Insects

The Drone Edge in Vector Control

Achieving global vector control’s potential requires “realigning programs to optimize the delivery of interventions that are tailored to the local context [and]…strengthened monitoring systems and novel interventions with proven effectiveness.” This includes “integration of non-chemical and chemical vector control methods [and] evidence-based decision making guided by operational research and entomological and epidemiological surveillance and evaluation.”

Drones or “unmanned aerial vehicles” (UAVs) can save time and money compared to conventional ground-based surveys. Sophisticated models and monitoring equipment can be purchased for a few thousand dollars. They don’t require a pilot’s license, they are becoming easier to fly, and their paths can be fully automated through AI, machine learning, global positioning systems, and computer vision.

Mosquito Control Drone Application

Check out this video from Calcasieu Parish Mosquito and Rodent Control on how they are using drone technology to spray in hard to reach areas and increase the efficiency of eliminating disease-carrying populations of mosquitos.

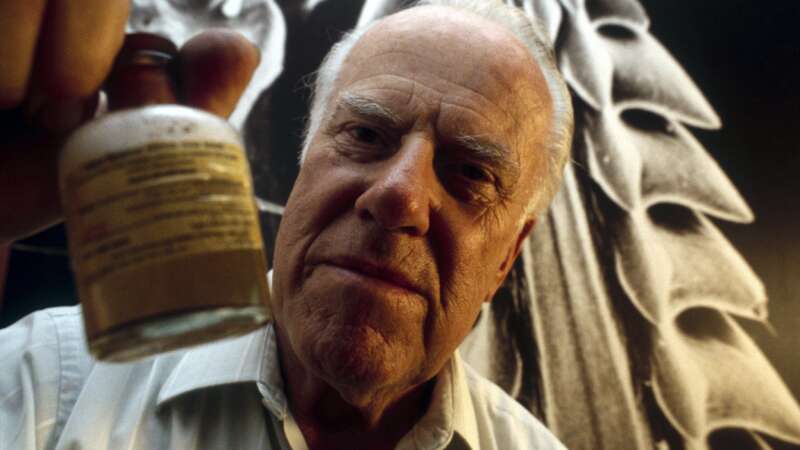

Jacques Régnière: Budworm to BioSIM

Jacques Régnière, born in Quebec City, has dedicated over four decades to advancing our understanding of forest pests and protecting our global forests. Earning his bachelor’s degree in biology from Laval University and a Ph.D. in insect ecology and biomathematics from North Carolina State University, Régnière began his career at the Canadian Forest Service in 1980, where he served until his retirement in 2024.

Throughout his distinguished career, Régnière focused on pressing issues in forest ecology, notably the population dynamics of the spruce budworm, mountain pine beetle, and spongy moth. His work in quantitative ecology has influenced pest management practices and provided a better understanding of climate change’s impact on invasive species and forest health.

Dr. Willy Burgdorfer: One Tick at a Time

Dr. Willy Burgdorfer, born on June 27, 1925, in Basel, Switzerland, is known for transforming the understanding of tick-borne illnesses.

Burgdorfer pursued his undergraduate and doctoral studies in parasitology and tropical bacteriology at the University of Basel – where he first developed his fascination with ticks while studying how these arthropods transmitted spirochetes that caused relapsing fever. In 1951, Burgdorfer moved to the United States for a fellowship in Montana at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) – a National Institute of Health biomedical research facility for vector-borne diseases, such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Lyme disease and Q fever.

What Does Lyme Disease Do to Your Body?

What exactly is the connection between a tick bite and lyme disease?

While we’re not sure exactly where and when the disease originated, we do know a lot about how it works, its signs, its symptoms in humans and dogs, how it’s spread and its treatment.

Check out this video by Seeker to learn all about what lyme disease does to your body.

Tick-ing Time Bomb: The Expanding Threat of Tick-Borne Diseases

Urbanization, resistance to pesticides, and, most critically, climate change are creating ideal conditions for global tick proliferation. As these 8-legged bloodsuckers expand their territories, the world should expect a corresponding rise in Lyme disease, spotted fever, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, tick-borne encephalitis, and other conditions that infect humans, pets, and livestock.

“This is an epidemic in slow motion,” a Centers for Disease Control (CDC) tick expert and research, biologist told the Associated Press.

Ticks live on every continent except Antarctica, and while estimates of annual tick populations vary, the scientific community agrees that their numbers are growing. Researchers also are unanimous that arachnids pose an increasing health risk as mild winters and longer summers associated with global warming kill off fewer individuals, give them longer to develop and feed, and make higher elevations and northerly latitudes that previously were too intemperate or elevated more hospitable.

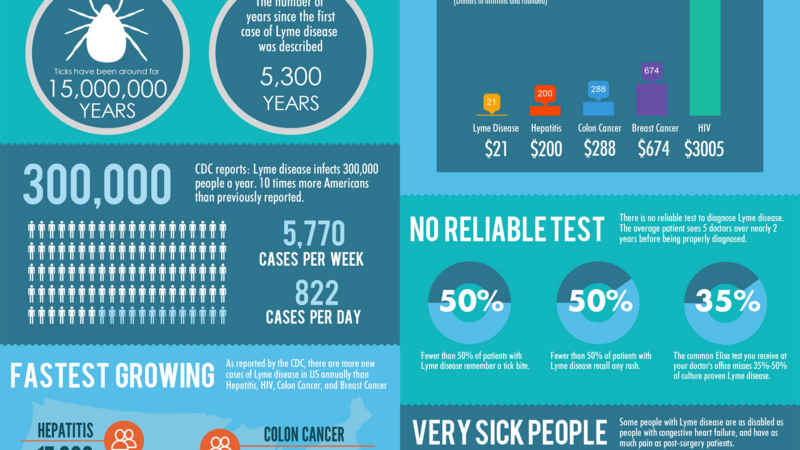

Lyme Disease Quick Facts

Lyme disease is one of the fastest growing infectious diseases in the country and one of the most difficult to diagnose. Experts in the medical and scientific community, as well as key legislators, have deemed Lyme disease an epidemic … a national public health crisis … and a growing threat.

300,000 people are infected with Lyme disease each yearAt least 300,000 people are infected with Lyme disease each year

New tick-borne diseases are emerging … the number of tick endemic regions is growing … the tick population is increasing … and, the number of people infected with Lyme disease is steadily rising.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that at least 300,000 people are infected with Lyme disease each year in the United States. That’s 25,000 new cases per month. Twenty-five percent of those patients are children, ages 5 to 14.

Information and Infographic obtained from https://danielcameronmd.com/.

Shiuly Khatun: Dengue Warrior

Shiuly Khatun is a Field Supervisor at the Dhalpur Aalo Clinic in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where she manages and coordinates the clinic’s operations. Her daily responsibilities are vast and critical, ranging from mapping areas and dividing work for community volunteers to conducting health sessions and overseeing satellite clinic activities.

Dengue fever, once confined to the tropics, now threatens the U.S.

Climate change is expanding the habitat of the mosquitoes that carry the disease, allowing them to spread further north.

Meg Norris was traveling in Argentina in April when the first signs of dengue fever hit her. The weather in Salta, just south of the Bolivian border, was warm, but Norris, a 33-year-old from Boulder, Colorado, zipped a fleece sweatshirt around her body to stop herself from shivering.

“I thought it was sun poisoning,” she said.

Dengue Explained in Five Minutes

Check out this video by Free Med Education to learn about dengue fever, its cause, and its symptoms.