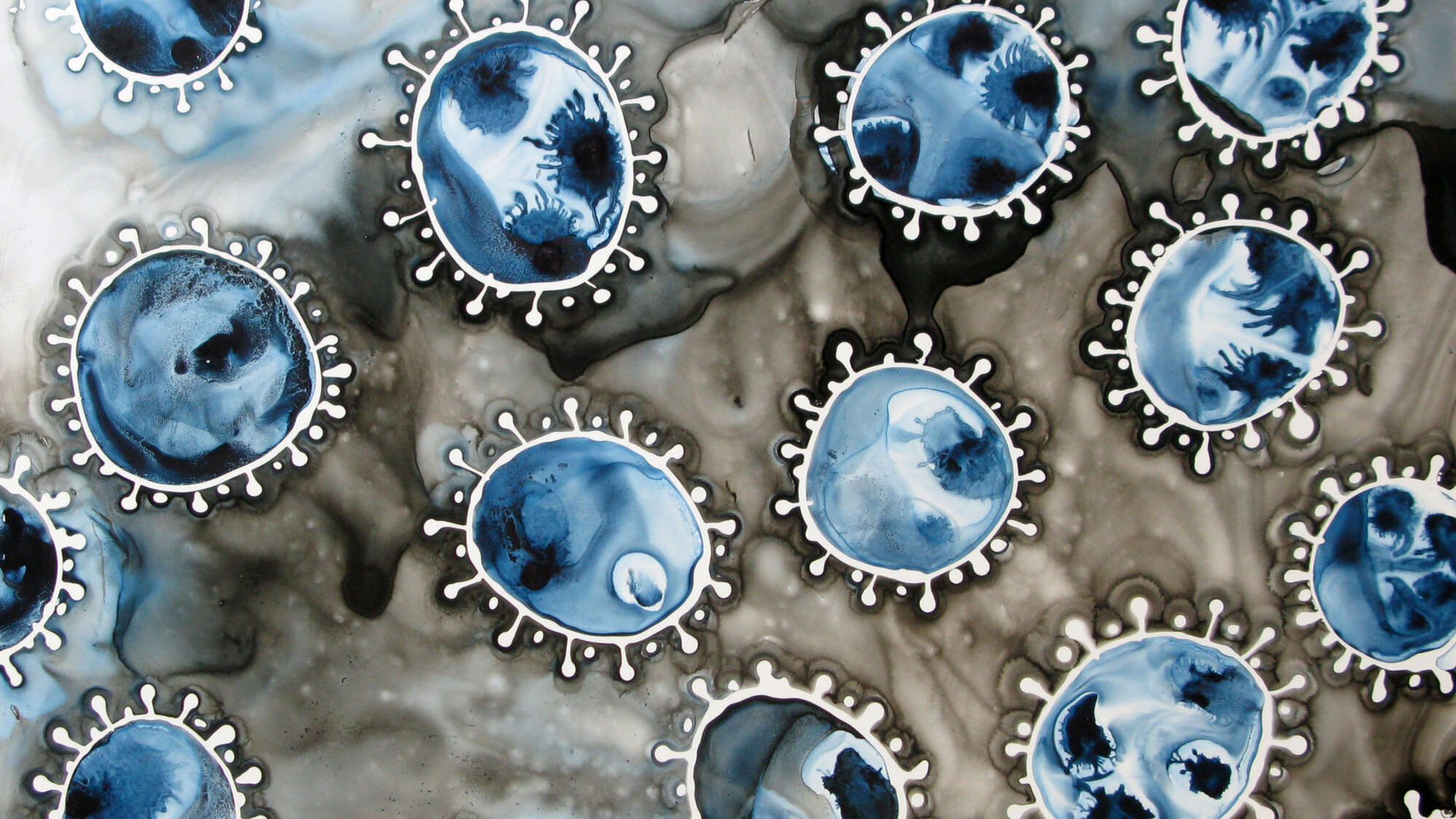

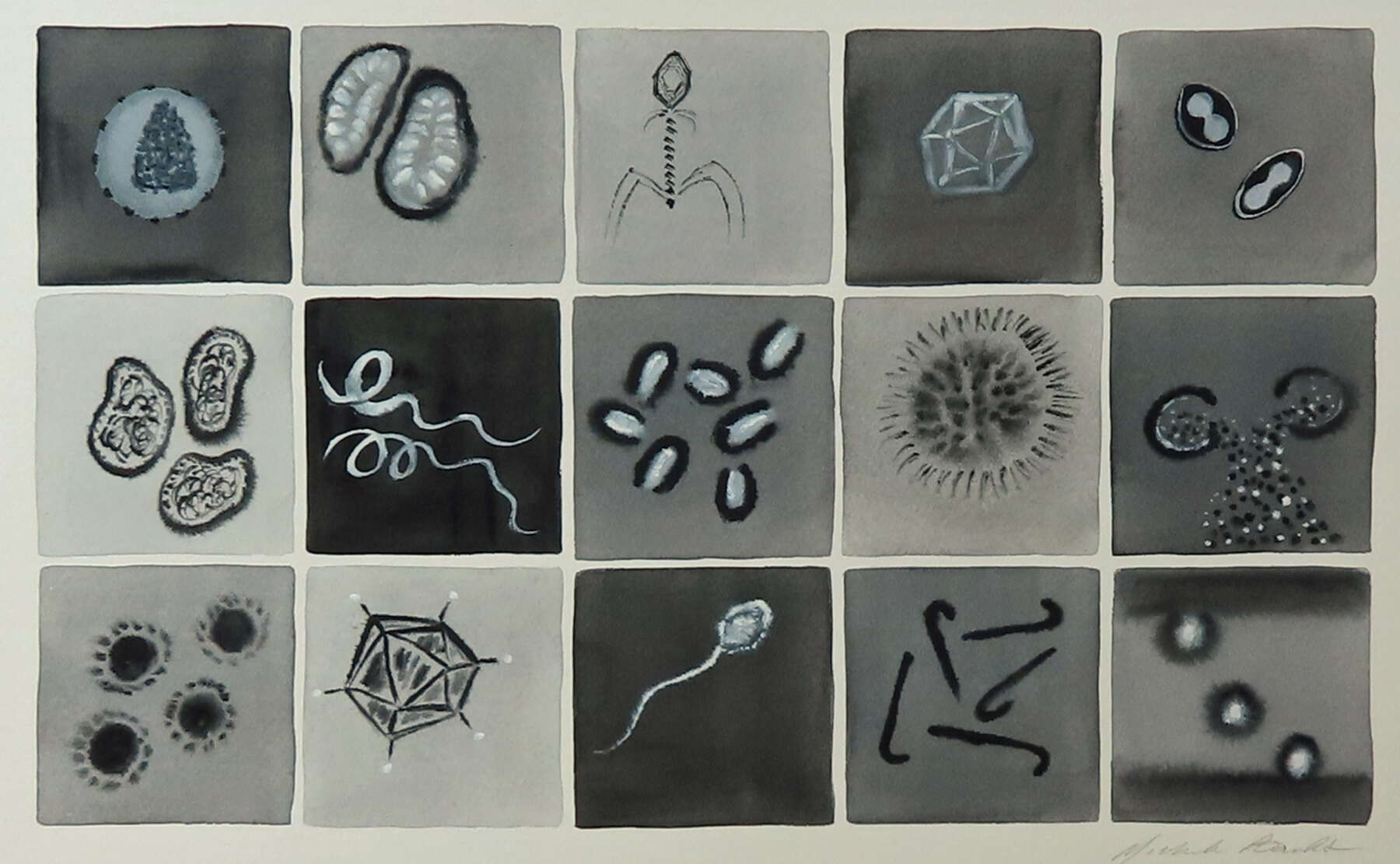

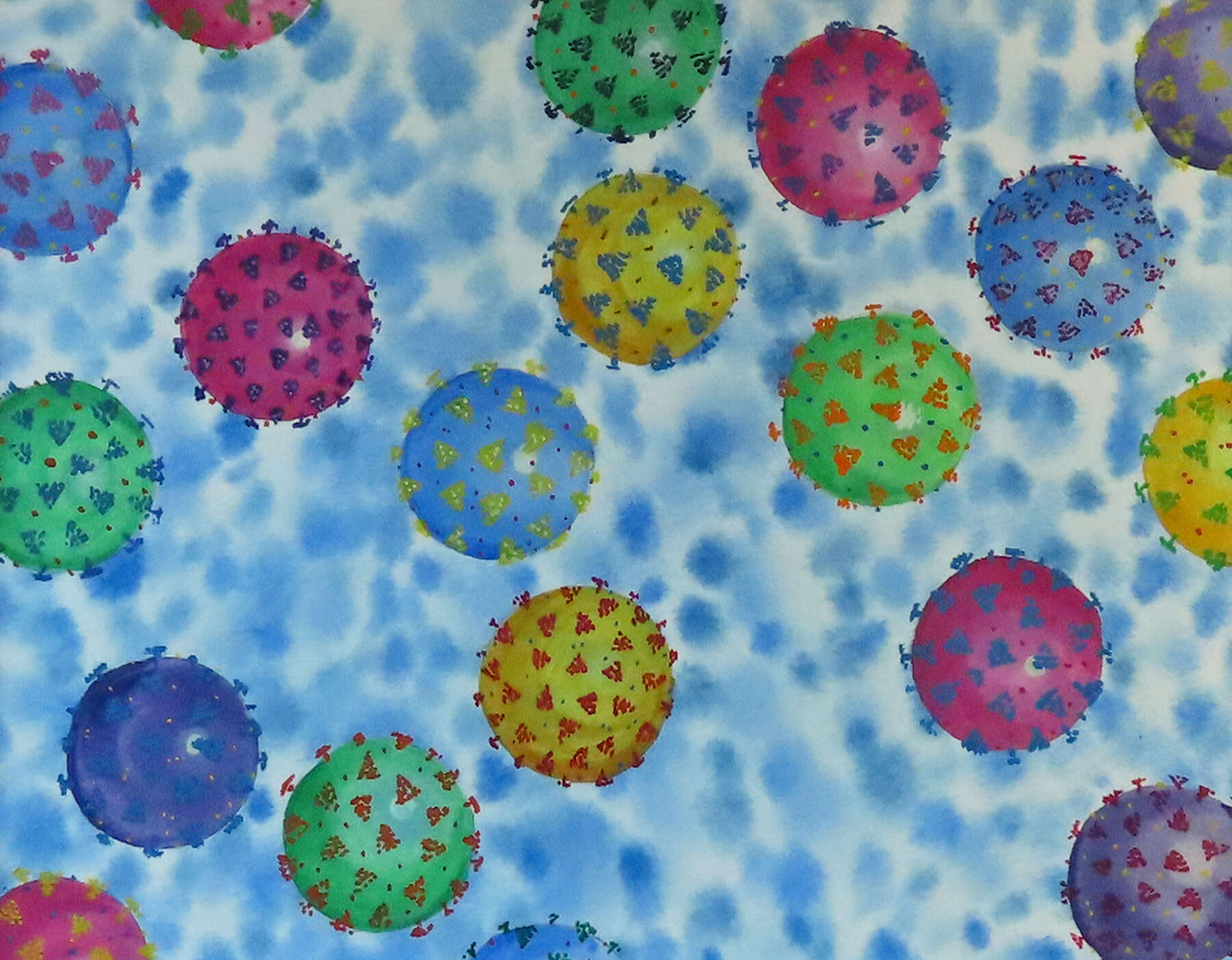

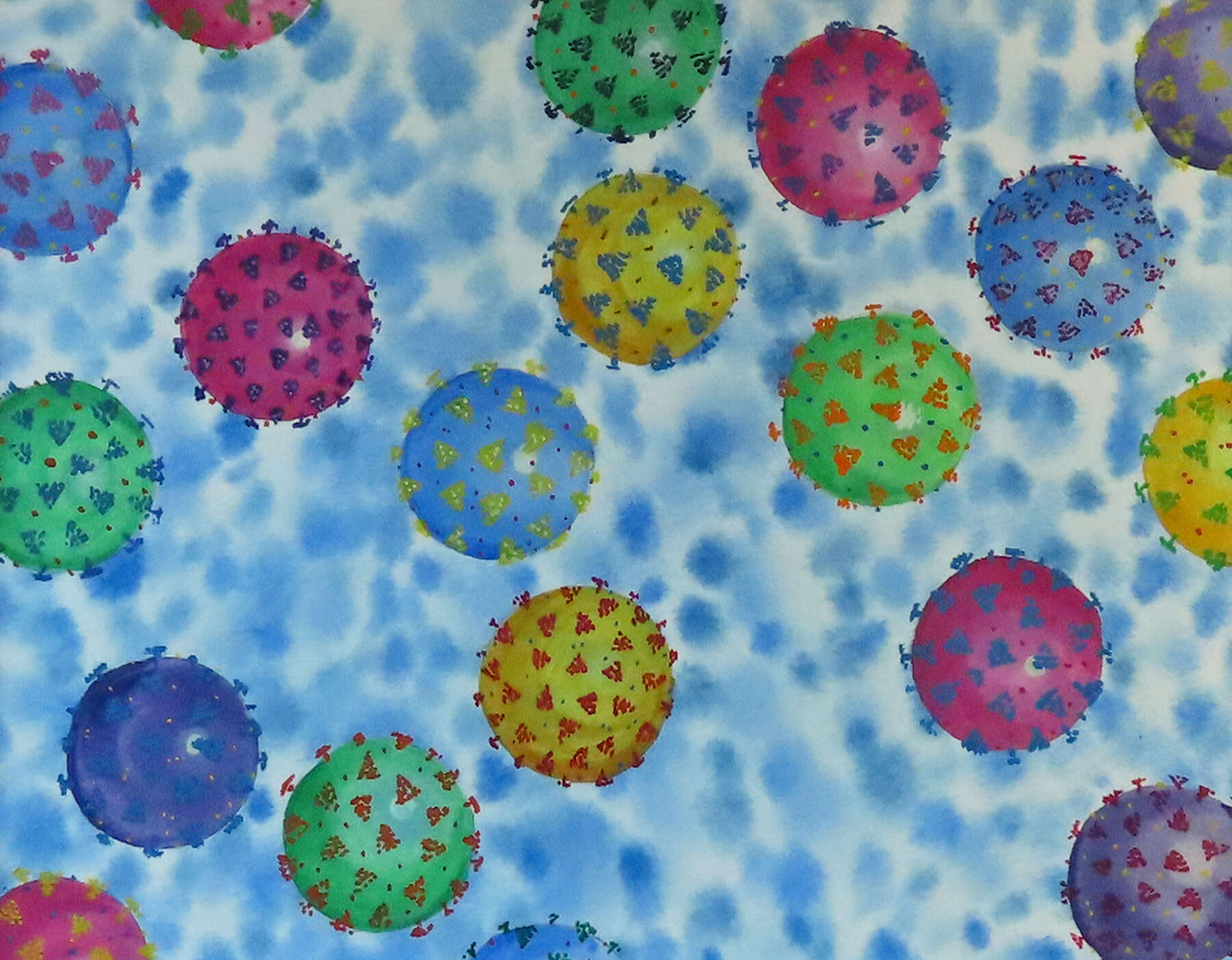

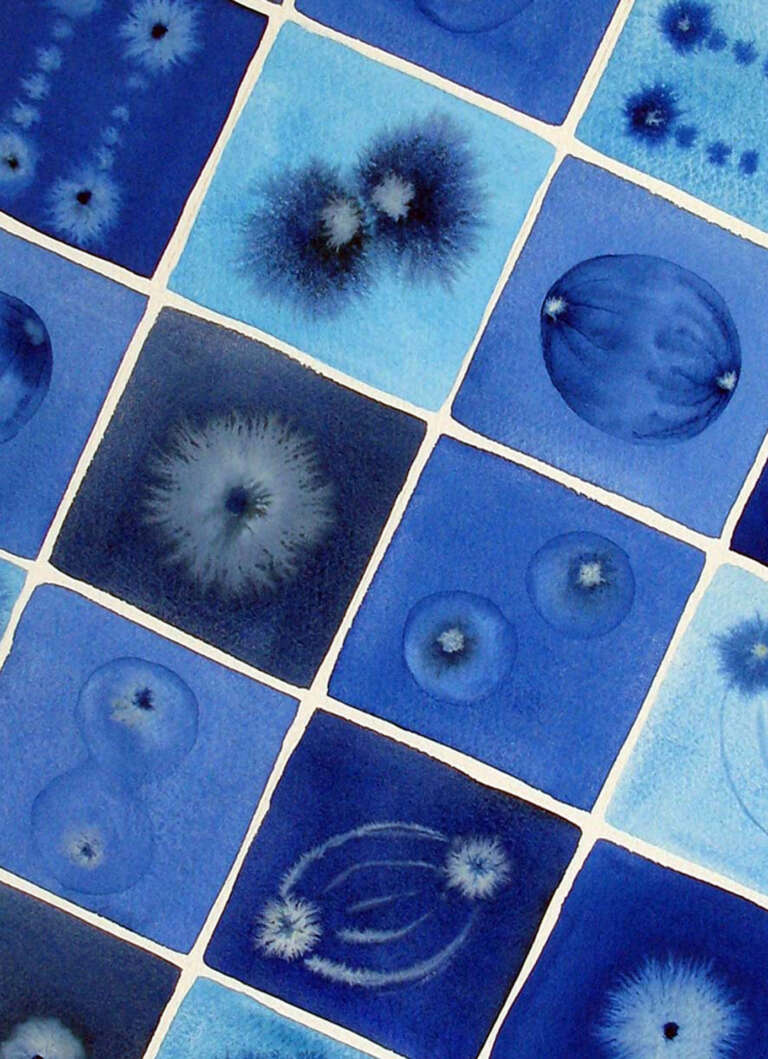

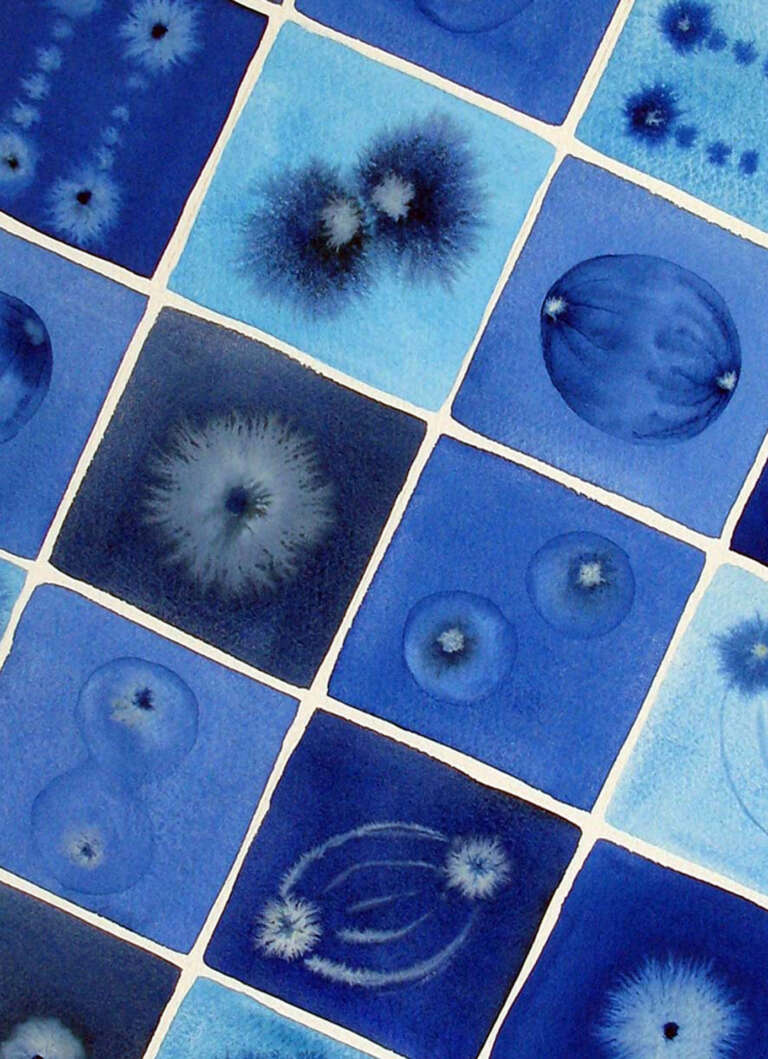

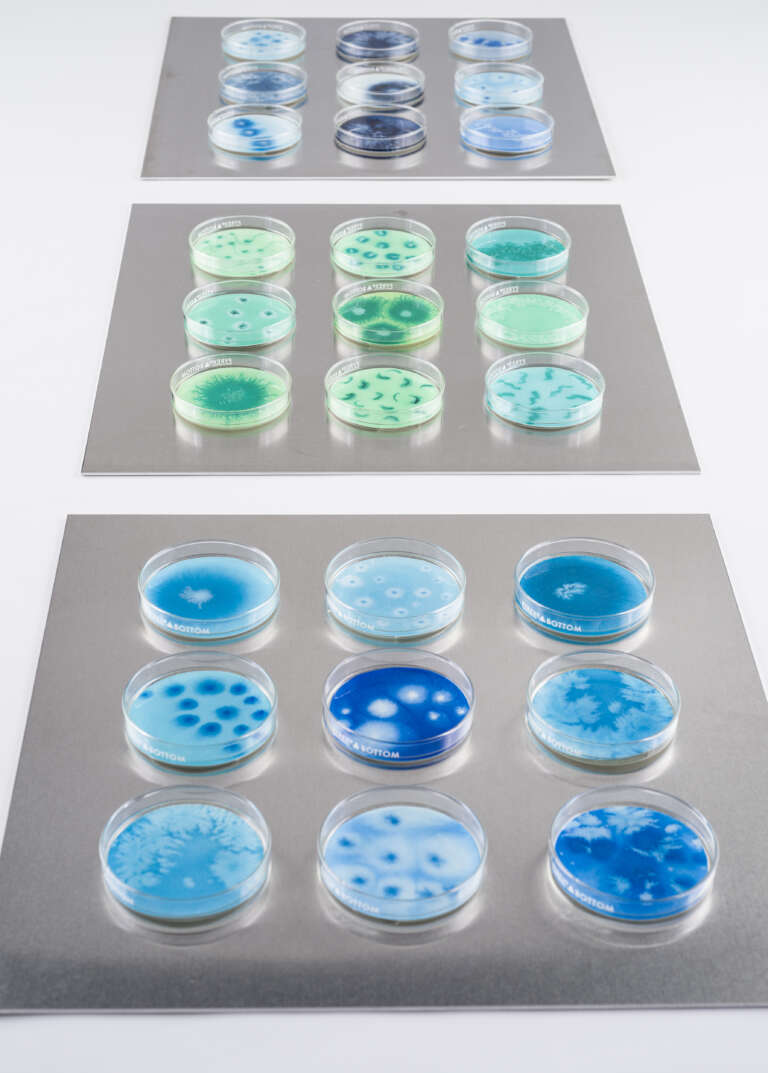

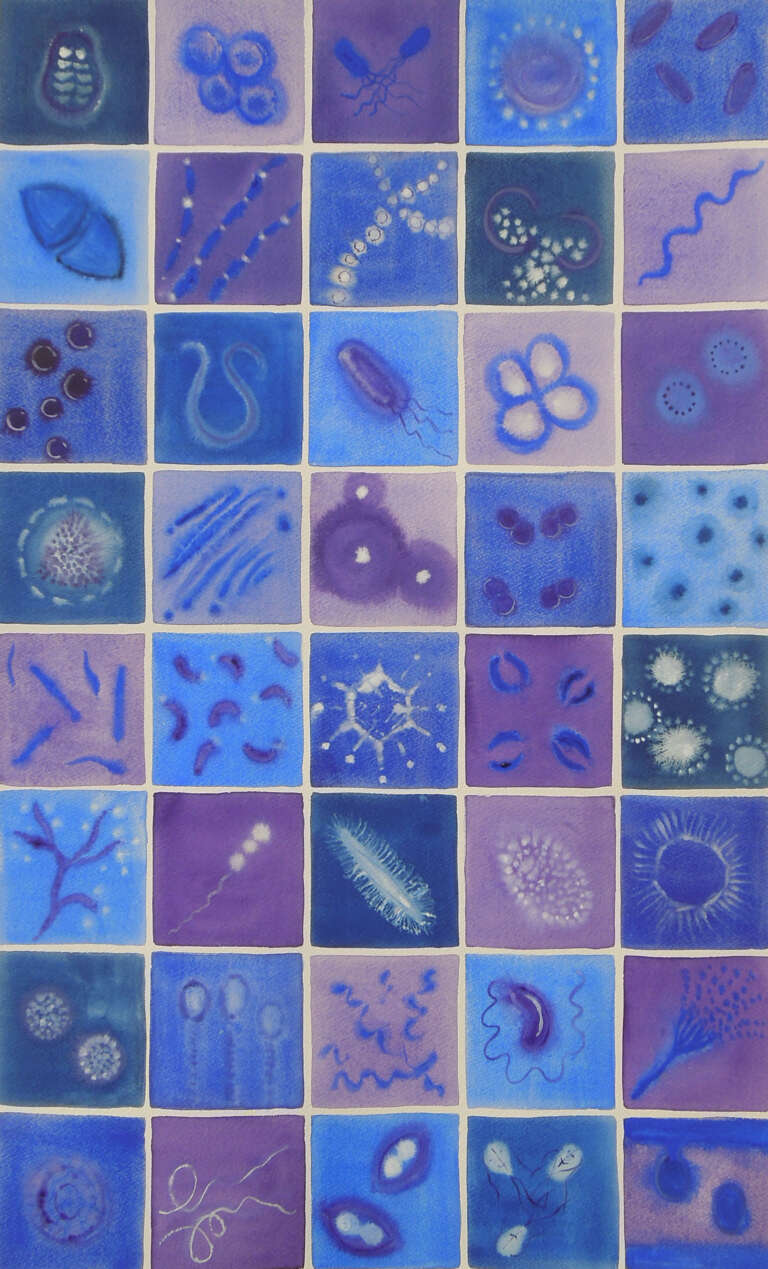

Michele Banks, known as Artologica, is a Washington, D.C.-based artist using watercolor and ink to explore themes such as cell division, neuroscience, the microbiome, and climate change. Her pieces capture a slightly abstracted scientific imagery, creating beautiful interpretations of biological and environmental processes.

Banks has exhibited her work at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), and major scientific conferences, including the Society for Neuroscience and the American Society for Microbiology. Her art has appeared on journal covers, in textbooks, and in publications such as Scientific American, The Scientist, and Wired.

She has collaborated with scientists in various residencies, including a program at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Research Station in the Finnish Arctic and a Drosophila genetics lab at the Institut Jacques Monod in Paris. Her work has been recognized with multiple grants from the D.C. Commission for the Arts and Humanities.

Banks’ work and the message she hopes to convey are best expressed in her own words in the interview below.

The Interview

Q. Can you share the story of how you became an artist?

Banks: “It’s not the usual story! Growing up, I was very much a bookworm. I didn’t think of myself as a visual person at all, and I wasn’t really an art kid at school. I got a degree in Political Science and I became a management consultant. And then at some point, I just wanted to express something in images rather than words.

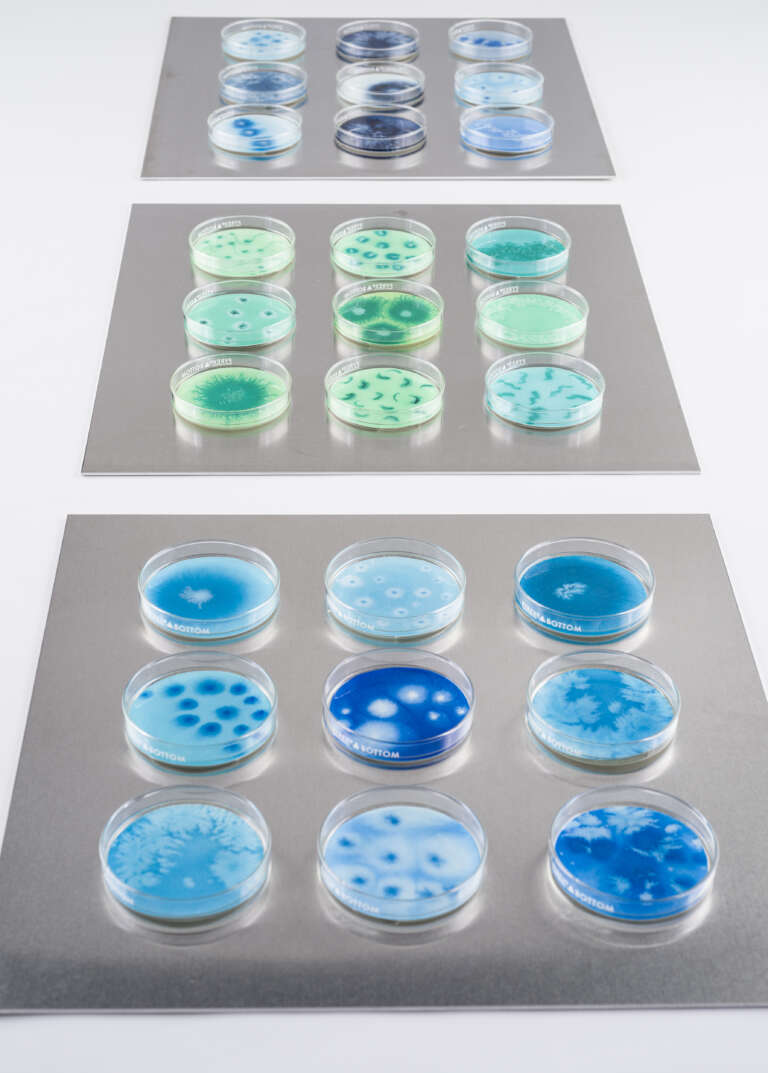

My first art projects as an adult were collages of repeated images from history texts that I cut out and pinned up in my cubicle at work. I still use these kinds of repeated images and grid patterns in my work; it must just be something that appeals to my brain. I’ve taken a few classes and workshops on various techniques, but I never went to art school. It took me many years, even long after I started selling my work, to get comfortable calling myself an artist.”

Q: Was there a particular moment or discovery that sparked your fascination with science-inspired art?

Banks: “I started experimenting with watercolors about 20 years ago. I was mainly working in pure abstraction, just playing with color and with the properties of the paint. One of the things I love to do is wet-in-wet technique, which gives a ‘bleeding’ effect. I showed some of my wet-in-wet work at the Children’s National Medical Center here in Washington, D.C., and they told me they liked my work because it looked like things under a microscope. I started looking at microscopic images and just became totally hooked. My first real artistic obsession was mitosis, versions of which I am still painting to this day. In a way, it’s the most basic biology of all. It’s life itself.

Once I started thinking about all these processes and interactions going on all the time, in our bodies, in the environment – it just took my work to a completely different place. And because scientists are discovering more and more about how microbes affect us and the world around us, there’s always a steady stream of new ideas.”

Q: How do you balance scientific accuracy with artistic expression in your work?

Banks: “I don’t try particularly hard to be scientifically accurate. I’m not illustrating a textbook, so I don’t feel like accuracy is the most important criterion for my work. I’ve had people complain that the flagella on my Vibrio cholerae were too long, and I’m like, look at a Giacometti. Nobody’s legs are that long either, but everyone understands that the sculpture represents a person. A lot of scientists I know get very upset if a double helix is twisting in the wrong direction, but to me, if you’ve recognized it as a double helix, symbolizing DNA, the visual image has done its job.

I mess with scale a lot in my work, and I simplify many images. It’s much more important to me to make a viewer think about the concepts in my work, to evoke a response, than to teach them facts.

Many of the other science-inspired artists I know feel completely differently about this. They make a great effort to be scientifically accurate, and I respect that. And again, if you’re making art that has a specifically didactic purpose, of course it must be correct. I would never recommend that anyone use my paintings as the basis for their study of microbiology!”

Q: What role do you think art plays in making complex scientific ideas more accessible or relatable to a wider audience?

Banks: “I think art can make scientific ideas more accessible in several ways. An image can provide instant clarity in a way that words cannot. Think how often we are confused by a verbal description of a concept that becomes clear as soon as we see it in a photo or an illustration. There’s a reason we say that a picture is worth a thousand words.

Another huge thing that art can do is to provoke an emotional response. When I speak to groups about the role of art in science, I often use this as an example of two images of HIV – a micrograph of the virus, and a photograph of an AIDS patient dying, surrounded by his stricken family. You could say that both are images of a virus, but one has vastly more emotional impact than the other.”

Q: Your artwork often highlights microscopic worlds, such as viruses and bacteria. What about these subjects do you find most intriguing or inspiring?

Banks: “What artist could fail to be seduced by the existence of an invisible world? It’s pretty astonishing to me that there are all these microscopic organisms, invisible to the naked eye, and that if they all went away tomorrow, life on earth would cease. The microbes are running the show in a lot of ways, which is crazy to think about, because they don’t have guns or money or any of the usual instruments we associate with great power.

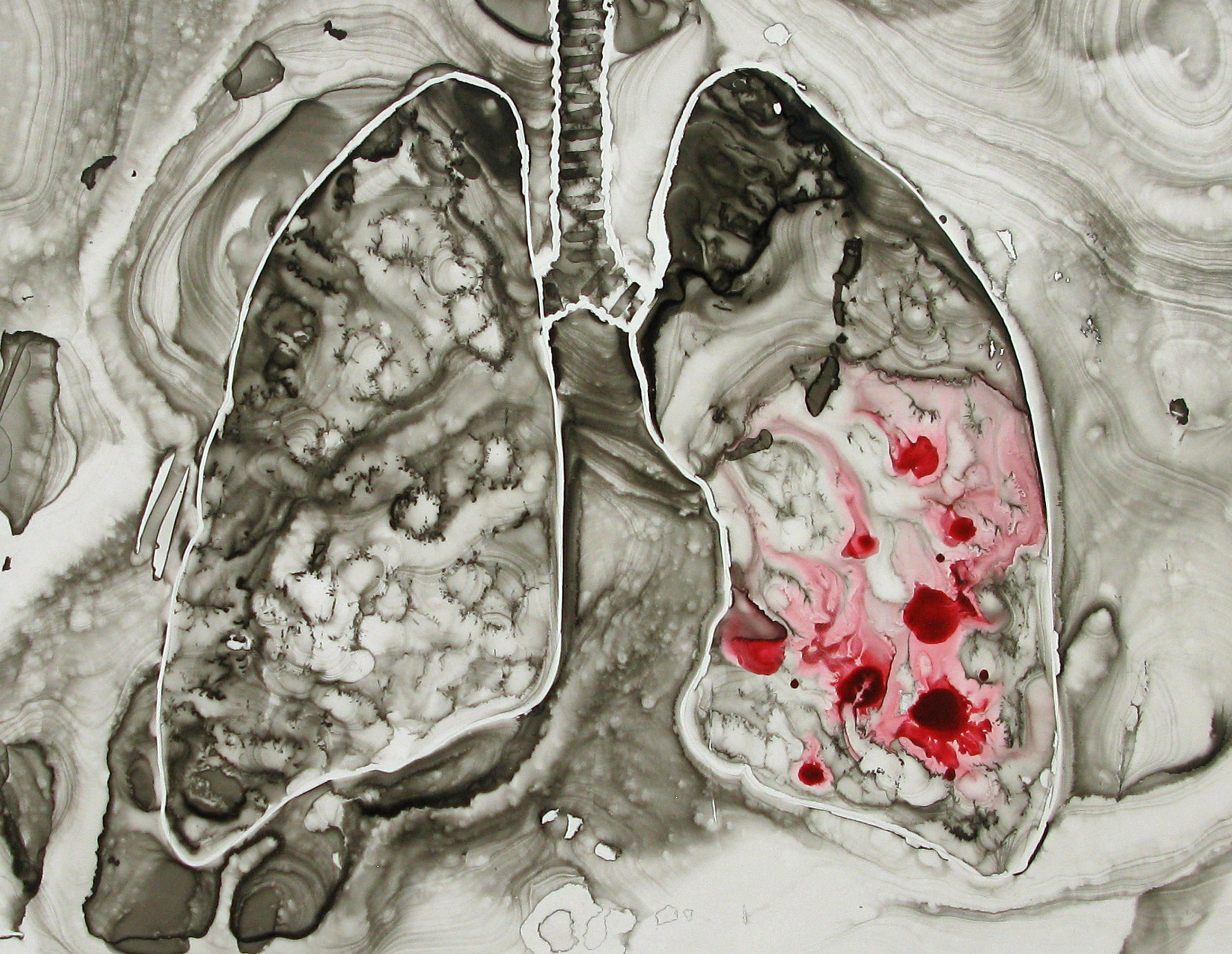

I’m also amazed by the ability of bacteria and viruses to evolve. Like a really great football team, you throw some new plays at them and they’re like, okay, we get it, here’s how we respond to that. I should add that microbial evolution is exceptionally cool when you’re making art about it and a lot less so when it’s happening in your lungs or gut.

Also, I think it’s fascinating how much scientists know about viruses but also how much is still uncertain. The issue of where viruses came from and whether they are alive, for example. Those are big questions with major implications for all kinds of things, and a lot of very smart people are still debating them.”

Q: How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence your work or perspective on depicting viruses?

Banks: “That’s a very interesting question! When COVID hit, I had been painting viruses for over a decade. During that time, many people had asked me why on earth I was painting viruses and bacteria, and then one of those tiny critters turned the world upside down. So I guess I felt vindicated about the importance of my chosen topic.

Now, one issue that comes up a lot with art that engages with science is how pretty we should make things that are causing damage. For example, beautiful art about climate change – and there’s a lot of it – can be seen as undercutting its own intentions by making people say “ooooh” instead of “oh no!” The same could be said for beautiful paintings of coronaviruses, of course. I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that this pandemic sickened and killed millions of people. It has sometimes been a struggle for me to portray, because I generally try to make my paintings beautiful. In the work I made during the early pandemic, I used a much starker palette than usual and tried more to depict some of the damage caused by the virus.”

Q: What messages or emotions do you hope viewers take away from your work?

Banks: “One thing I would like non-scientists to come away with is a sense of how fascinating scientific research is, even if they don’t grasp it on an expert level. For example, I was able to spend time in a lab that does research on evolution using fruit flies. In this lab, they do experiments using just one part of one type of fruit fly that is found on only one little island in the world, and yet their research can unlock questions about evolution, one of the biggest and most profound topics in all of human knowledge. That blows my mind.

On the other side, I would like for scientists to come away with a respect for the power of art to explore these big questions. I think if there’s one thing the COVID pandemic taught us, it’s that science alone is not enough to solve the world’s biggest problems. We need to appeal to people’s senses and emotions as well as their minds.”

Q: Are there any other scientific or medical topics you’d like to explore in future works?

Banks: “There are many! I’ve done a lot of art inspired by the brain in addition to my work on microbes, so I’m very intrigued by the gut-brain axis. There’s a lot of exciting science going on in that field which I doubt has been artistically explored. But I would need to do a lot more reading about it before I dive in.”

Q: What has been the most rewarding experience of your artistic career so far?

Banks: “Presenting my work at the Kennedy Center in 2023 as part of a program on science and art was a pretty big thrill. But I think overall the most rewarding experience was my work with Virginie Courtier’s lab at the Institut Jaques Monod in Paris in 2018. I was able to observe in her lab (and even learn to dissect Drosophila) and make some art with the scientists based on their work. Then Dr. Courtier came to Washington, D.C. and together we did a day-long workshop with artists where we had some science talks and hands-on art-making activities. A few of the artists from the workshop later collaborated on a gallery show called The Art of Evolution. So that was a really fruitful collaboration on both sides.”

Q: If you could collaborate with any other artist or scientist, past or present, who would it be and why?

Banks: “It would be really cool to work with Rich Lenski, who launched the Long Term Evolution Experiment at Michigan State. I’m such an admirer of his work on microbial evolution. The LTEE is so simple and elegant and yet so ambitious, it’s already a work of art. But I could help make it shine.”

You can learn more about Michele’s work by visiting her website: www.artologica.net.

*All images and information are © Michele Banks unless otherwise stated.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this interview are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Public Health Landscape or Valent BioSciences, LLC.