Nearly a quarter of the world’s population, or about 1.6 billion people, depend on forest resources to sustain their livelihood. This number includes an estimated 60 million who are members of indigenous groups.1 The worldviews of most indigenous peoples and cultures include a sacred obligation to serve as stewards of a healthy forest that can sustain its inhabitants for generations.

Indigenous peoples have been effectively managing their forests since “time immemorial,” yet governmental and scientific forestry experts have only recently begun to seek out the knowledge that indigenous peoples have about environmental management.

Source: State Library of Queensland (Australia) via Picryl.com

As the profession of modern forestry and the rise of governmental forest management agencies developed in various nations throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, these agencies were charged with a variety of missions. The predominant goal of the profession of forestry was primarily to manage forested land and its waters in order to regulate the industrial harvesting of lumber, palm oil, rubber, and other lucrative forest resources. For example, the field of industrial forestry developed in the United States in the early 20th century at the service of pulp and paper companies and lumber companies.

Globally, nation-states and their sub-states own substantial tracts of forest as national or provincial forests or parks, while many nations allow private, commercial ownership of other large tracts of forest land.

Desires for increased tree resources made increasingly heavy demands on forests over the past century, in addition to the increasing social need for outdoor recreation areas that accompanied the rise in tourism in government-managed forests.

As associated industries came under pressure to produce, governments developed policies to accommodate these needs. For example, in the United States, the Multiple Use–Sustained Yield Act of 1960 mandated the management of U.S. national forests under multiple-use principles with the aim of producing a sustained yield of products and services.

Forestry management practices vary widely, depending upon the ultimate purpose each forest serves to its owners or guardians. Scientific concepts and forestry practices today include techniques for sustained yield, silviculture, natural vs. artificial regeneration, agroforestry, recreation site management, wildlife management, watershed management, fire prevention/management and controlled burning, and control of insects and diseases, among others.

The contrasting philosophies between governmental agencies and traditional indigenous knowledge systems regarding how to manage the forests come into sharp relief when the forests in question have long been the lands, territories, and resources of indigenous communities.

In nation-states with a presence of internally colonized or post-colonized indigenous peoples and tribal groups, tribes today may control their forests under communal ownership authorized by treaty rights or other land regimes. With the signing of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples2 in 2007, each member state committed to grant its indigenous peoples control over developments affecting their traditionally occupied lands, territories, and resources.

However, these commitments are yet to be fully honored or operationalized in many nations. Systems for involving indigenous representation are still evolving.

The Case of the Amazon Rainforest

Of course, the most publicized conflicts over land and forest management have occurred in the rainforests of the Amazonian region, which in the mid-20th century covered up to six million square kilometers. Currently, about 47 million people live in the Amazon, including 2.2 million indigenous people in about 511 distinct groups, 66 of which live in relative isolation from the outside world.4

The Amazon rainforest is a precious resource, and not only for its indigenous residents. The rainforest’s absorption of carbon from the atmosphere is an essential element in Earth’s oxygen and carbon dioxide cycles- and its legendary biodiversity includes more than 16,000 tree species.5

However, the Science Panel for the Amazon (2021)6 reports that an estimated 18% of Amazon forests have been deforested and an additional 17% degraded in recent decades, noting that “the direct drivers of deforestation [include] the expansion of pastures and croplands, the opening of new roads, the construction of hydroelectric dams, and mineral and oil exploitation. Indirect drivers influence human actions, such as poor governance, institutional structures, policies, or commodity market conditions.”

These losses, as well as the environmental and social side effects of industrialization, threaten the long-term survival of the Amazon biome, which contains almost 10% of the Earth’s biodiversity, as well as threatening the continuation of lifestyle for the indigenous peoples and communities that live there. For these reasons, the rainforest has been a focus and rallying point for global environmental activists for several decades.

The Impetus for Indigenous Forestry

How can, and how should, traditional or indigenous forest knowledge and management techniques be influencing forestry management practices in different nations today? What are the best practices in forest management globally that include the participation of the indigenous population? Often called indigenous forestry or aboriginal forestry systems, defined as “sustainable forestry incorporating respectful interaction between aboriginal peoples and the forest,”7 these approaches incorporate not just the forests but also the industries, the people using the forest, and the institutions that govern them.

The last decades have seen increasing interest in the application of indigenous ways of knowing or indigenous/traditional knowledge systems to forest management and conservation practices based upon each culture’s worldview, its spiritual ecology, and its environmental ethical system.

The World Wildlife Fund remarked in 2022, “The infringement of the collective rights of indigenous populations seems to be a recurrent issue across the Amazon and is evident in their lack of effective participation in decision-making mechanisms related to their territorial spaces.”8

This infringement, which has occurred globally, has traditionally been marked by a decline in the protection of indigenous lands and resources, a failure to adequately oversee environmental licensing mechanisms, a lack of investment in environmental programs, and the uncurtailed expansion of logging, mining, and other exploitative industries into forests that had traditionally been under the stewardship of native peoples.

Indigenous participation in forest management practices is now mandated as an element in principles of self-determination by global governance bodies.

Hugo Asselin, an indigenous studies scholar, argues that indigenous forest knowledge is complementary to the scientific knowledge upon which Western forestry practices are built. He notes that indigenous knowledge provides essential insights based on a holistic perception of the environment as well as an intimate connection to the elements of that environment.

“Indigenous knowledge is cumulative, dynamic, long-term, holistic, local, embedded, moral and spiritual. …In other words,” Asselin writes, “indigenous people consider themselves an integral part of forest ecosystems, rather than considering they can control or manage it from the outside”.9

Asselin advocates for an ecosystem-based forest management as being the best likely meeting ground for indigenous and scientific forest knowledge. While the first stage is for governmental or private forest management agencies to learn about and begin to integrate localized forest knowledge into their practices, the ultimate goal would be what Asselin calls “full-fledged indigenous forestry.”

Ecosystems, Ethics, and Traditional Environmental Knowledge (TEK)

Ecology is a field of thinking that perceives the earth and all of its content as being in a series of interconnected relationships: humans, animals, plants, and other living organisms as well as elements of the physical environment such as air, water, and soil. Ecology is an interdisciplinary field that combines the sciences but also includes those interested in the social and cultural aspects of how humans and human communities interact with their environments.

The intersectional concept of ethics and ecosystem arose in the second half of the 20th century, popularized by the writing of forester and conservationist Aldo Leopold, who declared, “Land, then, is not merely soil; it is a fountain of energy flowing through a circuit of soils, plants, and animals”10. Leopold’s 1949 classic A Sand Country Almanac laid out the imperative for a “land ethic”:

“All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise; that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts. His instincts prompt him to compete for his place in the community, but his ethics prompt him also to co-operate (perhaps in order that there may be a place to compete for).

The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land….

In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it.”

Philosophers and cultural geographers like the prolific Yi-Fu Tuan, for example, have explored the emotional and spiritual connections between people and their physical environments as well as issues of environmental ethics.

The past few decades have seen an increased interest in the ways that non-Western peoples have traditionally perceived the concept of humans’ roles within (and relationships with) their particular ecosystems and natural environments. In the late 1990s, philosopher J. Baird Callicott11 advocated embracing the environmental lessons found embedded in non-Western worldviews, from indigenous oral traditions to the sacred texts of Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, Confucianism, and other religions.

In the Preface to his 1999 book Sacred Ecology12, resource management scholar Fikret Berkes declared, “We are moving in the new millennium toward different ways of seeing, perceiving, and doing, with a broader knowledge base than that allowed by modernist Western science”. Influenced by thinkers like Leopold, landscape architect Ian McHarg (“On Values” in Design With Nature, 1969)13, and the interdisciplinary anthropologist and social scientist Gregory Bateson (Steps to An Ecology of Mind, 1972), Berkes lamented that conventional Western scientific ecology did not consider traditional or indigenous perspectives. Instead, he pointed out that we could derive much wisdom about ecological systems not only through rational science or mathematics but also from understanding that such wisdom could “be danced or told as myth”.

About the same time, anthropologists (like those featured in Virginia D. Nazarea’s 1999 collection Ethnoecology: Situated Knowledge/Located Lives14) were studying the cultural and ecological contexts of the conservation of natural resources in terms of the “different latitudes and points of view on the local capacity for self-determination, on the nurturance of diversity, and … on creative choices balancing persistence and change”. Nazarea dedicated the volume to anthropologist Harold Conklin, who introduced the “ethnoecological approach” as early as the 1950s as he and others in his field began advocating researchers to seek out the “native point of view,” also known as “local knowledge,” rather than imposing their own observational interpretations as they attempted to understand various non- dominant cultures. As the intellectual paradigm shifted in the 1980s and 1990s, “ethno-“approaches became increasingly significant for anthropologists, who often worked with indigenous communities to document their indigenous local scientific knowledge about animal, plant, and physical resources.

Eugene Hunn15 championed the study and application of “traditional environmental knowledge” (TEK), also called indigenous knowledge or “local environmental knowledge.” He viewed TEK as providing alternative and complementary scientific knowledge to supplement that discovered by Western science. “No longer can we take refuge behind the myth of the superiority of Western civilization as the source of all science,” he declared, and said: “Furthermore, the evidence of TEK exposes the flawed logic of those who argue that science can or should be value free. For TEK is inextricably embedded in systems of moral value and integrated with the global meanings we call “religion.”

Characterizing TEK as “validated by its relevance to the daily struggle to wrest a livelihood from one’s land,” Hunn described traditional ecological knowledge as:

- both local and fragile

- specific to its immediate environment

- acquired via direct personal experience

- transmitted orally within a community

- grounded in “lifetimes of intimate daily observation”

- rooted in traditions but always adapting to technological, economic, political, and social change

Even though TEK is culture-specific to the community that sustains it, Hunn noted, it’s also relevant to world cultures as it can become a part of a comprehensive repertoire of knowledge and methods. He contrasted TEK to Western scientific knowledge, which strives to be universal and globally relevant and views the world as governed by “impersonal, mechanistic forces” rather than being infused with and animated by spirit forces.

While Hunn acknowledged the superior value of the information or data that TEK is able to provide about the local environment, he argued that its value is about more than just the knowledge alone. Traditional knowledge is not static—as Berkes noted, it gets modified with exposure to and incorporation of global opportunities and local economic needs. Berkes emphasized the notion of traditional knowledge as processual and dialogic, not just a collection of data. He advocated the co-production of knowledge between scientists and local or indigenous community leaders.

The future of our species, Hunn argued, may well rest upon the preservation of traditional ecological knowledge and the diversity (and biodiversity) it represents. Like the genome of a species, he pointed out, TEK represents a blueprint for a way of life that has survived. In an era dominated by the global capitalist society, the persistence of these individual pockets of local culture and indigenous knowledge resisting assimilation are instrumental in protecting and preserving the life of the cultural group and its ecosystem as a distinct alternative to that globalized society and its culture.

Photo by Juan Carlos Huayllapuma/CIFOR

An influential part of the conceptual paradigm shift in the social sciences during the 1980s-1990s was the pivot away from mere descriptiveness toward the analysis of power differentials in intercultural relationships, especially as they are inscribed in local practices. Nazarea wrote: “Ethnoecology needs to come to terms with the situated nature of knowledge, the constraining as well as liberating effect of this locatedness, and the importance of history, power, and stake in shaping environmental perception, management, and negotiation”.

Though many indigenous communities continue to exist, they are almost always Fourth World communities encapsulated within dominant nation-states, invariably poor by the standards of a market economy. Perceived as marginal or “backwards” by the dominant development paradigm, indigenous cultural groups occupy land coveted by the dominant economy for its natural resources. As such, the balance of power leaves the indigenous environments continually under threat.

The new millennium brought an imperative for anthropologists and other scholars to transition from cognition to action, to an engaged research methodology that has increasingly put academics in the trenches alongside activists as advocates for the indigenous communities they study.

What is Indigenous Forest Knowledge?

The concept of indigenous forest knowledge, based upon TEK but applied specifically to forest-related ecosystems and the indigenous cultures that are intimately connected to those forests, is the central concept in Hugo Asselin’s 2015 article of the same name16. He advocated that a paradigm shift in forestry practices is necessary “to base forest planning and management on aboriginal values, practices and knowledge.”

Asselin defined indigenous forest knowledge as being:

- the totality of empirical observations accumulated across many generations

- dynamic and adaptive (not static, ancient, or outdated)

- rooted in traditions and usually transmitted orally

- holistic in seeing all aspects of the environment as interconnected and mutually influential or interdependent

- local, with intimate knowledge and experience able to provide a far more nuanced and detailed description of the micro-environment than Western science can do

- culturally and environmentally context-dependent, so it cannot be readily transferred from one context to another or from one community to another

- moral and spiritual, not mechanistic or rational like scientific knowledge

The meaning of a particular forest is radically different for the indigenous people whose lives have been materially and spiritually entwined with the environment for millennia than for relative newcomers who see the forest as a collection of elements to be exploited, developed, admired, or lived in. Few First-World people possess the deep respect and veneration for the life of the forest environment—and if so, they are generally isolated individuals rather than an enduring cultural group.

Pikangikum First Nation elders in Northwestern Ontario, Canada, just as with most indigenous peoples, amass a wealth of forest knowledge passed down through the generations and then accrue knowledge throughout their lifetime of direct experience with the other beings (both plant and animal) in the forest. In their worldview, they perceive that even after a living being dies or is killed, a residue of self or subjectivity as complex as that of human remains, even if it is not accessible to the Pikangikum people.

In their forestry plan for the Whitefeather Forest Initiative17, the Pikangikum elders explicitly clarify that their cultural concept of “forest” is different from what outsiders may see or think of. “We have a special understanding of the word ‘forest’ (noopeemahkahmik)…. [The term] does not simply refer to an area with trees (nohpeemeeng), but speaks of our special place deep in the heart of the forest; a spiritual relationship with the Creator which has invested in us a special responsibility to ensure Creation is respected and cared for.”

One problem with government policies of forest protection and biodiversity conservation strategies, Asselin argues, is the long-term history of human interaction with the forests. “Considering themselves as integral parts of the ecosystems, indigenous people cannot contemplate ‘putting a dome’ over an area and preventing themselves from using it,” he writes.

On the other hand, locally defined policies that may prohibit commercial hunting or logging by outsiders but allow use of the forests for harvesting medicinal plants, subsistence hunting, or gathering firewood, enable indigenous communities to retain their traditional relationships with the forests. Indigenous people, usually present year-round, are better able than state foresters’ seasonal projects to monitor the environment and note any changes occurring.

Source: Juan Carlos Huayllapuma/CIFOR

In fact, even the principles and criteria of what defines “sustainable forest management” need to be locally and culturally specific. Managers need to also consider that a forest’s products and resources are not only trees but also all the other plant species, including edible and medicinal plants, as well as animals that inhabit the forests and their rivers and streams.

Although each indigenous group has its own distinctive culture, some of the more common values and environmental ethics found across indigenous cultures include an abiding respect for all living animals and plants in their ecosystem and an understanding that one should only take and use what is needed, without waste.

Participants and stakeholders in forest management collaborations involving the cultural knowledge of indigenous groups take into account the wisdom of the community elders as they find ways to integrate local, traditional forest knowledge and practices with those of modern forestry.

This includes a sensitivity to many intercultural variables. For example, an intercultural issue that may arise could be about mapping and the representation of space on maps. In the situation regarding the Tinto Community Forest in Manyu, South Cameroon (see more below), paper maps, as opposed to digital maps, were more accessible to the local indigenous participants. The size of the maps mattered, too, since the Tinto community members preferred larger maps and argued that culturally significant sites for those with intimate local knowledge, like caves and other cultural landmarks, should be mapped as well. However, in other cases to the contrary, indigenous groups may be hesitant to share their culturally sensitive information, such as precise sacred sites, with outsiders.

Along with the mission of coming to understand a particular body of indigenous forest knowledge as a cultural outsider, the processes of making and operationalizing environmental policies are themselves fraught with contested understandings about knowledge, truths, and values. Integrating indigenous and non-indigenous knowledges, which may be quite different in terms of ways of seeing the world, is never a simple task. Many efforts are bound to fail if entered into without adequate time, mutual respect, and attention to nuanced cultural differences in approaches.

Tribal forest management results in larger, more mature trees, higher tree volume, more tree regeneration, fewer invasive species, and a greater diversity of native plants beneath tree canopies, according to a 2018 study in the United States by Donald Waller and Nicholas Reo comparing ecological outcomes for tribal (Ojibwe and Menominee), public, and private forests.18

Waller and Reo found that public and privately managed forestlands lost significant plant diversity throughout the past century and have not been able to regenerate tree species that are sensitive to deer herbivory. The resulting shifts in forest species composition and wildlife populations put at risk the ability to sustain wildlife. The researchers recommended that lessons from tribal forestlands could help improve the sustainable management of nontribal public forestlands.

The Anicinapek First Nation of Kitcisakik (Canada)

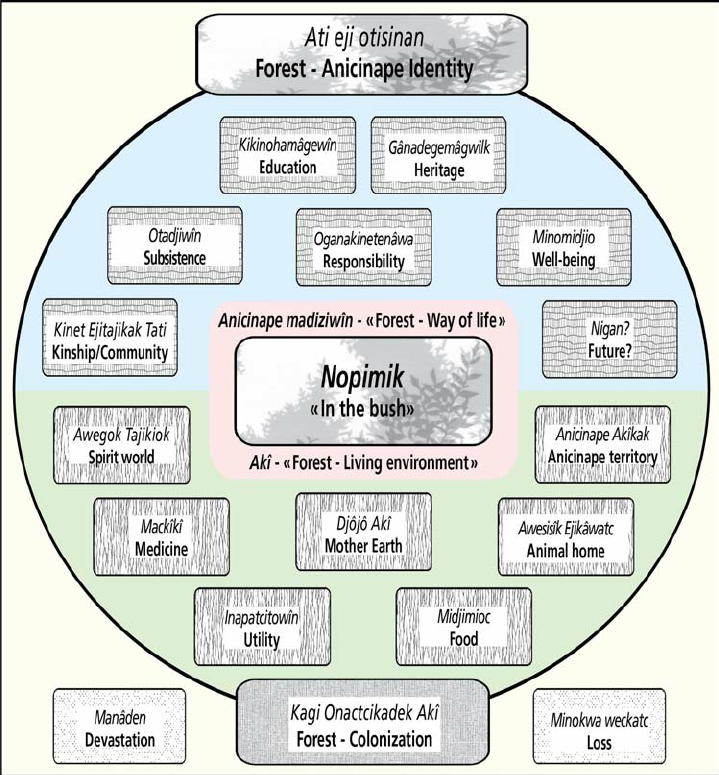

To illustrate the complex and multifaceted meaning of a forest for an indigenous community, the chart below provides an example of how many aspects of a culture’s life can be mapped onto its forest environment. This diagram visualizes the meaning and identity of the forest for the Anicinapek of Kitcisakik, a First Nation in Quebec studied by indigenous forestry scholar Marie Saint-Arnaud and colleagues.19

Source: Saint-Arnaud et al. 2009

The ancestral lands of the traditionally semi-nomadic Anicinapek are located mostly within the boundaries of the 6000-km² Réserve Faunique La Vérendrye, a wildlife reserve managed by the government agency Sépaq. These lands are in a mixed balsam fir, yellow birch, and white birch bioclimatic domain. In the past century, colonization and industrial forestry have had a dramatic effect on land use as well as on the Kitcisakik community’s social organization, leading to tensions and conflict.

Since 1970, more than 60% of the productive ancestral forest area has been deforested, with between 300,000 and 400,000 m3 of timber annually harvested by outside forestry companies.

In 2001, following a crisis between the First Nation, the forestry industry, and the government, Kitcisakik Band leader Jimmy Papatie (one of the article’s co-authors) initiated a dialogue: “I saw at the time that the community did not understand forestry language. We did not have the tools to comprehend what was happening. I suggested setting up a local committee to take care of the forest”.

Under Papatie’s leadership, the Kitcisakik Band Council reached out to create “a community-university-industry-government partnership” charged with defining the foundations for an indigenous forestry initiative. It began with a four-year qualitative study of community members’ representations of the forest and its meanings, as illustrated by the chart above. The research also revealed the community’s perceptions of outside forestry approaches.

The significance of this ethnographic Anicinape approach is that it was rooted in the values, attitudes, concerns, and knowledge of the community. The comprehensive results consisted of culture-specific criteria and principles. The collaborative team fostered the creation of a local framework of five principles (cultural, ethical, ecological, educational, and economic) and 22 criteria for sustainable forest management.

How Can Indigenous Knowledge Contribute to Forest Management?

In addition to the Anicinape, the following case studies illustrate just a few of the dozens of situations through which partnerships between indigenous cultural groups and government forestry management agencies have been established. Some have worked better than others, but lessons have come from each.

The Menominee Tribe (United States)

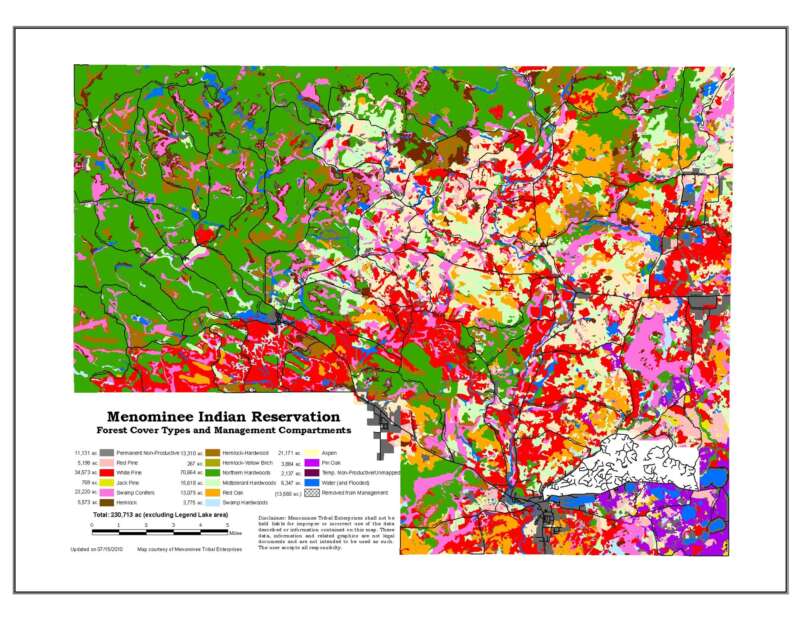

The Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin in the United States provides a classic example of how indigenous knowledge can influence forest management. The 235,000-acre Menominee tribal forest is the largest tract of virgin, native timberland in the northern Midwest and Great Lakes region. About two dozen hardwood and softwood species of trees—including red oak, aspen, pine, hemlock, and maple—cover nine-tenths of the land, overseen by Menominee Tribal Enterprises.21

A few decades after the tribe’s reservation was created in an 1854 treaty, the U.S. Department of Indian Affairs encouraged the tribe to clear the forest and create farmland. Congress passed an act in 1890 authorizing the tribe to harvest and sell timber from the Menominee forest. However, tribal leaders considered their forest to be a collective resource that, if managed well, might enable the tribe’s members to maintain their cultural livelihood on their land, which provided animals and vegetation for sustenance.

As indigenous forestry specialist Michael J. Dockry has written, “Menominee people did not intend to trade the forest and their forest-based culture to become industrious farmers. In contrast, they used the 1890 law to provide tribal employment and increase tribal and individual revenue while maintaining the forest and controlling it to the extent they were able. … Despite the intentions of lawmakers, the Menominee tribe used the political and legal systems to achieve their own vision of forest management, maintain their forest, and increase their control over the land”.22

According to tradition, Chief Oshkosh (1795-1858), who led the tribe through all the traumas of the mid-19th century including forced sale of 7 million acres to the U.S. government in 1848, resisting federal relocation to Minnesota, and resettling on the current Wolf River reservation, determined the tribe’s forestry strategy: “Start in the west, make your circle by taking only the sick and mature trees, yet, keep in mind by taking care of the other creatures and leaving it as you first came, as so when you make your circle to the point of the start, you then will again have another stand ready for you on your next circle. For it is truly this circle, if we take care of her, Mother Earth, for it is true that she will always be there to take care of you!”23

In the early 1800’s, non-indigenous commercial logging companies, called the Pine Ring, coveted the tribe’s woodlands, and began illegally harvesting timber. However, between 1872 and 1890, the tribe fought for the legal right to harvest its own timber and began its own logging operations under government supervision.

Source: Menominee Tribal Enterprises

For more than 150 years, the tribe has served as stewards in managing its forest and its logging operations using sustained yield techniques, the goals of which, according to the Menominee Tribal Enterprises, are to “provide for maximum diversity in the forest (species composition, age class distribution, structural diversity both within and between stands), habitat diversity, and to optimize growth and saw log quality of the forest timber resource.”24

Today, adding modern technology like drones and computer imaging to their toolkit, the indigenous Menominee forest management is acclaimed for having the healthiest managed forest in the United States utilizing hand-culling techniques that rank forest health ahead of profits—but that still bring in a hearty income for the tribe.

However, the industry is currently facing a decline in production, according to a recent New York Times report, due to a labor shortage, the aging workforce and machinery, and a demand that exceeds supply.27 As the tribe continually keeps its eye on its people’s future, it’s using its tribal college to develop a younger workforce, considering upgrades to automation, and applying for grants for new sawmill machinery.

The Pikangikum (Ojibway) First Nation of Canada

Just as the Menominee Tribe has maintained its own code of environmental ethics while collaborating with the professional forestry industry, other indigenous groups are doing the same. The Pikangikum First Nation lives in a remote access community in the Whitefeather Forest of Northwestern Ontario that is only accessible by air or boat.

One of the community’s enterprises is the Whitefeather Forest Community Resource Management Authority, a First Nation-owned corporation mandated to manage and develop the forest. The tribal community is planning to build an Indigenous Knowledge Teaching Centre within the forest “where our children and others, including First Nations and non-aboriginal students from other communities, will be able to learn about our land directly from our Elders.”28

This Ojibway community has cultivated a worldview with a concept of stewardship as a set of moral principles and behavioral norms. Tribal elders teach these lessons through oral storytelling and demonstrate them in practice through their activities of daily livelihood.

Spiritually and pragmatically, instead of perceiving the non-human beings in their biosphere as less important objects to be controlled, manipulated, or managed, the Pikangikum view them as equals: as “decision-making agents with their own relationship to the Creator”.30

This affects not only the tribal members’ practices but also the language they use to discuss their involvement with the natural environment: rather than using “tools” to “manage” the forest, they conceptualize themselves in a mutual respect-filled working relationship with each of its elements.

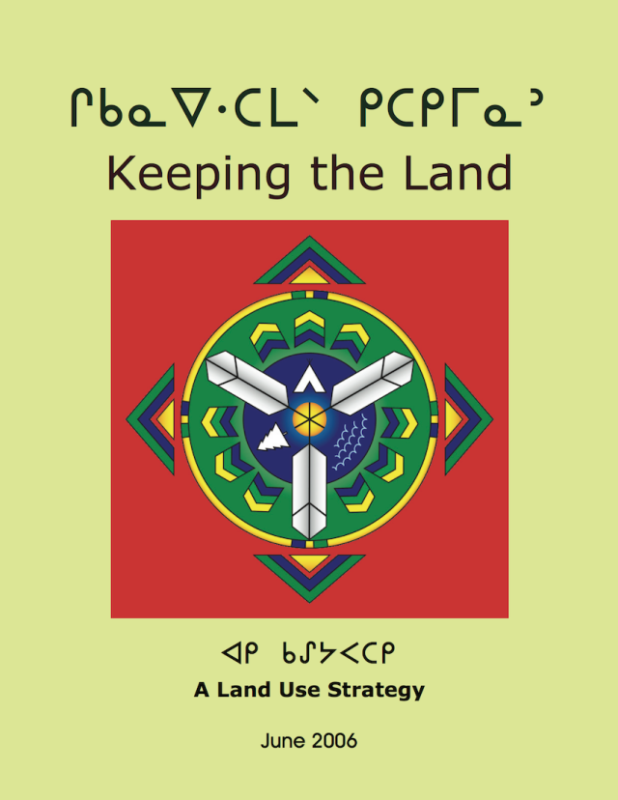

Using community-based research to create the community’s Indigenous Knowledge data set, the Pikangikum Elders developed a land use strategy called “Keeping the Land” in consensus with Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources.32 Its preface contains a vision statement, excerpted here:

“Through our customary Indigenous Knowledge and land stewardship traditions (Ahneeshsheenahbay kahnahwaycheekahwin), passed down the generations through teachings and practices learned first-hand on the land, Pikangikum people have maintained our Aboriginal relationship to the lands and waters that make up our Ahneesheenahbay ohtahkeem (ancestral lands). Our vision expresses our intention to maintain this Ahneesheenahbay relationship to the land, to maintain our Ahneesheenahbay way of life, in conjunction with and through the new land use activities proposed in this Land Use Strategy. These new activities will be integrated with existing land uses (kahyahtay akee weeohtahcheeeeteesohweenahn) in a way that is guided by the Pikangikum (customary stewardship approach Ahneeshsheenahbay kahnahwaycheekahwin).”

The Purepecha (Mexico)

Farther south, Mexico’s Lake Patzcuaro Basin region has faced uncontrolled historical deforestation and degradation from logging, woodcutting, forest fires, cattle ranching, and agricultural expansion, as Daniel Klooster’s 2009 case study documents.34 This area of forests held as common property has long been the home of the indigenous Purepecha people.

Despite a decrease in agriculture over the past century, the demand for wood for home cooking and for wood-based cottage industries like pottery has become much greater than the authorized wood allocation and the rate of forest growth. Between 1963 and 1990, the forested area decreased by as much as 50%, with some areas completely denuded of forests.

Researchers studied the local forest knowledge and practices of two villages, Santa Fé de la Laguna and San Jerónimo Purenchécuaro, which have maintained significant areas of forest cover as well as their local languages, cultures, local knowledge of forest resources, and local woodcutting practices. Of their combined 8000-hectare territories, about 40% is still forested in pine and oak.

Source: CEMDA (Centro Mexicano de Derecho Ambiental)

Beginning in the 1930s, the forests and croplands of the communities were subject to wood theft and land appropriation from non-indigenous (mestizo) neighbors. After recovering much of their land base in the 1980s, pottery production began to displace agriculture. Since then, although some reforestation has occurred, woodcutting has intensified, so forests are decreasing in density.

The Purepecha indigenous forest knowledge incorporates an ethics of woodcutting, which includes preferring:

- cutting of local oaks that will resprout after cutting and thus have continued vigorous growth for long periods

- gathering and cutting dry and diseased wood rather than healthy trees

- cutting mature trees instead of young ones

- banning the sale of community wood to outsiders

- ban on cutting trees in reforested areas

Purepecha’s indigenous forest knowledge also incorporates:

- Purepecha names for trees species

- the burning and construction qualities of different kinds of wood

- an intimacy with the territory that is full of Purepecha place-names that do not appear on official maps

- the forest’s history of fire, disease, and agricultural clearing

Klooster’s article advocates an adaptive management approach integrating local indigenous knowledge and scientific forestry that involves “cross-learning between scientific resource managers and woodcutters; participatory environmental monitoring to assess the results of different cutting techniques; and explicit management experiments to facilitate institutional learning at the community level.”

Noting that indigenous forest management systems sometimes face challenges in monitoring and reporting the forest’s response to woodcutting, Klooster noted that scientific forestry and forest ecology could fill that lack with monitoring and reporting techniques. Conversely, since scientific forest management often suffers from a lack of local institutions to ensure compliance with guidelines and adaptation to local customs and traditions, local indigenous management is essential.

Adaptive management requires, at minimum, these attributes, according to Klooster:

- Better communication between villagers and foresters, not only across a table but in the field. One favored technique among the Purepecha includes “transects” (walking workshops) in which local Purepecha elders lead walks with foresters and botanists through forests and fields, identifying Purepecha names and indigenous knowledge about various species.

- Participatory monitoring, territorial mapping, data gathering, and systematic experiments in institutional adaptation.

The Sami (Sweden)

Source: Nasjonalbiblioteket from Norway

One model of incorporating indigenous forest knowledge is the use of Participatory Geographic Information Systems (PGIS) to inform government decision-makers and mitigate conflicts between indigenous forest users and foresters.35 Among the reindeer-herding Sami of Sweden, Per Sandström and colleagues noted, the integration of traditional and scientific knowledge in a PGIS improved the process of spatial communication, contributed to a more inclusive planning process, and improved knowledge-sharing for land use planning between the stakeholders.

PGIS contributes to enhanced governance of local resources by, as Asselin summarizes, “improving dialogue, legitimizing and using local knowledge, redistributing access to and control over resources, and empowering local communities with new skills in geospatial analysis”.36 However, he notes, challenges in this collaborative approach to forest management still remain in terms of equity, data ownership, and information sharing.

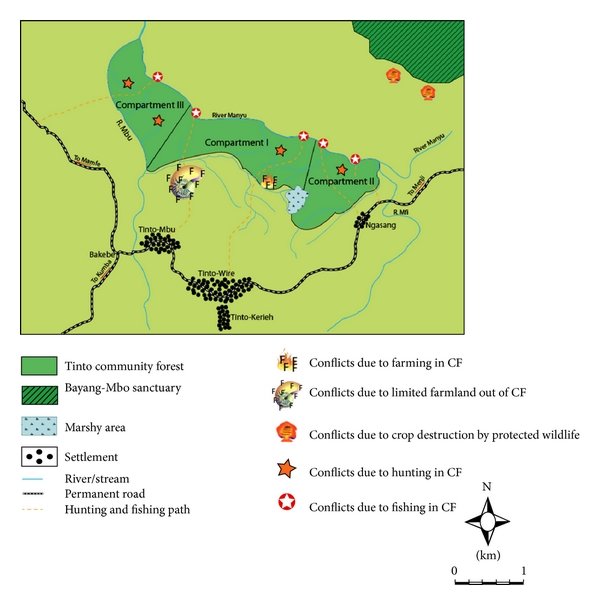

The Tinto Community Forest in Cameroon

In 1994, the Cameroon government reformed its forestry management by introducing the concept of a community forest, a joint-management concept in which local indigenous communities could undertake sustainable forest management for a renewable period of 25 years. The aim, as Researchers Michael McCall and Peter Minang explain, was “to enhance local governance through community participation, to integrate indigenous forest management practices, to provide direct economic benefits to communities, and to improve forest/biodiversity conservation”.37

McCall and Minang examined the use of participatory GIS in community forest legitimization, planning, and management in the Tinto Community Forest in Cameroon. The practice followed “Good Governance” principles, such as:

- Representation and participation of indigenous community actors

- Involvement in decision-making

- Empowerment of actors

- Ownership of spatial knowledge and process through access to geo-information and usage of GIS

- Respect for indigenous techno-spatial knowledge

- Equity in power and control relations

The researchers found that while the participatory GIS framework was a worthwhile effort, the results did not ideally fulfill the goals. “Overall,” McCall and Minang wrote, “the expected positive gains in equity did not appear. The majority of stakeholders neither gained, nor lost, much in terms of powers of control or access to forest resources”.

Most notably, the indigenous women of the Tinto community were underrepresented in decision-making, which was especially problematic since women are the main collectors of non-timber forest resources. “Although there is evidence that some effort was made to include women in the village meetings, only two women were present for the mapping of indigenous technical knowledge and indigenous spatial knowledge in the forest,” McCall and Minang wrote.

Source: S. Ngendakumana et al. (2013).

A later study by Serge Ngendakumana et al. (2013)38 found increasing dissatisfaction with the system and attributed much of the problem, including the conflicts that ensued after creation of the Tinto Community Forest, to the state’s land tenure policies. See the map.

Assessing the local attitudes about the flaws in the laws and policies regarding forest tenure and property rights, the study mapped the potential areas of conflicts between communities and the government’s forestry management as well as conflicts between neighboring communities and with outsider settlers: “Native populations think that the existing regulatory framework constitutes rather a kind of disincentive to maintain their active involvement in forest conservation especially as those who benefit from the secular resources are outsiders who got government permits as forests [SIC] users.”

The researchers concluded that, “unless social safeguards such as tenure rights of rural communities and benefit sharing between all actors are integrated in the mechanism,” the joint forest stewardship system efforts will fail.

Conclusion

The evolution of forest management strategies over the past century has led to the development of sustainable models for forest and environmental management practices that integrate scientific, folk/traditional, and indigenous knowledge systems. This development can occur in multiple ways.

The first, following the guidelines of the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to legally recognize and protect traditionally indigenous lands, territories, and resources, is to consult with the local indigenous communities to obtain their consent and approval for any development or exploitation of their lands, forests, and resources.

Beyond consultation and consent, the second principle is shared governance. Many nations have granted rights of governance of tribal or community forests, either fully or collaboratively, to the local indigenous groups. This requires both the consultation with and inclusion of indigenous groups in the development and execution of land management priorities and strategies.

Moving away from the management of forests on land traditionally held by indigenous groups, the final stage of integrating indigenous forest knowledge and scientific forestry principles would be for the knowledge gained through cooperative forest management in indigenous territories to become the basis for wider and more mainstream forest management principles in state and private forests alike.

Most of the experts whose work inform this article emphasize the need for effective decision and support tools that can foster the integration of indigenous forest knowledge at all steps of the process of sustainable forest management: inventorying, monitoring, planning, and management.

As these case studies have shown, indigenous forest knowledge can inform forest management practices in various ways, as Asselin summarizes40:

- by providing biological information and ecological insight

- as a source of alternative management practices

- by favoring biodiversity conservation

- by contributing to environmental monitoring and assessment

- as a support for social development

- as a source of environmental ethics principles

Based on research about the relatively healthier ecosystems found in forests under indigenous management, the result of instituting state and private forestry practices informed by indigenous forest knowledge should be an increase in biodiversity in terms of forest plant species composition as well as wildlife populations.

*References can be found here.