410/

Climate Change and Malaria – A Complex Relationship, UN Chronicle, United Nations, by S.D. Fernando

https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/climate-change-and-malaria-complex-relationship

Colin Carlson, a biologist at Georgetown University’s Center for Global Health Science and Security and the paper’s lead author. The study was published on Tuesday in the journal Biology Letters.

See article in New York Times

University of Oxford-developed R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine:

https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/news/181884/pioneering-malaria-vaccine-gains-regulatory-clearance/

Pioneering malaria vaccine gains regulatory clearance, European Pharmaceutical Review (EPR), April 2023

US outbreaks:

https://www.bu.edu/articles/2023/possible-malaria-outbreak-us/

Leve crecimiento de la malaria en Colombia, Federación Medica Colombiana, April 2023

https://www.federacionmedicacolombiana.com/2023/04/25/leve-crecimiento-de-la-malaria-en-colombia/

By

By