Insects

Your Grass-fed Burger isn’t Better for the Planet

For years, ranchers and some conservationists have argued that grass-fed beef is better for the planet than conventional cattle.

But a study published [March 2025] in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences challenges that idea, finding that cattle raised only on pastures do not have a smaller carbon footprint than feedlot cattle, which are quickly fattened on corn and other grains. This held even when the researchers took into account that healthy pastureland can help capture more carbon by pulling it out of the air and storing it in roots and other plant tissues.

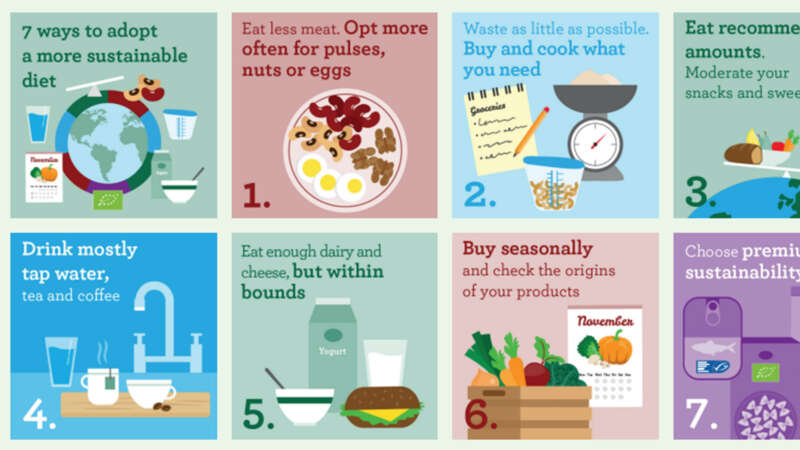

7 Steps to a More Sustainable Diet

Here are seven steps to a more sustainable diet.

Did you know that food production contributes about 21-37% of human-caused emissions?

To reduce your climate impact, eat more plant-based foods and reducing meat and dairy consumption, as these require fewer resources and produce fewer greenhouse gases.

Protecting Earth’s Lungs

Forests act as the planet’s terrestrial lungs. They provide us with fresh air, clean water, beautiful vistas and a sanctuary for countless wildlife.

But, today, more than ever, our forests are facing unprecedented threats from disease, climate change, mad-made destruction and harmful pests.

Join this documentary as it follows a group of professionals that developed, tested and formulated today’s forest health strategies to preserve the legacy of one of the planet’s most important resources – and to help us better understand and appreciate why we need to protect our forests.

This is a story that affects us all.

Our Broken Planet: How to heal our rainforests

Breathe in. Breathe out. The oxygen flowing through your body is the result of photosynthesis: the natural process through which living things convert sunlight into energy. About 30% of land-based photosynthesis happens in tropical rainforests. Rainforests are also great at sucking up excess carbon from the atmosphere – something we know we’ve got to do more of.

But in recent years, rainforests have been getting constricted: shrinking in size and choked up with smoke.

Listen to this podcast from the National History Museum to find out what’s going on and how we can help rainforests breathe deeply again.

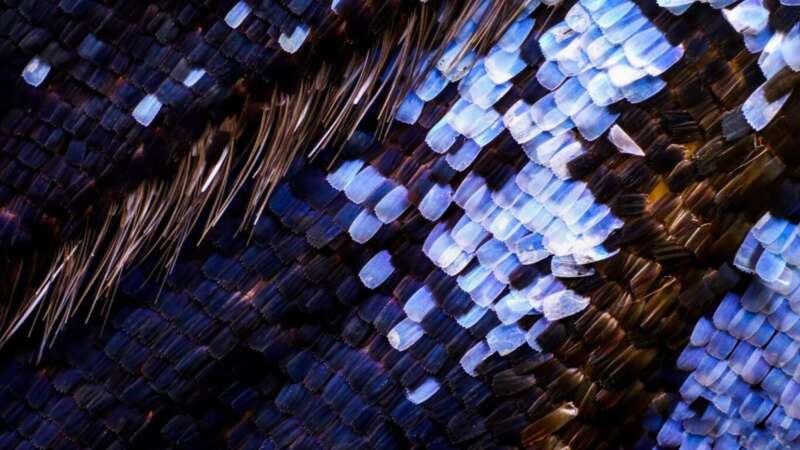

Chris Perani: The Art of Delicate Beauty

Chris Perani is a photographer who specializes in seeing the unseen. Known for his extreme macro photography, he captures butterfly wings and other minute natural subjects at a level of detail invisible to the naked eye. His images reveal dazzling mosaics of iridescent scales and textures that appear more like stained glass, sequins, or cosmic landscapes than fragments of an insect’s anatomy.

To overcome the razor-thin depth of field inherent in microscope lenses, Perani employs a meticulous stacking process. Using a 10× microscope objective mounted on a 200 mm lens, he shifts his camera forward in microscopic increments—sometimes as little as 3 microns per exposure. Each section of a wing might require 350 individual images, and a complete final work can demand more than 2,000 separate shots. These frames are then digitally merged into a seamless whole, revealing a complexity that even scientists rarely view in such clarity.

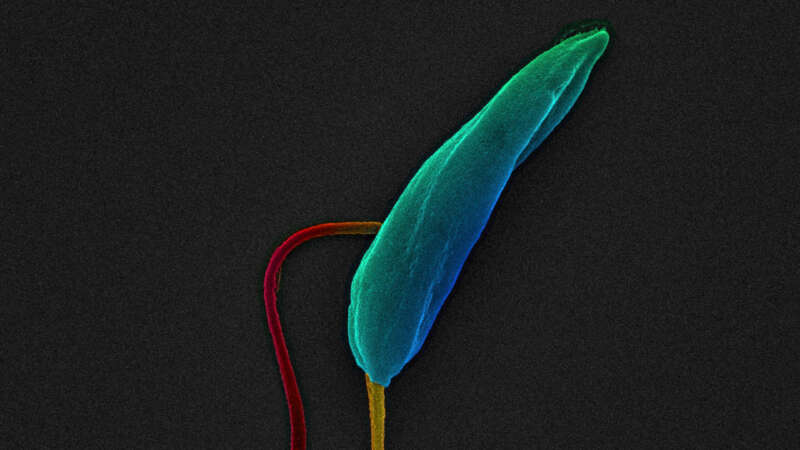

Dr. Gosia Domagalska: Outwitting Leishmania

In the quiet corridors of the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM) in Antwerp, Belgium, Dr. Malgorzata “Gosia” Domagalska is leading the fight against one of the world’s most neglected yet devastating diseases: leishmaniasis. As head of ITM’s newly established Unit of Experimental Parasitology, she has dedicated her career to understanding how parasites adapt, survive, and outwit medicine.

Domagalska’s path to parasitology was anything but straightforward. Trained as a geneticist, she earned her PhD in Plant Genetics at the Max Planck Institute in Cologne, followed by a Marie Curie Fellowship at the University of York. Early on, her research focused on plant development and hormones. But a shift came when she joined ITM in 2015: “This work is compelling not just scientifically, but socially,” she has said.

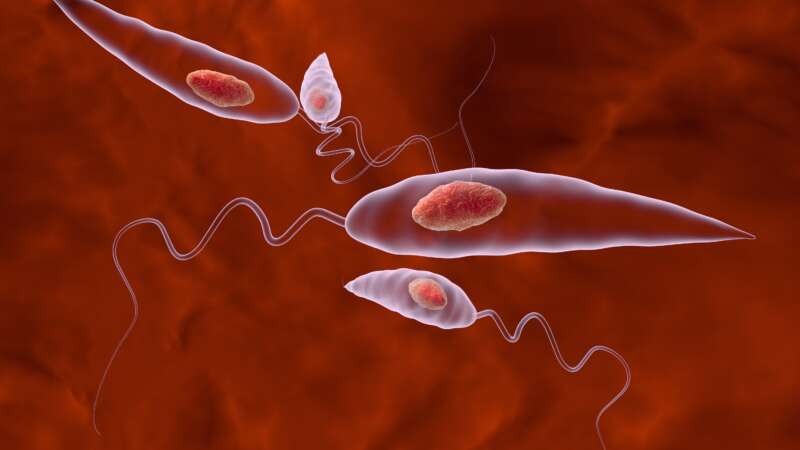

Leishmaniasis – Plain and Simple

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease that few people have heard of, but one you definitely don’t want to catch. Caused by Leishmania parasites and spread by the bite of female sand flies, it can silently linger in the body for years or surface in devastating ways, from painful skin sores to organ damage that can be fatal. The disease affects both humans and dogs, with our canine companions often acting as unwitting reservoirs that keep the infection circulating.

As climate change expands the habitat of sand flies into new regions, the threat of leishmaniasis continues to grow. With no reliable cure and limited vaccine options, prevention is key. Protecting yourself and your pets with repellents, protective gear, and vigilance is the most effective way to guard against this serious but often overlooked disease.

Sand Flies: The Silent Biters Spreading A Deadly Disease

Phlebotomine sand flies are notorious biters. They not only cause great irritation but are also capable of spreading a deadly disease – visceral leishmaniasis.

While the World Health Organization states that currently 1 billion people live in areas endemic for leishmaniasis and at risk of contracting the disease, a recent study using a statistical model, predicted that visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is undergoing geographic expansion and 5.3 billion people could be at risk of acquiring the disease in the future.

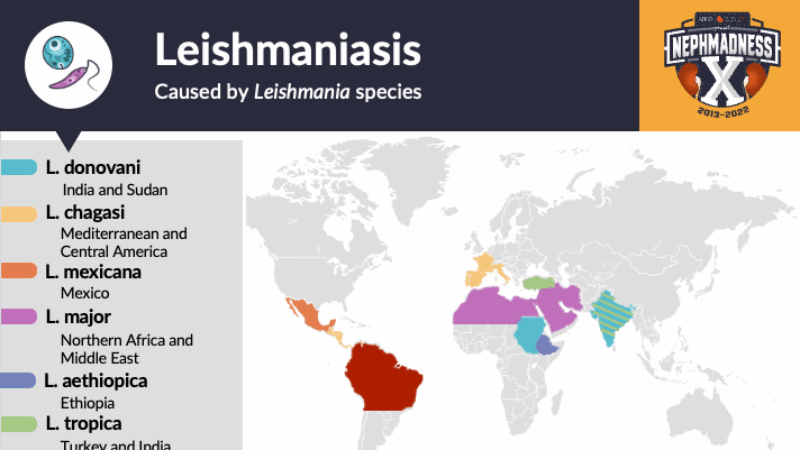

Leishmaniasis currently occurs in approximately 90 countries. These countries are located in the warmer climates where sand flies thrive: in the tropics, subtropics, and in Southern Europe. Climate change and other variations in the environment have the potential to expand the geographical range of where sand flies can live and therefore where the disease can infiltrate the human population.

Epidemiology of Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease spread by the bite of infected female sandflies. It can affect the skin, mucous membranes, or internal organs. The most serious form, visceral leishmaniasis (VL), damages the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and kidneys, and is caused mainly by Leishmania donovani and Leishmania infantum.

Every year, 1–2 million people are affected, with over 90% of cases concentrated in just 13 countries. While many infections show no symptoms, untreated VL is usually fatal. Malnutrition, HIV co-infection, genetics, and young age (especially under 5) increase the risk of severe disease.

Dr. Mark Finney: Changing How We Fight (and live with) Fire

Dr. Mark Finney is a Senior Scientist and Research Forester with the U.S. Forest Service at the Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory. With a Ph.D. in wildland fire science from UC Berkeley, Finney has spent decades exploring fire as both an ecological force and a physical process. His work has laid the foundation for many of the wildfire behavior models used today across the country.

Finney is a strong advocate for rethinking traditional fire suppression strategies. He emphasizes the need to let “good fire” play its role in the landscape, using tools like prescribed burns and targeted fuel treatments to prevent more extreme fires down the line. His research has revealed that long-held beliefs about how fires spread, such as the role of radiant heat, are often incorrect.